03The impact of migration on Birmingham’s skills base

The previous section gives us a static picture of skills levels in Birmingham. But the population of a place and its characteristics are always changing as a result of the migration flows that can alter the skills base of a city over time. This means that upskilling the current population is only one way to address the skills issue. Another is to improve the ability of the city to retain skilled workers and attract them from other parts of the country and this is what this section looks at.

This section combines migration data from the ONS and the Census to look at migration to and from Birmingham to understand what impact it has on the skills profile of the city.

Birmingham experienced a net outflow of people in recent years

Between 2009 and 2015, around 361,100 people moved into Birmingham from the rest of England and Wales and approximately 411,100 people moved out. This resulted into a net outflow of around 50,000 people from the city. In comparison, Bournemouth experienced the net largest net inflow of 15,100 people and London the largest net outflow of 340,300 people.

Most of this migration flow was between Birmingham and the rest of the West Midlands: 28 per cent came from the West Midlands and 34 per cent of those of who moved out remained in the region. This resulted in a net outflow to the rest of the region as shown in Figure 10.

Figure 10: Net regional migration to Birmingham, 2009-2015

On a city basis, Birmingham saw its two largest net inflows from Coventry and Bradford while the largest net outflow was to Telford. This suggests that most of the movements were between Birmingham and its neighbouring cities. There was also a large net outflow to London.

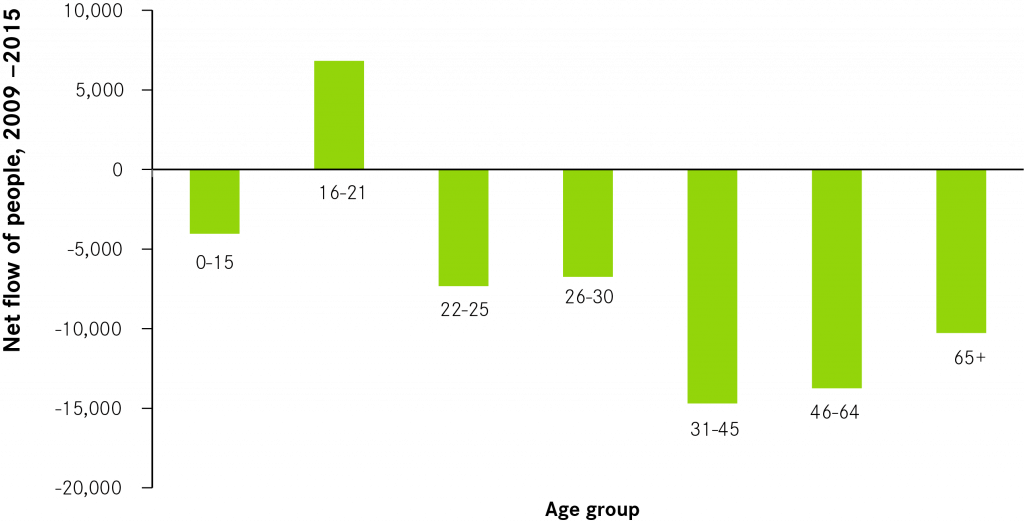

Breaking this down by age shows that Birmingham experienced a large net inflow of 16 to 21 year- olds (see Figure 11). For this age group, the net inflow was 6,830 people. But it saw a net outflow for every other age group.

Figure 11: Net flow of people by age groups, 2009-2015

Birmingham lost degree holders

While ONS data on migration does not give information on the qualifications of migrants, the 2011 Census provides us with this information for movers between 2010 and 2011. Splitting the data into three age groups — 16 to 21, 22 to 30 and 31 to 45 — reveals three important trends, as shown in Figure 12.

Firstly, Birmingham gained people in the 16–21 age group with A-level qualifications. This was mainly driven by a new inflow from the Greater South East with London being the main contributor to this gain. In contrast, there was an outflow of people with the same level of qualification to the Midlands and the other regions to the North of Birmingham.

Secondly, the city saw a net outflow of degree holders aged 22 to 30. The movement of the people in this age group perfectly mirrors the 16—21 group. The largest outflow of degree holders was to the Greater South East, with London being the biggest gainer. In contrast, Birmingham gained degree holders from all the other regions with the exception of the South West.

Thirdly, there was an also an outflow of degree holders aged 31 to 45. However, the geography of this net outflow was different from that of the younger degree holders, with the largest number of people leaving Birmingham but remaining within the West Midlands.

Using the wider migration data for 2009 and 2015, which allows us to look at the movement between local authorities, shows that the majority of these 31 to 45-year-olds did not go very far; on a net basis, Bromsgrove was the authority that Birmingham lost most people to, followed by South Staffordshire. This means that these movers remained very much within commutable distance to Birmingham, even if they no longer lived there. There was also a very small net inflow of older graduates from London back to the city.

Figure 12: Net flow by qualification, age groups and regions, 2010/11

Box 3: Migrant population in Birmingham

International migration can also play an important role in improving the skills level of a place, particularly in large places like Birmingham where in 2016 18 per cent of the resident population was non-UK born.

Using data from the 2011 Census shows that the skills profile of foreign-born residents in Birmingham was more polarized than the UK-born one: in 2011 foreign-born residents were more likely to have no qualifications (34.8 per cent) but also more likely to be degree holders (22 per cent) than the UK-born population — this was 28.9 and 20.7 per cent respectively. But there were variations within the foreign-born population. When looking just at EU-born residents in Birmingham, they are less likely to have no qualifications (19.4 per cent) and more likely to have a degree (23.5 per cent) than the UK-born population. This suggests that Brexit and potential changes to migration policy might make the skills issue more acute.

Looking at the occupation of EU workers living in the city shows that almost half of EU migrants in 2011 were in low-skilled jobs. This suggests, reflecting the national picture, that there are barriers for to accessing jobs for this group of people.

Summary

As a result of these movements, Birmingham experienced a net outflow of people from the city between 2009 and 2015. Breaking these flows by age and qualifications shows:

- There was a large net inflow of 16 to 21-year-olds. Many of these are likely to have been A-level holders moving to the city to attend university.

- The city experienced a large net outflow of young people with a degree and this was driven by graduates moving to London.

- There was also a net outflow of older degree holders but the majority remained within commutable distance of the city.

The net inflow of university students and the net outflow of degree holders suggest that an important element in closing the skills gap will be to make the most of a new generation of graduates and this is what the next sections look at.