04Does the education system develop interpersonal and analytical skills ?

To ensure people and businesses are able to adapt to the changing economy, it is crucial that people are equipped with analytical and interpersonal skills through education and training.

Yet there is no common framework for interpersonal and analytical skills. The language and definitions used to describe these skills often varies, with references to ‘employability’, ‘soft’, ‘vital’ and ‘transferable’ skills, among others. This results in a lack of clear understanding of what skills individuals need to succeed in the labour market and poses three challenges. Firstly, interpersonal and analytical skills are likely to be undervalued. Secondly, it makes developing these skills harder. And thirdly, it is difficult to measure progress on the development of analytical and interpersonal skills.

With these challenges in mind, this section looks at how the supply of interpersonal and analytical skills varies across cities at different stages, from early years to lifelong learning.7 It also sets out a number of recommendations on how policy makers might help improve outcomes at each stage.

Preparing younger generations for the labour market – the early years

The development of analytical and interpersonal skills begins very early in life, and early years education has an impact on the ability to learn and achieve over the longer term.8 For this reason, intervention at this point is crucial in ensuring every child can develop the skills needed to fulfill their potential.

Reflecting the importance of early years, the Government has put greater emphasis on this policy area. Early years interventions played a central role in the Government’s social mobility strategy,9 and interpersonal and analytical skills sit at the core of the new Early Years Foundation Stage (EYFS) framework. The EYFS came into effect in 2017. It outlines standards for learning and development for children from birth to five years old and has a strong emphasis on communication and language, physical development and personal, social and emotional development.10

However, achievement in early years varies across the country and is lower in cities in the North and Midlands. On average, 69 per cent of children in England achieved or exceeded the expected standards in the early years, but there is significant variation between cities (see Figure 8). York has the highest share of children achieving expected standards in all areas. Yet, York is an exception among cities in the North, as the other cities in the top ten are in the Greater South East. Indeed, in cities such as Aldershot, Bournemouth, Milton Keynes and Reading, more than 70 per cent of children achieved expected standards. In contrast, only 60 per cent of children in Peterborough, Hull and Burnley met all of the 17 learning goals.

Past experience suggests that gaps in the early years are likely to persist, if not widen, in school and into adulthood. To prevent this, national and local policy makers should work together to ensure every pupil receives excellent early years education, where children can start developing interpersonal and analytical skills. In particular, cities should focus on two actions:

1. Improve uptake of early years education

Given how important the early years are for outcomes later in life, it is essential that every child receives high-quality early years education. It is vital that the Government raises the quality of early years education through workforce development, and ensures that the current set of entitlements supports equal access to this provision. As part of this, cities can play a role in improving the take-up of early years provision.

The Government currently offers free early years education to all two-year-olds from disadvantaged backgrounds, alongside other entitlements and benefits, yet take-up is patchy and families are not always aware of this support. Local authorities should use the data they hold and the connections they have with organisations involved in the early years to identify children that could benefit from the scheme and drive take-up up of early years provision in their cities. For example, the London Borough of Islington is working with local stakeholders to identify children with special needs in order to provide additional support in the early years (see case study 1).

Case study 1: Islington council – using data to identify the needs of children

To identify children in need of additional support in the early years, the London Borough of Islington established an Early Years and Disability Funding Panel.

The panel helps to build capacity by using data from education, health and social care services to identify children who have special needs. This, in turn, improves the timeliness and quality of support. The council holds meetings every term with education providers, social care services and other stakeholders and, prior to the meeting, organises the data from different organisations in a single data sheet for discussion. This enables the council to track individual children and families over time.

With the new system, early years providers have been able to build profiles on the children they are working with. This has led to increased utilisation of data across providers, which in turn has improved decision-making, integrated working, and enabled collaboration and coordination of staff working in different professional disciplines, with consequent benefits

for children.

2. Work closely with organisations focused on the early years and families to promote and share best practice

Organisations such as the Early Intervention Foundation (EIF) and the Education Endowment Foundation (EEF) have established a growing body of evidence on what works to improve outcomes in the early years.12 In their research, they found that improving communication and language in the early years, as well as self-regulation skills, improve educational attainment later in life. Furthermore, as this research shows, these skills are among the most in demand from employers and will likely become even more important in the future.

Cities should help facilitate the sharing of best practice and testing of new approaches. This work should focus on interventions that have already been found to have a positive impact on the early years, such as family skills interventions and vocabulary learning. While cities are taking an active role in this space (see case study 2, for example), more can be done.

Case study 2: EasyPeasy Bournemouth – finding ways to experiment with new ideas and act as a test bed

To improve children’s skills through family learning, Bournemouth Borough Council has been working in partnership with the Sutton Trust and the Esmée Fairbairn Foundation to introduce EasyPeasy, a smartphone app for parents of pre-school aged children.

The app, which sends game ideas to parents combined with information on child development, was first prototyped in 2014 and then piloted in Bournemouth in partnership with the Council. It is designed to encourage positive habits within families both in terms of play and interaction and games were developed in consultation with experts to ensure its efficacy. The app covers all of the EYFS areas of learning and development, sending tailored prompts, encouragement and reminders to parents.

The Bournemouth trial was rigorously evaluated by researchers at the University of Oxford and was found to have a positive effect on families after 18 weeks. Children made progress in terms of social and emotional development. Furthermore, the app had positive effects on parents’ engagement and confidence in setting rules and sticking to boundaries. Given its success, the app is now used in a number of other local authorities, including Newham and Camden in London, Doncaster and Coventry.

Preparing younger generations for the labour market – schools and colleges

If policy interventions in the early years are tailored to the development of soft skills together with literacy and numeracy, the focus starts to shift towards curriculum and subject/cognitive knowledge development when pupils enter school. Analytical and interpersonal skills are not necessarily skills that can be taught directly but developed through exposure to a rich curriculum, particular ways of teaching and extra-curricular activities.

Good literacy and numeracy skills (as measured through attainment in Maths and English at GCSE level) are intrinsically important to progression in education and are positively correlated with the broader development of analytical and interpersonal skills.

The development of analytical and interpersonal skills also occurs outside the classroom. Extra-curricular activities are thought to be a good complement for what happens in the classroom and activities, such as debating or team sports, offer an opportunity to young people to apply skills, such as negotiation and team working, in real life situations.15 Schools recognise the importance of extra-curricular activities and 97 per cent of them indicated extra-curricular activities as their preferred way to develop soft skills. In particular, these activities included arts clubs (91 per cent), outward bound activities (72 per cent), hobby clubs (71 per cent) and subject learning clubs (60 per cent).16

For these reasons, GCSE attainment and take-up of extra-curricular activities reveal important insights into the development of analytical and interpersonal skills among children.

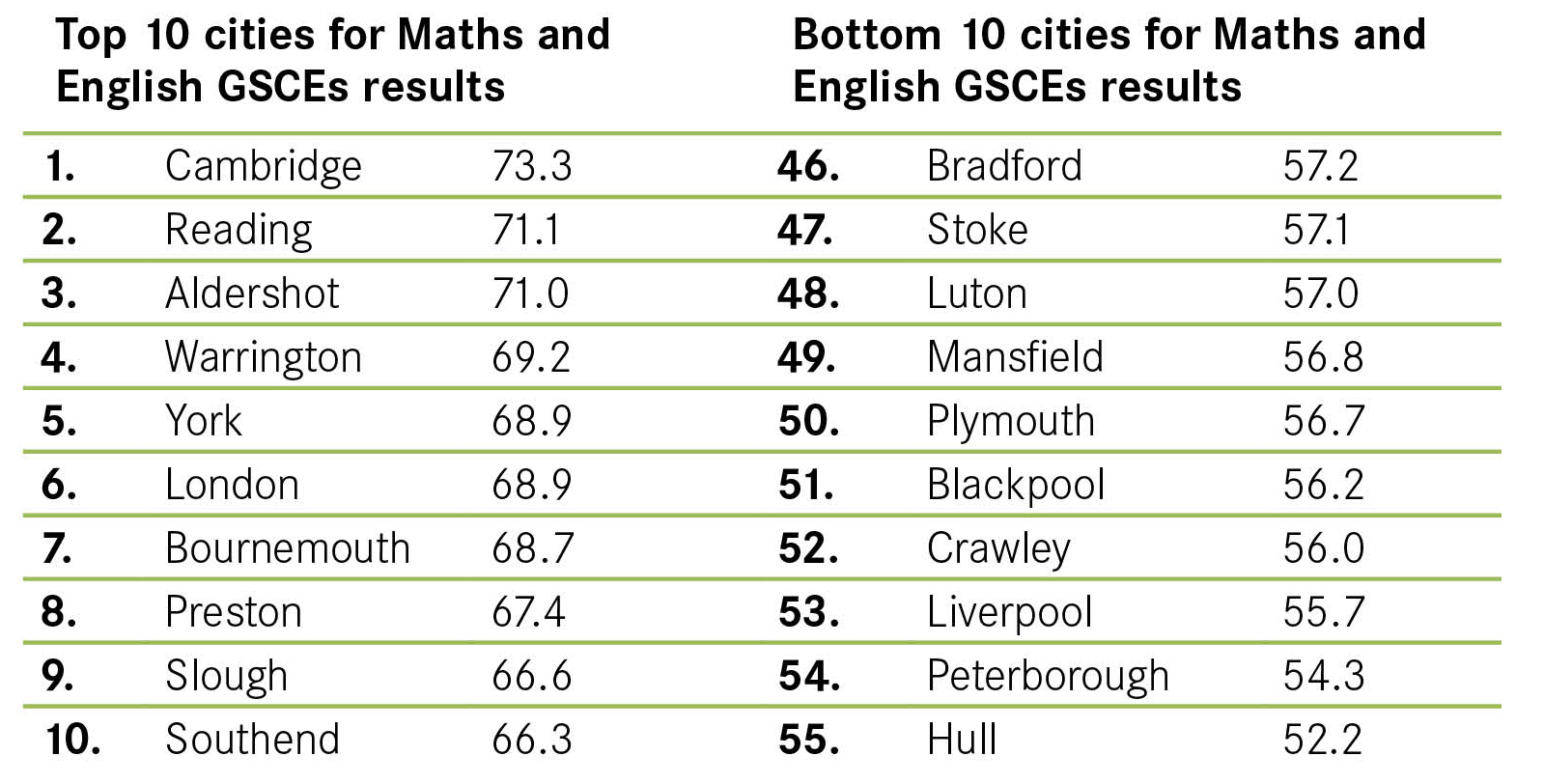

Firstly, attainment in Maths and English at GCSE level is lower in northern and midlands cities compared to cities in the Greater South East. In 2017, over 70 per cent of pupils in Cambridge, Reading and Aldershot achieved 9-4 grades in Maths and English against a national average of 64.2 per cent. These cities also had a higher share of pupils achieving a ‘strong pass’ (9-5 grades) compared to the national average of 42.9 per cent. In contrast, Hull, Stoke and Blackpool had among the lowest share of pupils achieving 9-4 pass, and only one in three achieving a ‘strong pass’ in Maths and English

(see Figure 9).

Figure 9: GCSEs 9-4 achievements in Maths and English across English cities, 2016 (%)

In terms of extra-curricular activities and work experience, the picture looks similar with pupils in the Greater South East more likely to participate than those in cities in the North and Midlands. Research by the Sutton Trust found that 37 per cent of young people do not take part in any extra-curricular activities, while this rises to more than half (54 per cent) among pupils from disadvantaged backgrounds.15 While there is a lack of data on participation in extra-curricular activities at the local level, the geography of pupils from disadvantaged backgrounds provides some indication of how participation is likely to vary. In terms of extra-curricular activities and work experience, the picture looks similar with pupils in the Greater South East more likely to participate than those in cities in the North and Midlands. Research by the Sutton Trust found that 37 per cent of young people do not take part in any extra-curricular activities, while this rises to more than half (54 per cent) among pupils from disadvantaged backgrounds. While there is a lack of data on participation in extra-curricular activities at the local level, the geography of pupils from disadvantaged backgrounds provides some indication of how participation is likely to vary.

Liverpool, Hull and Birmingham are the cities with the highest share (more than 20 per cent) of pupils from disadvantaged backgrounds (as measured by the number of pupils eligible for free school meals). In contrast, in Aldershot, Bournemouth and York less than 10 per cent of pupils are eligible for free school meals. Given the lower likelihood of pupils from disadvantaged backgrounds participating in extra-curricular activities, it is likely that overall levels of participation are lower in the former group of cities compared to the latter.

Work experience also has the potential to endow children with the interpersonal and analytical skills employers need. Although no longer compulsory, a recent survey by the Government found that the majority of schools and colleges offer work-related experience to all students (in year 10-11 or in year 12-13) and that schools and colleges perceived work-experience as a way to improve children’s employability skills such as communication and interpersonal skills.

Despite this positive evidence, however, take-up varies from school to school. From the little data available, it appears that the majority of employers offering these opportunities are predominantly found in the South East.18

Taken together, this data suggests that pupils in less economically successful cities have fewer opportunities to develop strong analytical and interpersonal skills. As face-to-face interaction, negotiation and complex problem solving become more important in work, young people in these city economies are likely to be less well equipped to access opportunities in the future labour market. This means that existing divides between cities are likely to widen.

National and local policy-makers should work together to improve take-up and quality of education in schools and colleges. In particular:

- The Government should continue to improve numeracy and literacy

While there have been significant improvements in the attainment of GSCE Maths and English at the national level, there are still large gaps in attainment between cities and too many young people are leaving school without having developed good literacy and numeracy skills. Maths and English are the foundation for the broader development of interpersonal and analytical skills and as such, more needs to be done to improve attainment in these subjects. Given that the quality of teaching is one of the most important determinants of pupil attainment, the Government should focus on improving teacher retention and development, particularly in cities with the lowest attainment rates.

2. The Government should ensure that all young people have access to extra-curricular activities

Up until 2017, schools used to receive funds from the Government to ‘build character’ through the Character Grant Scheme. However, the scheme was scrapped and the grant has been substituted by the Essential Life Skills initiative which aims to increase take-up of extra-curricular activities but is restricted to Opportunities Areas only.19 This is good news for Opportunities Areas, as they are the most in need of intervention, but developing these skills is essential for every pupil across the country and the Government should ensure that every child has access to activities that help support their development.

3. Cities should establish Skills Compacts to promote collective responsibility and action for improving education and training.

Local authorities and local skills bodies should play a convening role and encourage stakeholders to sign up to a Skills Compact. Similar to the Boston model in the US (see case study 3), local authorities should coordinate activity in their cities, facilitating collaboration between schools and other stakeholders. To measure progress, every Compact should set measurable targets based on the specific goals of the compact.

Through the Skills Compact, cities should act on two fronts. Firstly, the Skills Compact should focus on promoting the use and sharing of best practice. As part of this, local authorities should support schools and local organisations to pilot different initiatives to improve analytical and interpersonal skills, monitor and evaluate their outcomes and promote the dissemination of the learning experience from these pilots.

Secondly, the Skills Compact should target children from disadvantaged backgrounds to ensure they can develop interpersonal and analytical skills. Practically this would firstly require the identification of barriers to participation and attainment. There may be a series of relatively cost-effective interventions that help to address these barriers: the creation of an easy-to-access platform, with all the information with regard to extra-curricular activities and other skills development activities that families and children can access, may help to raise awareness of existing provision, for example.

This work is already underway in some cities, such as Liverpool (see case study 4). Yet, given the scale and urgency of the challenge, it is imperative for every local authority to take concerted action.

Case study 3: The Boston Compact – using local leadership to make provision of skills more efficient

In 2011, the Boston mayor, Boston School Committee Chair, the Boston Public Schools attendant and leaders from the Boston Alliance of Charters Schools signed a formal ‘Compact’ to improve the quality of education in

the city.

Under the leadership of the mayor, the Compact set out cross-sectoral professional strategies, a common accountability system with a common framework, and better use of city facilities. Through better coordination, learning and sharing of best practice, the Compact has introduced a Boston Schools Hub website to highlight options available for families in the city. It is also focusing on practice related to effective teaching and learning, especially for individuals with special needs and English learners.

The Compact has expanded over the years and now covers more than 93 per cent of all students in the city. In the English Language Learner Initiative, participants reported benefiting from practical strategies and professional development, and changes in classrooms which included increased linguistic focus and student’s interactions.

Case study 4: School improvement Liverpool – creating a common framework to improve education

School Improvement Liverpool was established in 2014 to offer support to nurseries and schools to ensure children and young people have the opportunity to develop, learn and excel in life. Its services and its structure resemble the Boston Compact.

School Improvement Liverpool offers a range of support services such as training, consultancy, qualifications and in-school support. The main partners include Liverpool City Council, Liverpool Learning Partnership and the Liverpool School Business Managers Association. Through coordination and sharing of best practice, it offers services for the early years, primary and secondary schools. For example, School Improvement Liverpool provides support and training for the Philosophy for Children project, which aims to help children become more willing and able to question, reason, construct arguments and collaborate with others. The project, which already runs in 25 schools in Liverpool, is highlighted as one of the most promising by the Education Endowment Foundation.

To date, School Improvement Liverpool has worked with over 900 schools and businesses offering services to over 170,000 children and young people and supporting over 18,000 professionals.

Ensuring the existing workforce is able to adapt to changes in skills demand – adult learning

Early intervention is crucial in order to close the attainment gap among pupils across the country, but this does not preclude the necessity of lifelong learning and adult education.24 With two-thirds of the 2030 workforce having already been through compulsory education, it is vital that adults also have the opportunity to develop their skills.25 Yet as people get older, the emphasis on the development of analytical and interpersonal skills tends to fade away. As a consequence, not enough is done to improve the skills of the current workforce.

Too many adults lack basic literacy and numeracy skills, particularly in parts of the North.26 In 2011, 15 per cent of the workforce lacked basic literacy skills, while 24 per cent lacked basic numeracy skills. In the North East, numbers were even higher with 17 per cent of the workforce lacking literacy skills and 31 per cent lacking numeracy skills. London also had a high share of individuals with poor literacy and numeracy, due to the polarised nature of its labour market, but its situation is improving compared to 2003 thanks to interventions in schools.27 Levels of poor literacy and numeracy are far lower in parts of the South: the South East and South West are the best performing regions with less than 10 per cent of the workforce lacking basic literacy skills and less than 20 per cent lacking numeracy skills.

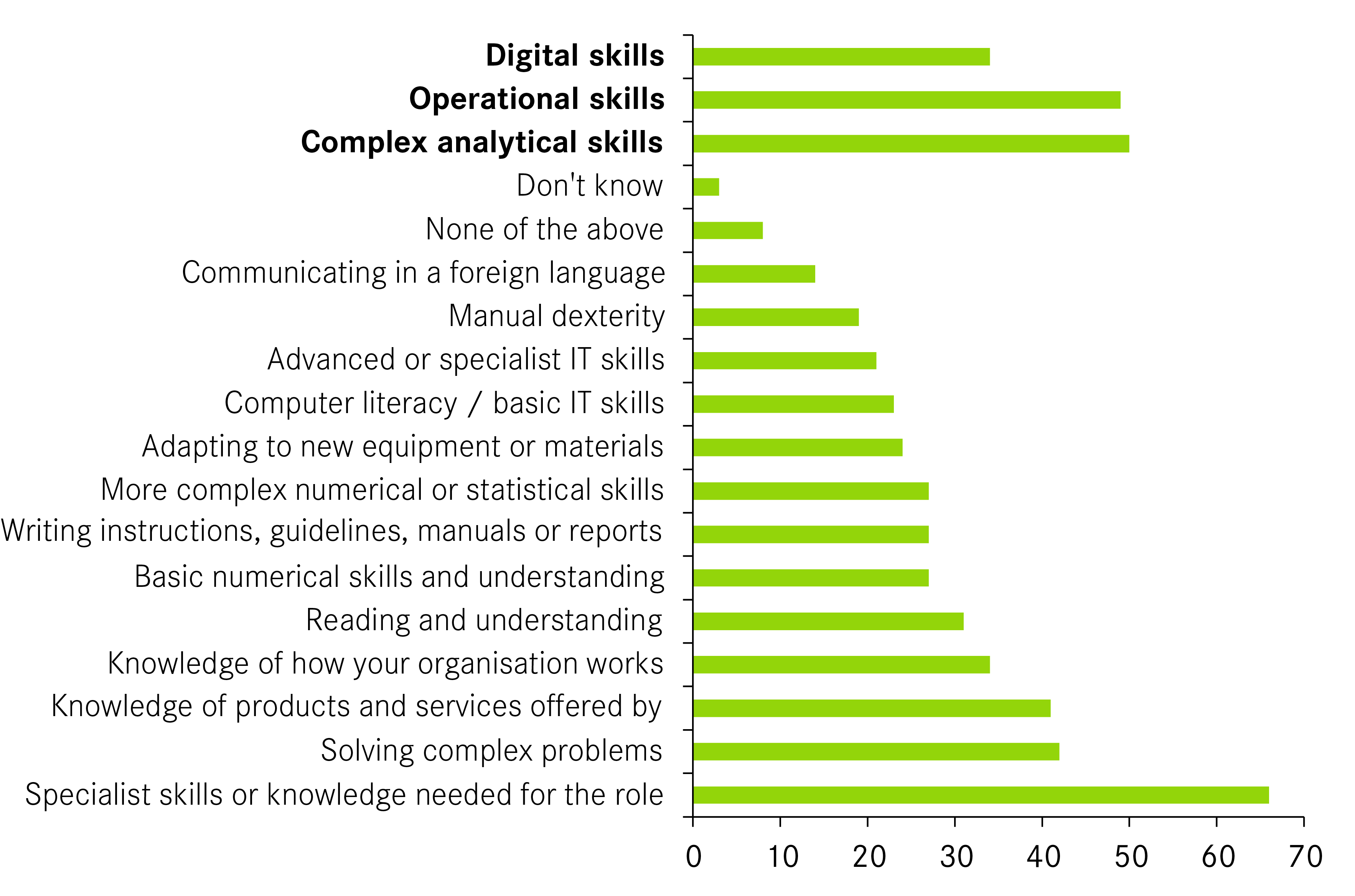

According to the Employer Skills Survey (2017), the main reason employers find vacancies hard to fill is lack of skills, particularly complex analytical skills. While two-thirds of employers with skills shortages stated that applicants lack the specialist skills or knowledge for the role, among more transferable skills one in every two employers in the UK found complex analytical skills to be the most difficult skills to obtain from applicants alongside managerial and customer handling skills.

Within analytical skills, employers are most likely to cite problem-solving (42 per cent) and numerical skills (27 per cent) as the hardest to find among applicants (see Figure 10). The survey suggests that finding applicants with complex analytical skills is a challenge for businesses across the country, in particular in the North and Midlands. In these regions, the share of employers struggling to find applicants with complex analytical skills is higher than the national average.

Figure 10: Technical and practical skills found hard to obtain among applicants, 2017

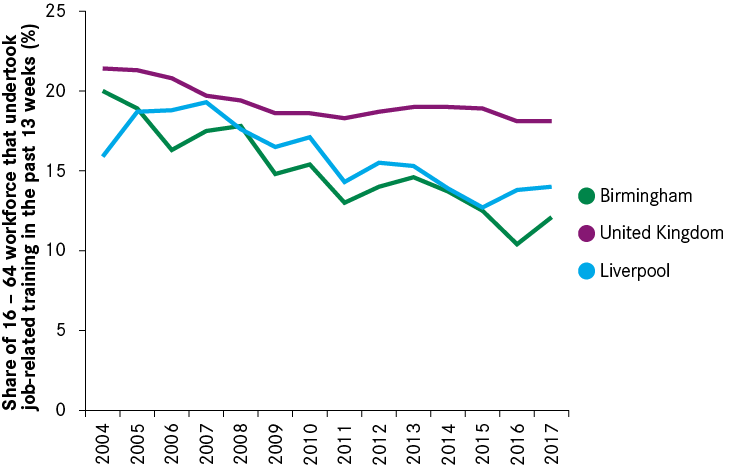

Despite the clear need for lifelong learning, numbers undertaking job-related training are down, particularly in cities where the likelihood of workers undertaking training was already lower than average. These falls are mirrored in other forms of lifelong learning, including apprenticeships and participation in further education. Furthermore, not only has the number of individuals undertaking training been declining, but it has become increasingly skewed towards individuals from more affluent socio-economic backgrounds who tend to already have higher skills.

Between 2004 and 2017, the share of workers undertaking job-related training in England fell by 14.5 per cent. This trend holds among the majority of cities, with 42 of them having seen a decline in job-related training and only 13 having seen

an increase.

In addition, the decline in job-related training has been sharpest in those places that stand to benefit the most from up-skilling and re-training. For example, the share of workers in Liverpool and Birmingham undertaking on the job training was already relatively lower in 2004 (19 per cent in both compared to national average of 21 per cent) and it declined more sharply compared to other areas. The share of workers undertaking on-the-job training has declined by 25 per cent in Liverpool and by 35 per cent in Birmingham (see Figure 11).

Figure 11: Share of 16 – 64 workforce undertaking job-related training in the past 13 weeks, 2004 – 2017

1. The Government should take a cross-departmental approach to raising investment and participation in lifelong learning, supported by a new What Works Centre for Adult Education.

As the nature of jobs continues to evolve and people work for longer, it is crucial to ensure that individuals that have already left compulsory education can up-skill and retrain. Government departments need to work together to raise awareness of opportunities and remove barriers to them, including financial ones. To be effective it is essential that this builds on lessons from the past and is supported by evidence on what works. However, there is currently a much richer understanding of what works to improve educational attainment among children and young people. It is now time to raise the profile of adult education and create a similar organisation that focuses on lifelong learning.

2. Local authorities should pilot new flexible methods of the provision in adult education

From 2019/20, combined authorities will have control over the Adult Education Budget. This is an opportunity for cities to ensure that provision is tailored to the needs of local communities and businesses and to pilot new approaches.

One of the challenges related to the take-up of adult education is the necessity to juggle training between work and other personal commitments, such as family and care. Local authorities should first work to identify barriers to take-up of adult education in their local areas. Secondly, local authorities should use their powers to experiment with different forms of provision, such as evening classes or online courses, to widen access and participation in training. Properly evaluated, this would help to identify the most effective ways to improve adult education.

3. Improve the take-up of adult education through better coordination with local stakeholders

Local authorities should also use the Skills Compact model outlined in the schools section to improve take-up and quality of provision for adult education. Building on work already underway, this means working collaboratively with further education colleges and other local stakeholders, learning and sharing from experimentation with different pilots, and raising awareness among individuals about the opportunities available in the city. (See case study 5).

Case study 5: Step Up – supporting low-paid workers to progress their careers

Building on collaboration between the Learning and Work Institute, Trust for London and the Walcot Foundation, the Step Up initiative was launched in 2015 to help low-paid workers progress in their careers and move into

better work.

Key features in the delivery of the programme involved a personalised approach, one-to-one support, and coaching to boost participants’ motivation and confidence. The initiative also involved partnerships with training providers and organisations connected to employers. Businesses were crucial for the initiative and were engaged in a number of ways. For instance, they provided job opportunities and a source of training and mentoring. To recruit businesses, the initiative made use of existing contacts with the business community such as through networking events and employer-led employability workshops. Subsequently, the initiative provided a tailored business solution by offering a high-quality recruitment service with screened and prepared candidates.

The project was evaluated after two years. It showed that there were clear benefits to career progression and wage increases, as well as a range of soft outcomes. These included greater confidence, work/life balance, technical skills and qualifications, and labour market knowledge. These skills can, in turn, generate further employment benefits in the future. Other programmes with similar features include the Skills Escalator pilots in West London.