00Big cities are crucial to ‘levelling up’

The underperformance of big cities is at the heart of the North-South divide. If the Government is to ‘level up’ the economy then it needs to tackle this major economic problem.

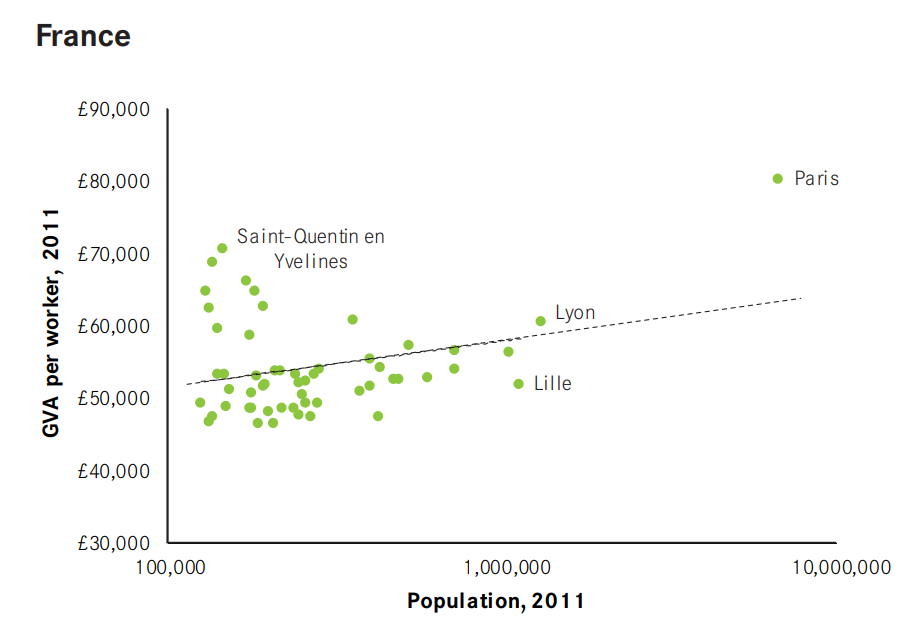

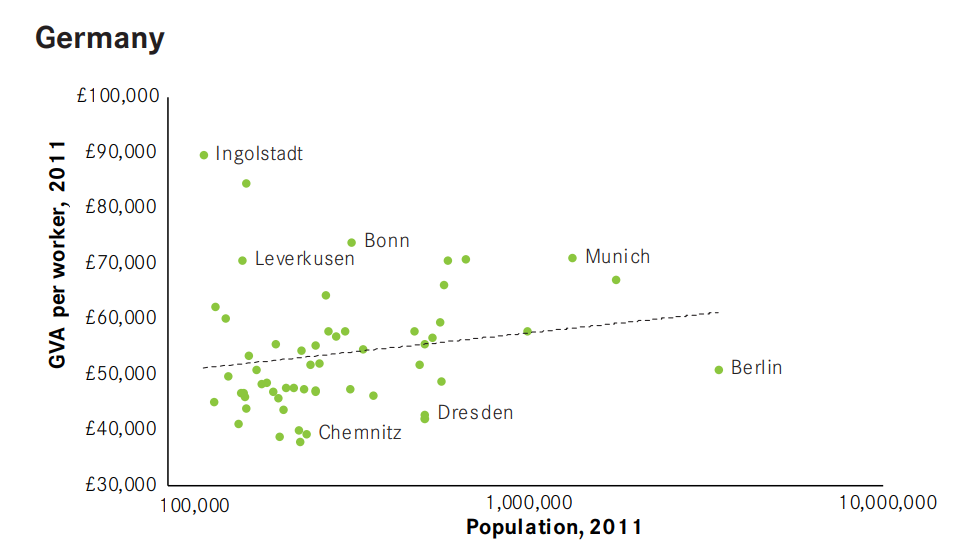

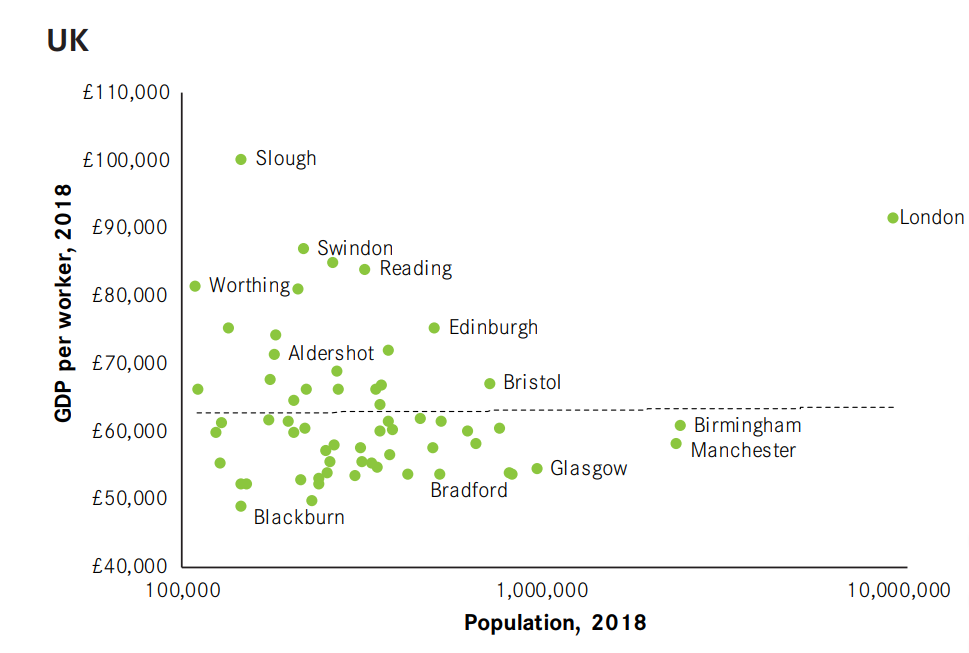

A head-scratching problem amongst urban economists in the UK is that, unlike many other developed economies, UK cities do not become more productive as they get bigger. As Figure 1 shows, in Germany, France, and the United States, there is a positive relationship between city size and productivity, as measured by GDP per worker. Box 1 explains why this is the case. This relationship does not hold in the UK. A number of small cities, such as Slough and Swindon, are more productive than expected and, with the clear exception of London, most large cities are less productive.

Box 1: The link between city size and productivity

Cities cluster people and businesses into one place. Their size gives them a number of inherent benefits:

- Learning: Access to knowledge, through either the creation or sharing of it through face-to-face interactions (known as ‘knowledge spillovers’)

- Sharing: Sharing of infrastructure (e.g. roads, broadband), inputs and supply chains

- Matching: Access to a pool of potential workers

There are a number of costs to being based in cities too, such as higher commercial space rents, congestion and pollution, which are not as large in non-urban locations. Where businesses locate in Britain depends on the trade-off they make between these benefits and costs.

In principle, these benefits and costs increase with the size of a city, a process known as agglomeration, as larger cities give access to greater amounts of knowledge, spread the costs of shared infrastructure across a larger number of people and give businesses access to a deeper pool of workers, and workers access to a greater variety of jobs.

Cities do not just draw on workers from within their boundaries — in 2011, 2.5 million people commuted into them for work. It is the access to this deep pool of workers who live in and around cities that is one of the benefits that cities offer to businesses (see Box 1).

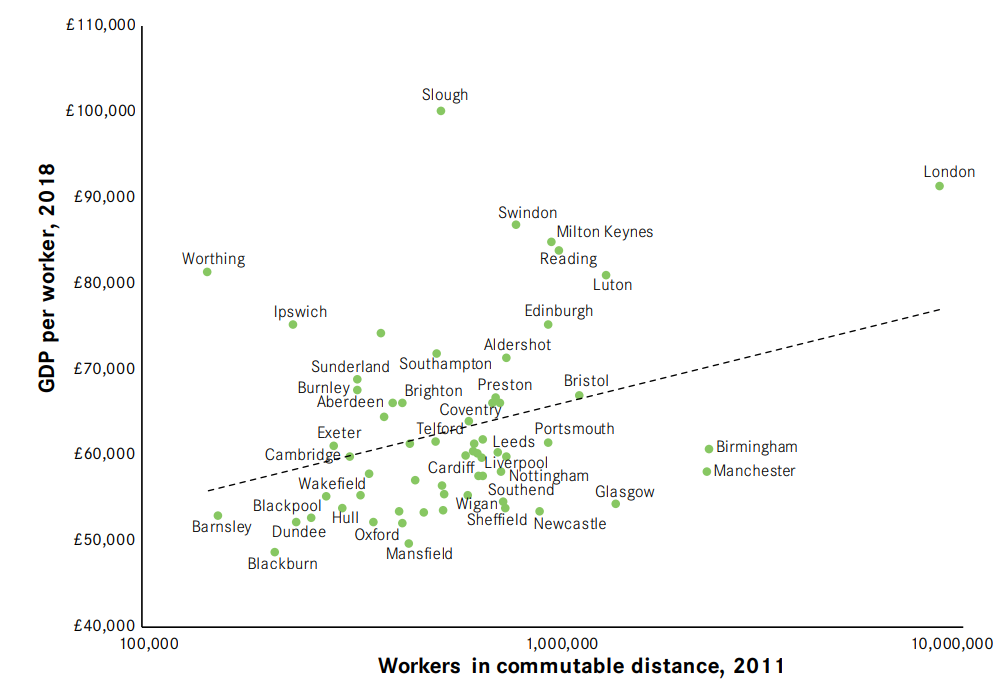

Adjusting the size of the city to take account of people of working age in commutable distance, rather than just looking at the population of the city itself, the relationship between size and productivity changes (Box 2 sets out the definition of the surrounding area). As Figure 2 shows, using this definition of city size changes the relationship between scale and productivity in the UK to positive, which looks more like that seen in other developed countries.

Box 2: Defining areas surrounding cities

Surrounding areas are non-urban areas which are considered to fall within the travel-to-work area of cities. This varies from city to city and is determined by the average distance that a worker living outside of a city travels to get to their job in the city, calculated using data from the last Census. For example, the travel catchment for London is equal to 63km, but for Worthing it is equal to 20km.

More specifically, this adjustment addresses some of the ‘overperformance’ of a number of smaller cities in the Greater South East shown in Figure 1. It shows them to have labour markets more like medium-sized cities than small ones, and this will have an impact on the location decisions that a business makes.

What this change in measurement does not address though is the underperformance of most of the UK’s large cities. Cities such as Manchester, Birmingham and Glasgow remain at the bottom right of the chart, when they should be closer to London. They continue to have productivity levels well below what is expected of cities of their scale, and are not playing the role that cities such as Lyon, Munich and Cologne do.

This is a real problem for the UK economy. When viewed as a point on a chart or line in a table, all places are implicitly given equal weighting. But the sheer scale of big cities means that this is not the case. Their underperformance affects many more people than the underperformance of smaller places, and has much larger implications for the national economy.

Looking at how far underperforming cities sit below the trend line in Figure 2 illustrates this. The difference between the actual productivity of a city and what it would be if it sat on the line gives an estimate of the output gap resulting from its underperformance. On this rough measure, Glasgow has the largest gap (24 per cent), and is followed by Mansfield, Newcastle and Manchester.

Figure 3: Cities with the largest estimated output gaps, 2018

| City | Output gap | GDP change (m) | |

| 1 | Glasgow | -24% | £7,400 |

| 2 | Mansfield | -24% | £1,200 |

| 3 | Newcastle | -22% | £4,900 |

| 4 | Manchester | -21% | £15,300 |

| 5 | Sheffield | -20% | £3,900 |

| 6 | Blackburn | -19% | £700 |

| 7 | Newport | -18% | £1,100 |

| 8 | Southend | -18% | £1,100 |

| 9 | Bradford | -17% | £1,900 |

| 10 | Doncaster | -16% | £1,100 |

So in percentage terms, Manchester’s output gap is similar to Mansfield’s, but in absolute terms they are very different. This is where scale becomes important.

If Mansfield were to close its output gap, the UK economy would be £1.2 billion larger, with the 448,000 people in commutable distance of Mansfield potentially benefiting from the higher wages and greater job opportunities that Mansfield would offer.

If Manchester closed this gap, the UK economy would be £15 billion larger, which would have positive implications for the 2.4 million people who live in commutable distance.

Looking at all cities below the line highlights this further. There are 31 small- and medium-sized cities that sit below the line, such as Newport, Wakefield and Doncaster. If all of these cities closed their output gaps, the UK economy would be £22.5 billion larger. There are eight large cities that sit below the line. If this much smaller group of cities closed their output gaps, the UK economy would be £47.4 billion larger — equivalent to adding two extra economies the size of Newcastle to national output. Manchester, Birmingham and Glasgow account for 70 per cent of this gap. While illustrative, these numbers show the size of the prize of improving the performance of our largest cities.

The point of this is not to argue against investment in smaller places — there are many good reasons to do so. But it shows that focusing on smaller places alone, and ignoring the continued underperformance of large cities, will not deal with the Government’s commitments to ‘level up’ different parts of the UK. And, as previous Centre for Cities work shows, the relationship between cities and towns means that it is not likely to deal with the issues that smaller places face either. Successful cities ‘pull up’ the performance of towns around them.

Box 3: The contribution of London

In Figure 2, London lies well above the trend line. Its actual productivity in 2018 was 16 per cent higher than this simple model would suggest based purely on its size. This equates to £85 billion, or 4 per cent of the national economy – the equivalent of four Newcastles. This shows the importance of continued investment in London, such as projects like Crossrail 2, to help it deal with the costs of its growth like congestion and unaffordable housing.

What explains this underperformance?

As Box 1 discusses, cities in principle offer a number of inherent benefits which increase with size. A number of British cities in general, and big cities in particular, are not offering these benefits to the extent that they should be. Namely, they are not offering businesses access to knowledge and talent.

While all large cities offer access to a large number of workers, most do not offer great access to skilled workers. In terms of the share of workers with a degree, Leeds is the only underperforming large city that has a share higher than the British average (it also has the smallest output gap). The same applies for workers with no formal qualifications, with Leeds being the only city to have a smaller share of people with no qualifications in its city or surrounding area.

Knowledge spillovers occur over very small distances, especially in dense city centres. A number of large cities have seen a resurgence in their city centres in recent years, attracting higher-skilled businesses to take advantage of the knowledge spillovers to which they give access. Despite this resurgence, their city centres still play a small role in the overall economy, and this resurgence needs to continue if the output gap is to close.

An efficient public transport system is needed to link people to jobs in cities, particularly those in city centres. Forthcoming work for Centre for Cities will show that the performance of the transport system is a particular issue in big cities, and complements work done by the Open Data Institute on the poor performance of the bus network in Birmingham. For large cities to make the most of the workers they have living in and around them further investment in their transport systems is required.

What needs to change

While there has been justified discussion on the struggles of so-called ‘left behind’ towns in recent months, it is the underperformance of our big cities that affects the largest number of people and has the biggest drag on the national economy. The UK is an anomaly in this respect. Without addressing this the Government will not be able to ‘level up’ the performance of different parts of the country.

The focus of policy must be to improve the benefits that big cities in particular offer to businesses. They must offer more attractive spaces to do business, particularly in their city centres, offer access to a large pool of skilled potential workers, and connect these workers to jobs through a well-functioning transport system.

So here is what needs to change:

- Focus on the city-centre economy of big cities in particular, ensuring there is sufficient commercial space for business.

- Prioritise the improvement of skills of residents, with particular focus on improving maths and English skills for those workers lacking them, and improving school performance for the next generation.

- Improve the performance of the public transport network within and around the cities, using bus franchising powers where available, creating Transport for London-style bodies and investing in new infrastructure where needed.

- Extend mayoral devolution deals to cover big cities that currently do not have them, and extend the powers of existing mayors to at least match the powers of the Mayor of London.

- Negotiate multi-year ‘single pot’ budgets with mayors, giving them full control about how this money is spent in their area and the ability to plan over a number of years.