09How does policy explain where houses are built within cities?

The viability of redevelopment in the existing suburbs will vary between cities and neighbourhoods, thanks to individual characteristics such as their boundaries and terrain, and the economics of their housing market.

If the pattern outlined above reflects these characteristics, or greater demand to live in certain city centres and on the outskirts of cities than in the existing suburbs, it does not necessarily raise an issue for policymakers.

But if this is the result of restrictions on new supply in the suburbs, then it would suggest there is a problem with the way the planning system manages the trade- offs which emerge from how it controls development. It would indicate that the planning system helps decouple the supply of new homes from demand by how it shapes decisions on redevelopment in the existing suburbs, thereby deepening housing shortages in certain cities.

The patterns above are caused primarily by two different factors. These are:

- How the planning permission system makes suburban intensification risky and costly to builders

- How government housebuilding policy encourages supply in city centres and suburbs

Planning permissions in suburbs are too unpredictable

Many of the decisions and designations in the design of the planning system explicitly reduce or prevent development in specific locations. For example, the Green Belt restricts the supply of land for development on the outskirts outside places like Bournemouth or Manchester. Protected views and heritage considerations in city centres, such as those in Oxford or of St. Paul’s Cathedral in London reduce the height and supply of new developments in city centres.

While these designations – especially the Green Belt – may shape where new land is allocated for development on the outskirts of cities, they cannot explain why the existing suburbs consistently see so little supply.

The planning system is “plan-led”. After a local authority issues a “Call for Sites”, landowners present land to be allocated for development in the local plan. Such sites – typically on the outskirts of cities – that are accepted into the local plan after assessment can usually expect to receive planning permission at a later point. But local plans rarely allocate development sites in built-up areas on land where there are already homeowners.

The plan-led process requires councils to allocate enough land in their plan to account for five years of local housing need. This can be trickier in existing built up areas where sites are typically smaller. Development within the

existing suburbs, whether it is “infill” construction which slots between existing properties, or “intensification” where properties are demolished and higher density housing is built in its in place will instead be expected to proceed through “windfall” sites that come forward for development from landowners despite not being identified and allocated in the plan-making process.

The fragmented landownership of many suburbs often requires that builders purchase and assemble several smaller lots into a single site before development of this type can proceed. This is an underlying issue of suburban development, and is inherently complicated, time-consuming, and risky. Adjacent homeowners in the existing suburbs rarely wish to move, and hold-outs can delay or scuttle schemes by refusing to sell. But the reliance on windfall sites in the suburbs makes such redevelopment even riskier for builders than development on sites allocated in the local plan as the navigation of the planning process is less predictable.

For instance, consider a builder who wants to redevelop two or three semi- detached properties into a small mid-rise development of nine or so dwellings. They must spend time and money searching for landowners adjacent to each other in high-demand locations who are willing to sell; acquiring the properties either outright or with an option agreement; designing a proposal which is suitable for that site; and proceeding through the planning process all before they know whether they will be granted planning permission.

Even if planning officers recommend it for approval, it will in most cases still have to pass by majority vote in councillors’ planning committee to become lawful development. If their proposal is rejected at any stage in the planning process, then they will have lost a considerable amount of time and money, and no new homes will have been built.

If planning in existing suburbs was more predictable and less risky, then building new homes in these places would be more feasible to builders because they would have greater certainty that their upfront costs would not be wasted. For instance, part of the reason London sees pockets of densification around certain train stations because Public Transport Accessibility Levels (PTALs) have been used to guide redevelopment in London.

Tax discourages suburban intensification

One of the barriers towards suburban densification, even in local authorities which support it, is how new development is taxed. Currently, Planning Practice Guidance states that developments of nine or fewer homes are exempt from affordable housing contributions in Section 106 negotiations. As a result, developers engaging in infill development are encouraged either not to

provide more than nine dwellings in smaller schemes, or to pursue much larger schemes of dozens of dwellings where they can easily absorb the cost of such contributions.

This makes it much harder to provide smaller schemes of a dozen or dwellings which would require moderate land assembly but may be more politically acceptable in suburban neighbourhoods than large developments. Even if developers have the ability to assemble such land and the encouragement from local authorities to do so, both the actual financial contribution for affordable housing Section 106 requires and the highly uncertain negotiations that underpin it make such intensification unviable.

Policy pushes housing supply into the outskirts and city centres

In addition to the discretionary granting of planning permissions, the other key feature of housing policy is that local authorities face a housebuilding target from central government. These targets are calculated primarily on the basis of demographic predictions from the ONS, with a small multiplier for affordability that does not capture the full difference in prices between cities. Councils

are required to build to their target, and though significant underperformance results in consequences from central government, there is little incentive or encouragement for councils to build more than their target.19

Given their fixed targets, local authorities allocate their required new houses where it is easiest and least costly for them to do so. Depending on the local authority in question, these include city/town centres and greenfield development on the outskirts, because:

- Development is easier where landownership is simpler, which it is in the outskirts of cities (typically farmers or large landowners) and the city centres (either local authorities or institutional investors) compared to the suburbs (many existing homeowners). This partly explains why housing estates owned by councils and housing associations have been frequently redeveloped at higher densities in recent years.

- Per house, larger planning applications require much less work for local authorities’ planning departments than smaller applications. Cuts to local government have fallen hard on planning departments, and many struggle to have the capacity to manage technically difficult applications on small sites in existing suburbs for a few houses while meeting their targets.

- It is less difficult politically to supply new homes in city centres and in greenfield development on the periphery of cities because few people live nearby to In contrast, the existing suburbs have lots of voting residents who may object to new housing.

The process can be illustrated in Figure 10. Regardless of how large their housebuilding target is or how many houses local authorities then try to build, new supply will flow to the areas where it is least politically costly because new supply is in practice capped by the target.20

Figure 10 underpins the importance of intensive neighbourhoods either in city centres or the outskirts to addressing housing shortages in cities, and the flaws with measures to develop “compact cities”. Part of the rationale for policies such as the Green Belt is that by blocking urban expansion they encourage suburban densification. But this does not happen – the barriers to suburban development in Figure 10 are inherent to how the current planning process functions.

Measures to reduce development on the outskirts of cities do not encourage the “recycling” of already-developed land. They just reduce the supply of new homes, making the housing crisis worse.

This process will shape the pattern of supply within a city regardless of how many new homes are actually built. Even if a local authority does not manage to build to its target, the houses that are developed will still comply with this pattern because it always minimises the costs and risks the council and developers face within the planning system from building more homes.

Reform must increase cities’ overall supply, not displace it

Solving the housing crisis requires reconnecting the local supply of new homes to local demand, and boosting the supply of new homes in expensive cities. There is little point in simply displacing new supply from a city centre or outskirts into a city’s existing suburbs without increasing the total growth in housing.

The political costs that densifying the suburbs would entail present a problem to those who wish to see reforms to the planning system. Radically changing the character of the existing suburbs through large redevelopment is not feasible due to the obstacles described above. But it is only worthwhile for policymakers to undertake such politically costly reform if it achieves a major increase in total housing supply.

The dormant suburbs could boost housing supply by only building a little more

This challenge facing densification is solvable, because as so many of the suburbs are dormant, each of these neighbourhoods requires only a small increase in construction to greatly increase cities’ total new housing supply.

This can be demonstrated in a hypothetical scenario showing how housing supply would change if cities brought the rate of housebuilding in each of their dormant suburban neighbourhoods up to their average housebuilding rate for their suburbs, and changed nothing else.

As an example, the average growth in housing stock for Derby’s suburbs was 3 per cent across 2011-19. This growth was very concentrated in certain areas. Some 66 per cent of suburban neighbourhoods in Derby’s saw their housing stock grow by below that average rate, with 27 per cent seeing no construction at all. It is possible to calculate how many homes Derby would have built if those 82 per cent of neighbourhoods had instead built at that average suburban rate of 3 per cent. Neighbourhoods in Derby’s suburbs that grew at 3 per cent or any other rate greater than the average would see no change in their housing growth in this model.

Figure 11 shows how such changes at the neighbourhood level would change the pattern of housing supply across all cities, and can be compared to the current pattern of supply in Figure 7. In this scenario, the average neighbourhood – which has 700 homes – that does see a boost to housing supply in Figure 11 builds just under four more homes every year from 2011 to 2019, or 30 additional houses. These new homes would have resulted in a more than 3 per cent increase to total housing stock in cities and towns relative to 2011, or 446,000 new homes.

Figure 11: Supply of housing in suburbs in England and Wales if all suburban neighbourhoods had built at their suburban average rate, 2011-19

The share of suburban neighbourhoods that are building between three and 12 houses each year has increased from 19 per cent to 78 per cent in this scenario. Instead of contributing to 24 per cent of all new homes as they did in Figure 7, they would make up 54 per cent of all new homes. There would be no dormant neighbourhoods, as every neighbourhood would be building at least one house each year.

Intensive neighbourhoods still make up 4 per cent of suburban neighbourhoods, as the total number of houses they would build has not changed. But the pressure on them to provide the bulk of new supply has reduced, with their share of all suburban housebuilding falling from 45 per cent in Figure 7 to 19 per cent in Figure 11.

This would have resulted in an additional 446,000 homes across every city in England and Wales between 2011-2019, or 56,000 additional houses every year. This scale of suburban densification would have increased total urban housing stock by over 3 per cent, and almost closed the gap between the Government’s national target of building 300,000 homes a year in England and the current rate of net new dwellings of 241,000 a year.

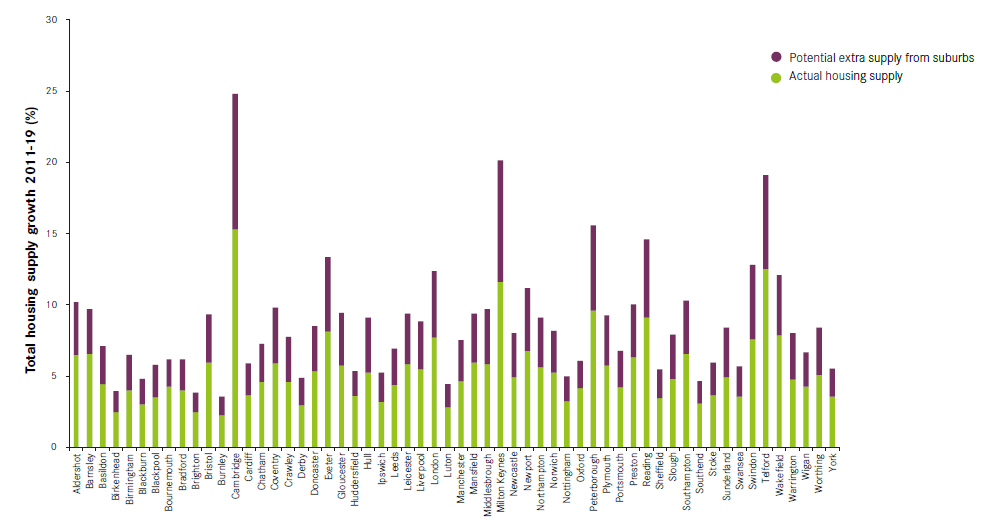

Realistically, the supply of new homes in the existing suburbs of cities and towns will be driven by demand, and whether land values can support redevelopment. But to demonstrate how increasing construction in the dormant suburbs would affect individual cities, Figure 12 shows how the scenario would change supply. The actual supply of new homes from 2011-2019 is depicted in green. Purple shows what total housing supply would have been for each city if every neighbourhood had built housing at least at the current average rate for that city’s suburbs, as in Figure 11.

Figure 12: Housing supply by city, if every suburban neighbourhood built by their suburbs’ average, 2011-19

If every neighbourhood had been brought up to their suburban baseline, the growth of new urban housing supply since 2011 would have been 56 per cent faster. This would have had a major impact in some of the most unaffordable cities in the country. The number of houses built in Milton Keynes would have been 73 per cent higher, in London 56 per cent higher, and in Reading 54 per cent higher. Brighton and Exeter, the two expensive cities covered in this paper, would have provided 46 per cent and 58 per cent more new homes respectively than they did in reality. Manchester would have built 58 per cent more too.

Prices will determine which cities see the most densification

Even if reforms were implemented to increase construction in the existing suburbs, in practice, market conditions would and should determine where suburban housebuilding will increase, with more expensive cities seeing a larger effect than those with cheaper land.

This effect is desirable for two reasons. First, the most expensive cities, such as London, Bournemouth and York, are signalling through their high house prices that there is a severe shortage of homes in these cities. Building more homes in their suburbs will help reconnect the supply of homes to those cities where new homes are in high demand.

Second, suburban redevelopment is more costly than building on undeveloped land, which means the land must be expensive to justify doing so. In cities where land is cheaper, housing can be built at lower housing densities on such undeveloped land and remain affordable. Redevelopment of the suburbs in these cities at higher densities would entail higher building costs and less space for residents, without saving residents much money on the price of land. In unaffordable cities, however, where land values are high and rising, higher densities make it possible to split the cost of expensive land between more households. This benefit makes the higher construction costs of suburban redevelopment in these cities worthwhile.

Densifying the suburbs will be difficult

Development in the suburbs has been proposed and implemented before, but it is challenging both politically and technically. For instance, the number of “small sites” the new draft London Plan expected to deliver was rejected by the Planning Inspectorate as “unrealistic”.21

A large role for the public sector would likely require the use of compulsory purchase orders to assemble land in the suburbs, as was controversial in New Labour’s Pathfinder programme.22 The biggest plots of lands councils or housing associations already own are frequently social housing estates. Regeneration schemes for these sites have become increasingly contested in recent years, with the Haringey Development Vehicle collapsing in 2018 due to activist opposition.

Giving a greater role to the private sector to densify the suburbs would in contrast entail more incremental development than a public-sector approach. However, this can be controversial too. One of the first things the Coalition Government implemented in 2010 was a ban on “garden grabbing”, which allowed brownfield development on gardens.23

Private sector densification, site-by-site, will create an urban form which is more varied in building stock, size, and appearance than currently exists. Design codes, such as those suggested by the Building Better Building Beautiful Commission, may reduce some of the aesthetic impacts, especially to facades, but such densification will require streetscapes to change.24

What will suburban development look like?

Development of the existing suburbs will entail different things depending on the nature of the site. It could include “infill” development of new suburban homes on existing areas of green space within the suburbs, such as golf courses, gaps between houses, or vacant lots. It also covers intensification, and the demolition and redevelopment of existing properties to provide more dwellings at a higher density.

For example, Goldsmith Street in Norwich attracted much attention for being the first council housing and Passivhaus development to win the RISA Stirling Prize, an architecture award, in 2019, but as important is its being a redevelopment

of existing homes in the built-up suburbs of the city, on council-owned land. Marmalade Lane in Cambridge is a similarly-designed scheme led by a non-profit, which was infill development within a suburb built in the early 2000s.

Other examples from the private sector tend to involve simpler land assembly, but can still be fraught with difficulty. For instance, 291 Hills Road in Cambridge, less than a mile from the railway station, is a single site in the suburbs currently occupied by a large mansion, which has proceeded through planning to allow for the development of 14 new flats after a previous rejection.25 Likewise, 31-33 Dollis Avenue in London, near Finchley Central underground station, is a single structure with semi-detached dwellings, and was granted permission in 2017 to be redeveloped into nine new flats, after repeated attempts to do so since 1998.26

How this can work theoretically in terms of design principles across different sites has been the subject of considerable thought by academics and architects such as Ben Derbyshire, Yolande Barnes, and organisations such as Create Streets and the Prince’s Foundation.27

Some of these ideas have then been incorporated into the National Design Guide released last October, the Government’s Building Better, Building Beautiful Commission and Supplementary Planning Guidance by local authorities such as Croydon’s suburban design guide, as part of a goal to build over 10,000 new homes in the existing suburbs of Croydon by 2036.28 These can help reconnect housing supply to demand, and thereby improve affordability, if they can improve the predictability of the planning process. Currently, the primary risk in the development process in local authorities is uncertainty as to whether planning permission will be granted or not. If permission can be assured, conditional on certain design elements, this will reduce the planning risk faced by builders.