02The role of manufacturing in Sheffield City Region’s economy

Sheffield City Region is one of the largest city-regions in England, but in the decades following the decline of steel and coal production, its economy has performed poorly as it has struggled to adapt to economic change.3 The foundations of the city region’s urbanisation were its exporting strengths in manufacturing. In 1911, there were 182,000 manufacturing jobs across Sheffield City Region, which constituted 43 per cent of all employment.

But the city region’s economic performance declined due to deindustrialisation over the second half of the 20th century, in common with many other cities.4 Although manufacturing’s share of local employment was still 43 per cent in 1971, this shrank to 11 per cent in 2011 (63,000 jobs).

While other cities like Leeds and Reading have been able to transition their economies from manufacturing to higher-skilled and more knowledge-intensive activity, Sheffield City Region has struggled to do this and has largely replicated an existing structure of low-paid and low-skilled work. As a result, the average wage in the city-region is low at £459 a week, compared to a national average of £539. Sheffield City Region’s wages are also lower than in other core cities such as Leeds and Manchester, where weekly wages are £540 and £526 respectively.

Why Sheffield City Region’s overall economy does not perform as well as other large cities

Exporting firms are key to local economic performance. These firms sell to markets mostly outside their location, whether to other cities, regions, or abroad. This includes everything from car assembly and forging steel, to high-skilled services like architecture and technology. They stand in contrast to local services such as dry cleaners, solicitors, and restaurants, which sell mostly to their local market. These local service firms have similar levels of productivity across the country and therefore cannot explain geographic differences in economic outcomes between cities. Local services need to locate in areas where there are lots of customers with money to spend, usually cities. In contrast, as exporters’ markets are always elsewhere they can choose to locate in the cities that suit their unique needs. This explains why cities’ economic performance varies so much – cities offer different benefits that can meet the distinct needs of high-and low-skilled exporting firms, which then shapes the performance of local services.

For high-skilled exporting firms, the crucial resource a place must possess is knowledge. Firms in areas like software development, financial services, and engineering locate their highest-paid work where they can find skilled workers to take on the specialised roles their activity requires.

For low-skilled exporting activity such as logistics or assembly plants that do not need such specialised workers, the priorities are instead keeping the costs of land and labour as low as possible. This means firms locate in places where land is cheap and wages are low. As a result, they struggle to pay high wages or sustain demand for local services.

A city’s ability to generate knowledge is therefore decisive in terms of achieving high productivity and wages in an urban economy. Cities with weak skills profiles struggle to appeal to higher-paid exporting firms.

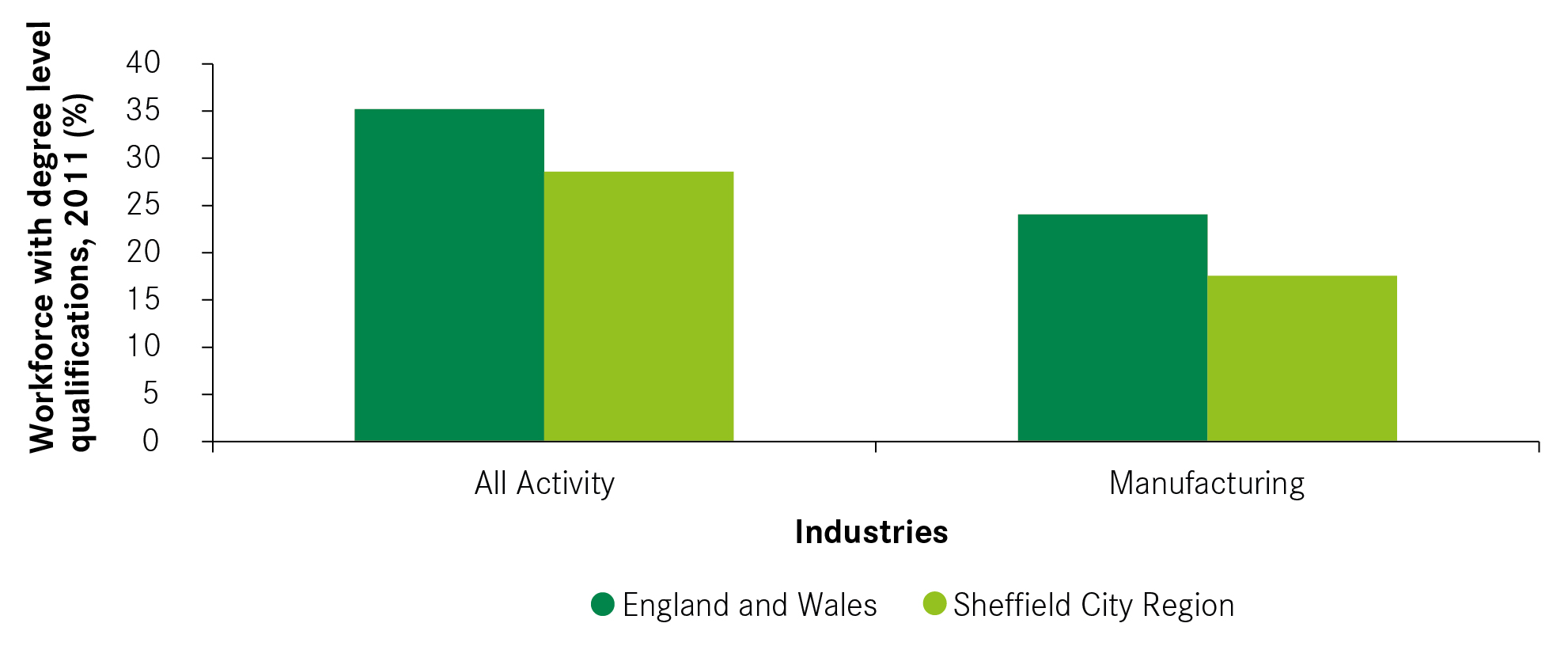

This explains the economic performance of Sheffield City Region. In the average UK city, 49 per cent of exporting firms are high skilled, but in Sheffield City Region it is only 20 per cent. This is also reflected in the skills of manufacturing workers – Figure 1 shows that only 18 per cent of workers in manufacturing in Sheffield City Region have degrees, compared to 24 per cent in England and Wales as a whole, and, for example, 46 per cent in Crawley, which has the highest share of any city in England and Wales.

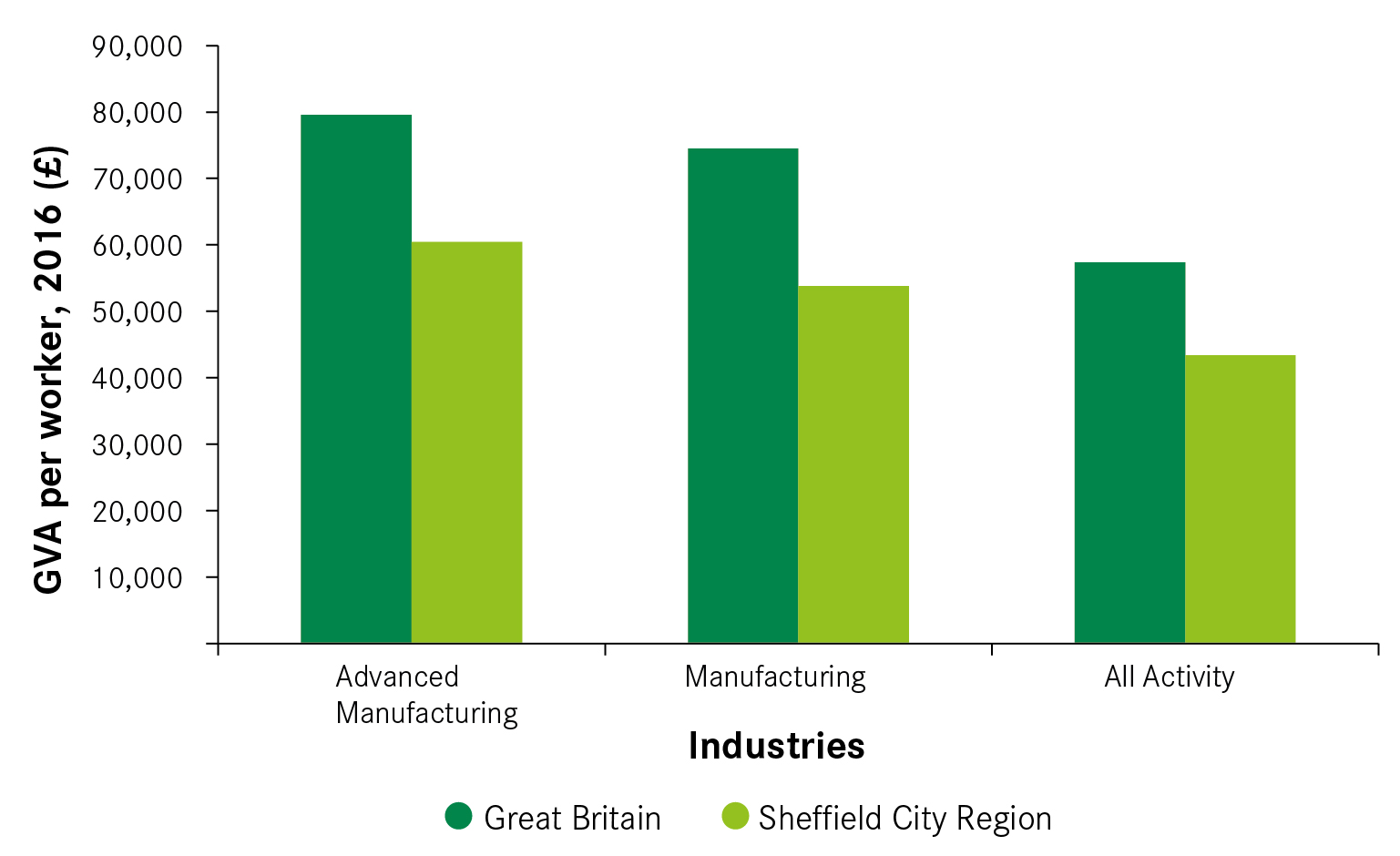

The skills deficit means Sheffield City Region tends to appeal to exporting businesses as a place of lower-cost and lower-paid production. As a result, Sheffield City Region’s economy has lower productivity compared to the rest of the country. Figure 2 shows that productivity is lower across all activities in the Sheffield City Region, including manufacturing and advanced manufacturing than the national average.

Box 1: What is advanced manufacturing?

Manufacturing plays an important role in the economy of many British cities, both in terms of jobs and trade with other cities, regions, and countries.

Most knowledge-intensive manufacturing is referred to as ‘advanced manufacturing’. This activity requires high-skilled workers, small and often experimental production runs, and the use of information technology to monitor the production process. It is closely related to engineering and is a key part of “Industry 4.0”.

This report uses a narrower version of an OECD/ONS definition of medium-high tech manufacturing to create an index of advanced manufacturing, for which the full lookup is in the appendix.

The advanced manufacturing in the Sheffield City Region tends to be lower-skilled than that found in other cities. Looking at the different types of activity that can be grouped under advanced manufacturing, Figure 3 shows that Sheffield City Region has a particular concentration in metal fabrication, and a lower than average representation in most other fields. The highest-skilled areas in advanced manufacturing like engineering and research and development are the second largest share of advanced manufacturing activity, but still a smaller share than the

national average.

Figure 3: Share of workers across different types of advanced manufacturing and engineering activity

Not only are advanced manufacturing and engineering workers in Sheffield City Region as a whole over-represented in low productivity fields, but many of these fields also perform at a lower level of productivity than the national average. Figure 4 shows that engineering and scientific research face a large productivity gap in the Sheffield City Region, with engineering only 64 per cent as productive as it is in the rest of the country, and private R&D being only 44 per cent as productive as the national average. These are fields that are particularly important for providing high-skilled advanced manufacturing work. Across the city-region, they currently underperform compared to other places.