03Why are strong economies good at creating job opportunities for low-skilled people?

Cities that have been able to attract high-skilled exporting businesses are both the strongest economic performers and have been able to provide better economic outcomes for low-skilled people. But, strong economic growth can come at the cost of increased house prices, which risks pricing out low-skilled people from these cities.

As this chapter will explain, the varying economic outcomes for low-skilled people are closely related to the mechanisms through which different low-skilled jobs are created.

Different cities offer different types of low-skilled jobs

There are two types of low-skilled private sector jobs that cities can create: those in local services, such as retail and leisure, and those in the exporting sector, such as manufacturing and logistics.

The map in Figure 8 shows how the composition of low-skilled jobs varies across the country. Most of the low-skilled jobs created in cities in the Greater South East, which generally have stronger economies, are in local services occupations. In these cities, almost eight out of 10 low-skilled jobs are in local services, with London and Cambridge having the most.

On the other hand, the composition of low-skilled jobs in cities in the North and Midlands is more skewed towards low-skilled exporting jobs. In these places, just over six out of 10 low-skilled jobs are in local services, while four in 10 are in the exporting sector.

These differences are the result of the types of exporting businesses that cities attract.

By attracting high-skilled exporters, cities with strong economies indirectly create low-skilled

jobs too

Low-skilled jobs in local services – such as retail and leisure – naturally emerge in close proximity to any population centre. When a new neighbourhood is built, together with new houses and perhaps some offices, local services such as supermarkets, cafés and hairdressers are likely to open nearby.

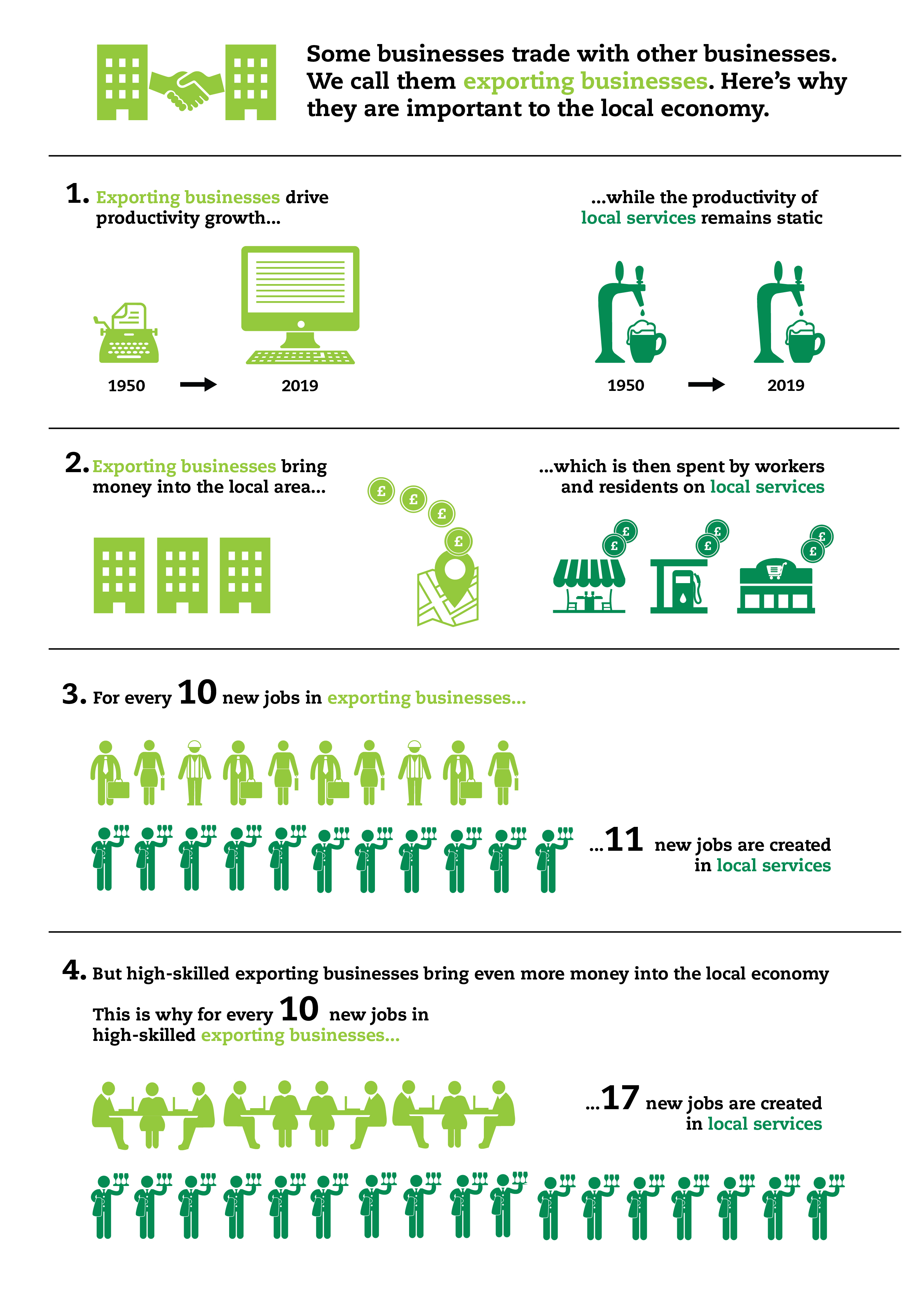

But the extent to which each place will go beyond a basic provision of local services depends on the wealth available in a local economy – which, as seen in Box 2, depends on their ability to attract exporting businesses. This process is called the multiplier effect.8

All types of exporting jobs – both high-skilled and low-skilled – have a multiplier effect; however, the size of this effect varies depending on the type of job.

For example, between 1998 and 2015, where 10 new exporting jobs in urban Britain were created — other things being equal — 11 new jobs in low-skilled local services were also created (see Box 4 for methodology). But high-skilled exporting jobs had a much bigger multiplier effect. For every 10 new high-skilled exporting jobs created in the same period, 17 new jobs were generated in low-skilled local services.

Public sector jobs also had a positive multiplier effect, but this has been much smaller, with three new low-skilled local services jobs created for every 10 new public sector jobs.

The implication is that in recent years, cities that have been successful at attracting high-skilled exporting businesses have also been the cities best able to create growth in low-skilled local services jobs too. On the other hand, cities in which growth has been mostly led by the public sector or by lower-skilled export businesses have not experienced the same growth in local services.

Box 4: Methodology – the multiplier effect

The multiplier effect theory has been widely studied by economists all around the world, particularly in the USA by Enrico Moretti.

By following a similar methodology as the one used by Moretti, this report looks at the relationship between growth in exporting jobs and local services jobs in urban Britain in between 1998 and 2015 using data from the Business Structure Database.

As the goal was to identify the impact of export growth on local services growth, we used growth in local services jobs between 1998 and 2015 first, and in low-skilled local services jobs second, as the dependent variables. As independent variables, different breakdowns of exporting jobs were used, firstly looking at the broader impact of export jobs on growth in local services and then breaking down export jobs into low-skilled and high-skilled. An instrumental variable was also introduced to deal with the fact that national economic shocks can affect both growth in exporting jobs and growth in local services jobs, influencing the results.

More details on the methodology can be found in Van Dijk (2017). A full list of industries that fall into the exporting and local services categories can be found in appendix 2, and the results of the regressions can be found in appendix 3.

In contrast, cities with weaker economies mostly create low-skilled jobs by attracting low-skilled exporting businesses

Like high-skilled exporting businesses, low-skilled exporters are too, in theory, able to locate anywhere and decide where to locate based on the benefits different places offer.

However, the more routinised nature of these jobs means the benefits these firms are looking for are different from their higher-skilled counterparts. They still want access to a lot of workers, but they are predominantly looking for lower-skilled workers to fill their vacancies. Their requirements for knowledge are also lower, meaning they do not need to pay a premium for this. This means these firms tend to prefer locations where land is cheaper.11

Given their large pools of low-skilled workers and access to cheap land, it is not surprising to see that low-skilled exporting businesses tend to cluster in cities in the North and Midlands. However, these low-skilled exporting jobs are less able to generate wealth for their local economy or deliver additional local services jobs.