02The economic outcomes of low-skilled people in urban Britain

The majority of low-skilled people and low-skilled jobs are in cities

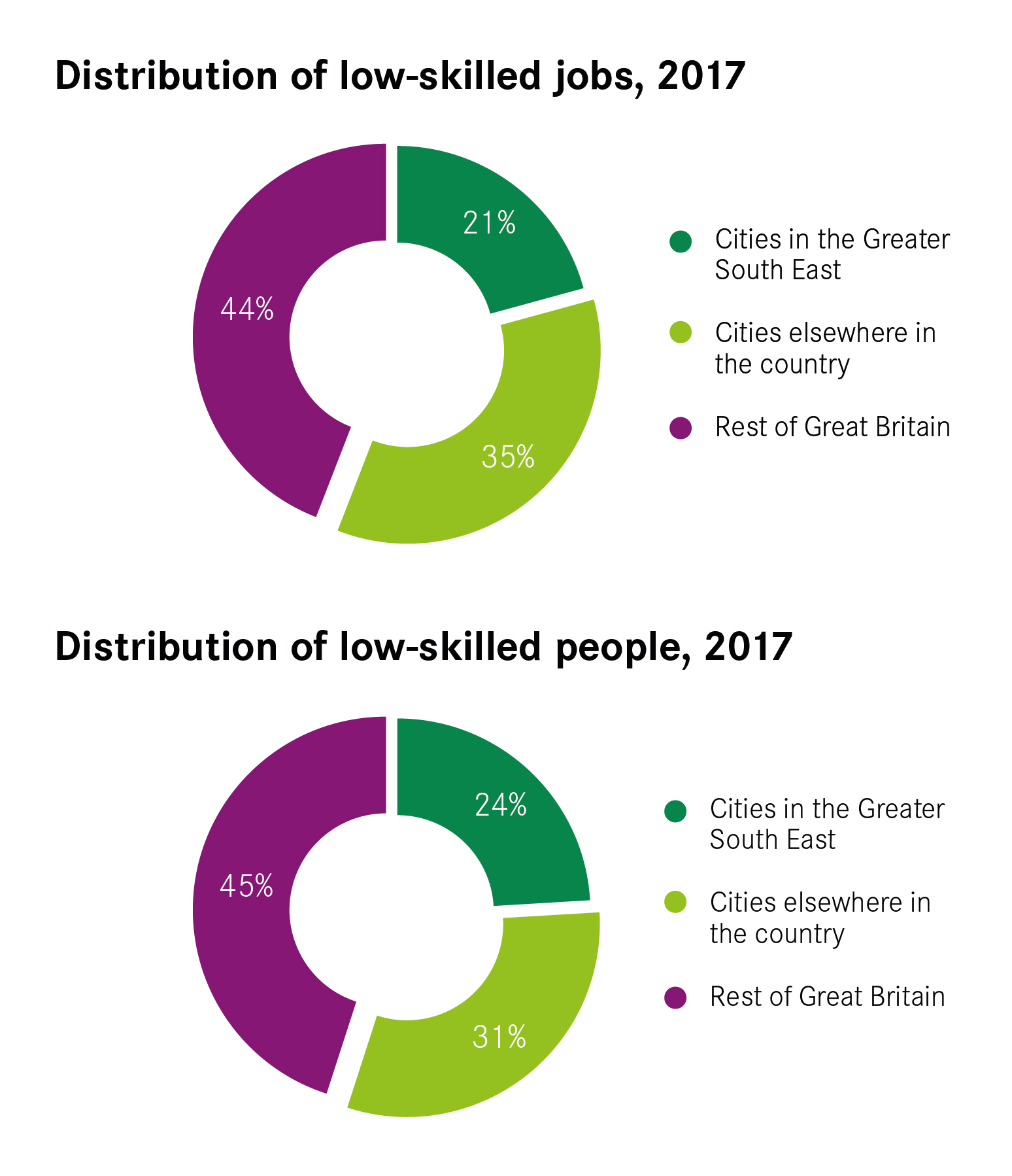

Cities are not just home to the majority of high-skilled jobs and people; they are home to the majority of low-skilled jobs and people too. In 2017, they were home to over four million low-skilled jobs – approximately 56 per cent of all low-skilled jobs in Great Britain – and over four million (56 per cent) working-age people with low-skill qualifications (see Figure 1).

Those with no qualifications at all are, in particular, concentrated in cities. In 2017, almost 2 million working-age individuals with no qualifications lived in cities, or approximately 61 per cent of the entire working-age population with no qualifications in Great Britain.

Low-skilled people and low-skilled jobs play a much bigger role in cities in the North and Midlands

Within cities, low-skilled people and jobs cluster in the North and Midlands. Overall, these cities account for 62 per cent of all the low-skilled jobs and 66 per cent of all the low-skilled people in urban Britain.

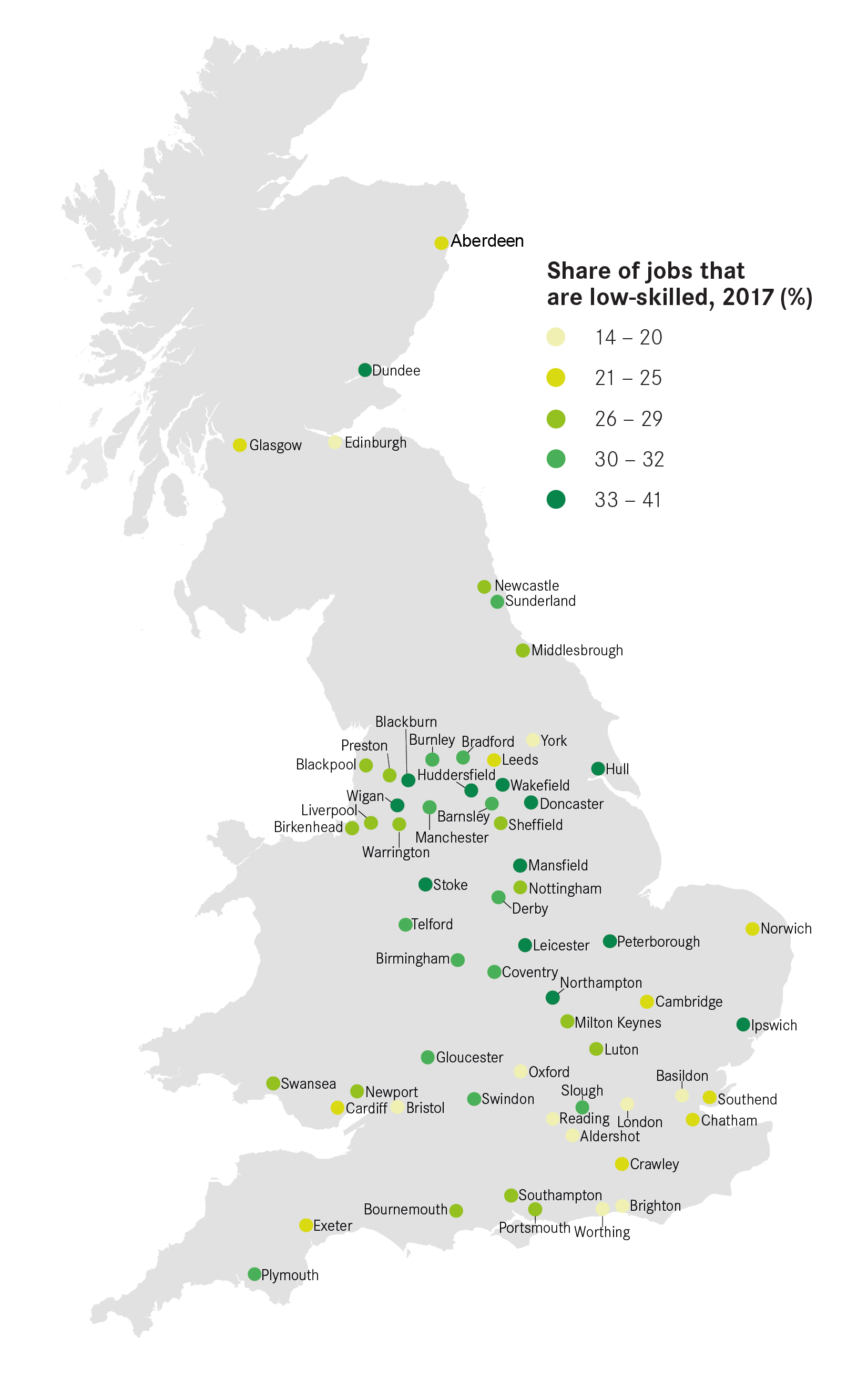

In these cities, low-skilled jobs and people play a much bigger role too. In many cities outside the Greater South East, such as Mansfield, Sunderland and Hull, a third or more of all jobs available are in low-skilled occupations, such as process and plant operatives, customer services and elementary occupations (see Figure 2). This is higher than the national average of 24 per cent and is in sharp contrast to cities like Brighton, Reading and London where low-skilled jobs account for less than 20 per cent of all jobs, a much smaller portion of the labour market.

This pattern is also visible when looking at people’s skills (see Figure 3). On average, 18 per cent of the working age population in Great Britain is low-skilled, but in many cities in the North and Midlands – such as Mansfield, Bradford and Birmingham – almost one in three people are low-skilled. This is almost three times the share of low-skilled individuals in some city economies in the Greater South East such as Oxford, Cambridge and Reading where there is only one low-skilled person for every 10.

It is in cities in the Greater South East, where the economy is stronger, that low-skilled people have better economic outcomes

Cities in the Greater South East have a higher share of high-skilled jobs. In recent years, these cities have grown their stock of high-skilled exporting businesses making their economies stronger (see Box 2).

Box 2: How does a city create a strong economy?

The economic success of a city is determined by its ability to attract exporting businesses.

These businesses sell to many markets – regional, national and international – meaning that places that are able to attract them can benefit from the money these businesses inject into the local economy.

Among the exporting businesses, it is high-skilled exporters, such as engineers and financial services businesses which bring the most wealth to a local economy.

Given their ability to sell to many markets, these businesses are in theory able to locate anywhere. As such, this means that their location decisions are based on the advantages that different places offer to them.

In particular, in deciding where to invest, high-skilled exporters tend to look for two main things: access to knowledge and high-skilled workers. In recent years, cities in the Greater South East have tended to be better at offering businesses these benefits, and this is reflected in the strong economic performance of these places.

Yet, this job creation has not just benefited high-skilled people, but low-skilled people too.

By using Census data it emerges that in these cities low-skilled people have better economic outcomes than those living in cities in the North and Midlands.

Stronger economies can support low-skilled people in three ways:

1. Low-skilled people are less likely to be unemployed in

stronger economies

Unemployment rates among low-skilled people are higher in cities in the North and Midlands than in the Greater South East. In Hull and Liverpool for example, around one in five individuals with few or no qualifications is unemployed, compared to less than one in 10 in Aldershot and Bournemouth.

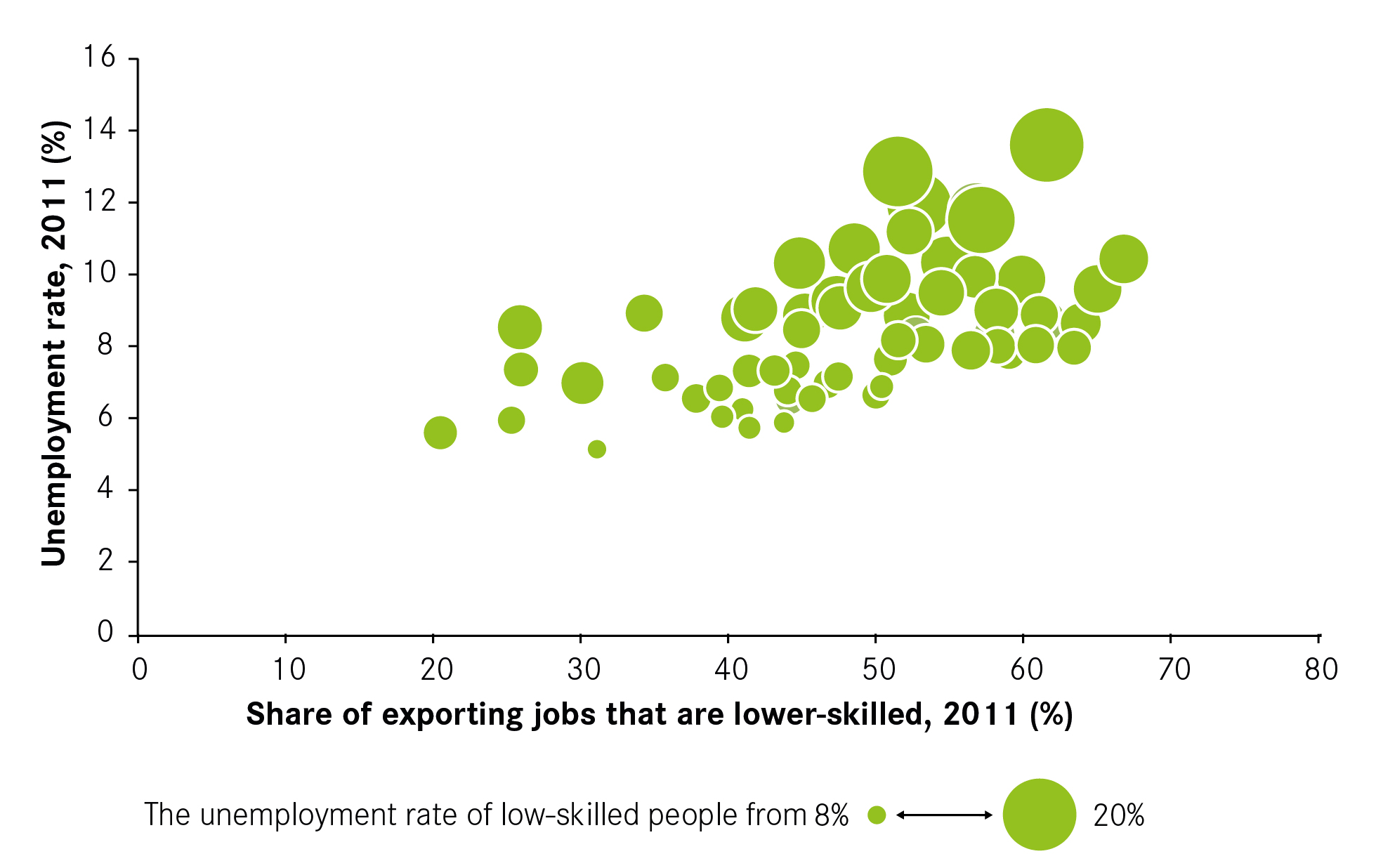

These differences mirror the more general patterns of economic outcomes for individuals in different parts of the country. Hull not only has the highest low-skilled unemployment rate (20 per cent), it also has the highest overall unemployment rate (14 per cent). This contrasts with cities in the Greater South East, where both low-skilled unemployment rates and overall unemployment rates are much lower.

The economic performance of places – rather than the presence of low-skilled jobs – appears to be a key determinant of unemployment rates (see Figure 4). And where high-skilled exporters play a much bigger role in the economy, unemployment rates tend to be lower.

Figure 4: The relationship between the strength of an economy, unemployment, rate and low-skilled unemployment rate, 2011 (%)

2. In stronger economies, there is a more equal balance between low-skilled people and jobs

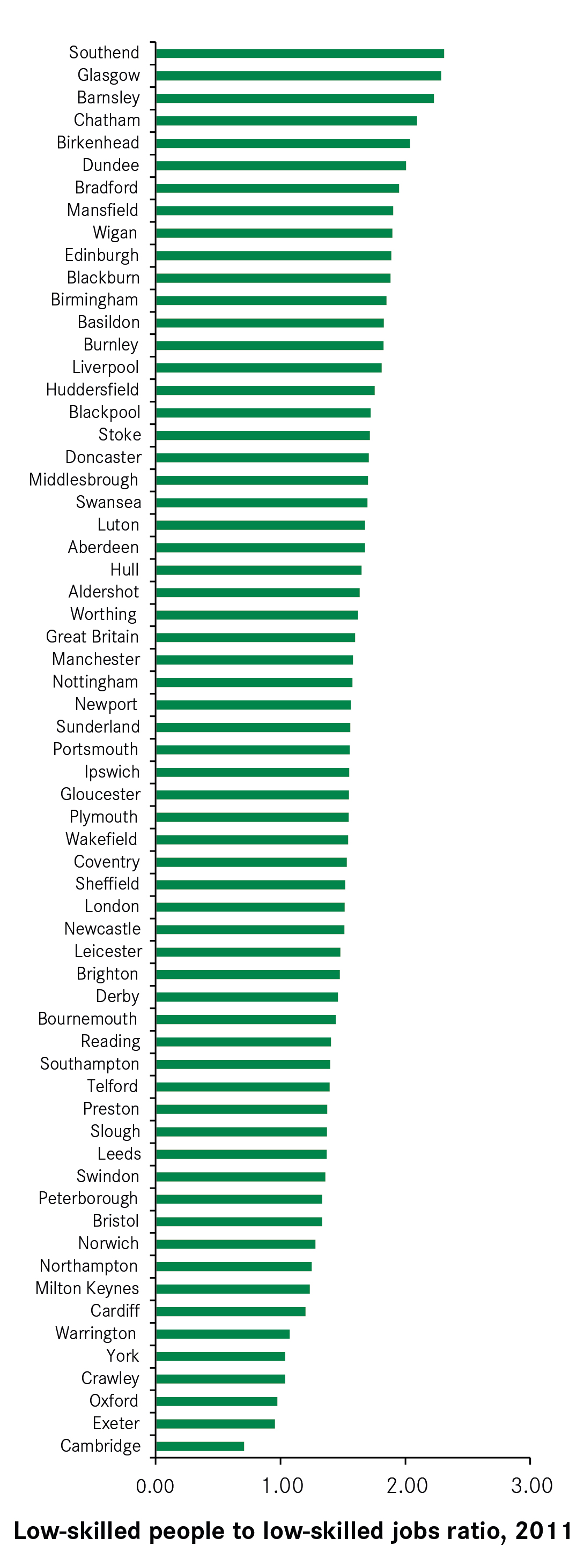

Similarly, while it is true weaker economies are home to a lot of low-skilled jobs, the number of low-skilled people living in these places is much higher than the low-skilled jobs available (see Figure 5).

Indeed, for every low-skilled job in weaker economies,5 there are on average 1.66 working-age people with few or no qualifications. The ratio is even higher for places such as Southend, Barnsley and Birkenhead where there are two or more low-skilled people for each low-skilled job.

There are more low-skilled people than low-skilled jobs in most of the strongest economies too, but the ratio is lower, with 1.43 low-skilled people for every low-skilled job. And the more successful cities are, the closer the ratio is to one low-skilled person per low-skilled job. In Cambridge, Oxford and Exeter meanwhile, there are more low-skilled jobs than low-skilled people.

This means that there is greater competition for low-skilled jobs among low-skilled people in weaker economies than there is in stronger ones.

3. In stronger economies, the low-skilled are more likely to access higher-skilled occupations too

In cities with strong economies, low-skilled people are much more likely to be in higher-skilled occupations than their counterparts in weaker economies. The link between qualifications and occupations is weaker in stronger economies and while a higher share of low-skilled jobs in stronger cities is taken up by individuals with medium-or-high-skilled qualifications, a higher share of low-skilled people fill higher-skilled occupations too.

In Aldershot, London and Reading, approximately 60 per cent of workers with few or no qualifications work in medium-or-high-skilled occupations (see Figure 6). This is higher than in weaker economies, such as those of Wakefield, Sunderland and Doncaster, where the share of low-skilled workers in higher-skilled occupations is around 40 per cent.

As a result, these indicators suggest that the job outcomes for low-skilled people are better in stronger economies than in weaker ones.

However, pressures on housing make the many opportunities strong economies offer less accessible

While it is true strong economies create more job opportunities for the low-skilled, these might not always be accessible.

One of the challenges associated with strong city economies is that success comes with increased pressures on the housing market. Looking at how many low-skilled people moved house, and where to, can give an indication of the effects of high house prices on low-skilled people.

As Figure 7 shows, cities with stronger economies tend to be less affordable. As a result, these cities see a much bigger share of low-skilled individuals who move house choosing to leave the city.

In 2011, on average, the annual house prices in Britain were nine times the annual salary of residents but among the most successful cities, the ratio was much higher. Oxford and Cambridge were the least affordable cities, with house prices at 14 and 11 times higher than annual earnings. These cities also saw the biggest share of low-skilled people moving house and leaving the city. Of all the low-skilled people who lived in Cambridge in 2010 and moved house, 47 per cent left the city. In Oxford, the share was 36 per cent.

Figure 7: The relationship between the strength of an economy, housing affordability and share of low-skilled people moving out of the city

Box 3: Low-skilled people in London

In contrast to other highly successful and unaffordable cities, London does not seem to push low-skilled people out as much.

The large majority (83 per cent) of all low-skilled people who lived in the capital and moved house in 2011 remained in London, while only 17 per cent left the city altogether.

While the data does not allow the tracking of people’s movements within the city, it is plausible to believe low-skilled people who moved house in London have moved further away from the city centre, reflecting the high house price growth inner London has experienced in recent years.

As with all the cities in this report, London here refers to the London Primary Urban Area, which is larger than the Greater London Authority boundaries. See www.centreforcities.org/puas for more information.

Of those low-skilled people who moved, most did not move far. Some 37 per cent of those who moved house and left Cambridge, for example, moved to non-urban areas within the same region. In Oxford, the figure was 27 per cent. Other strong city economies experienced similar patterns, suggesting that the low-skilled people moving out of these cities still value the proximity to these places’ labour markets, but cannot afford to live in them.

Private renters in areas of limited housing supply particularly feel this increase in costs of living. Recent research from the USA suggests that the impact of growth in high-skilled businesses on individuals depends on whether they own their own home. Those that do, are able to capitalise on the increased productivity high-skilled exporters bring into a city through an increase in the value of their home. Those who do not, bear the costs of this increased productivity in the form of higher rents.7 Low-skilled people, who tend to be in low-paid jobs, are more likely to fall into the second category.

This suggests that creating job opportunities is a necessary, but not sufficient, condition when it comes to providing better economic outcomes for low-skilled people. The favourable indicators of economic performance for low-skilled people in stronger economies may, in fact, be the result of other low-skilled people being priced out of these cities. Policymakers in successful cities need to think carefully about the ability of low-skilled people to live in these economies when designing their inclusive growth strategies.