03The nature of the new graduate workforce

The final section looks at the characteristics of the new graduates’ labour market in Preston.

Half of new graduate workers in Preston studied elsewhere

Figure 16 brings together all graduates who decided to work in Preston on graduation to provide an overview of the nature of the graduate workforce in the city. 26 per cent of all workers were home-grown: growing up, studying and subsequently working in Preston. More than a quarter of workers had come to study in Preston and stayed for work. 29 per cent of new graduate workers had been attracted in from elsewhere.

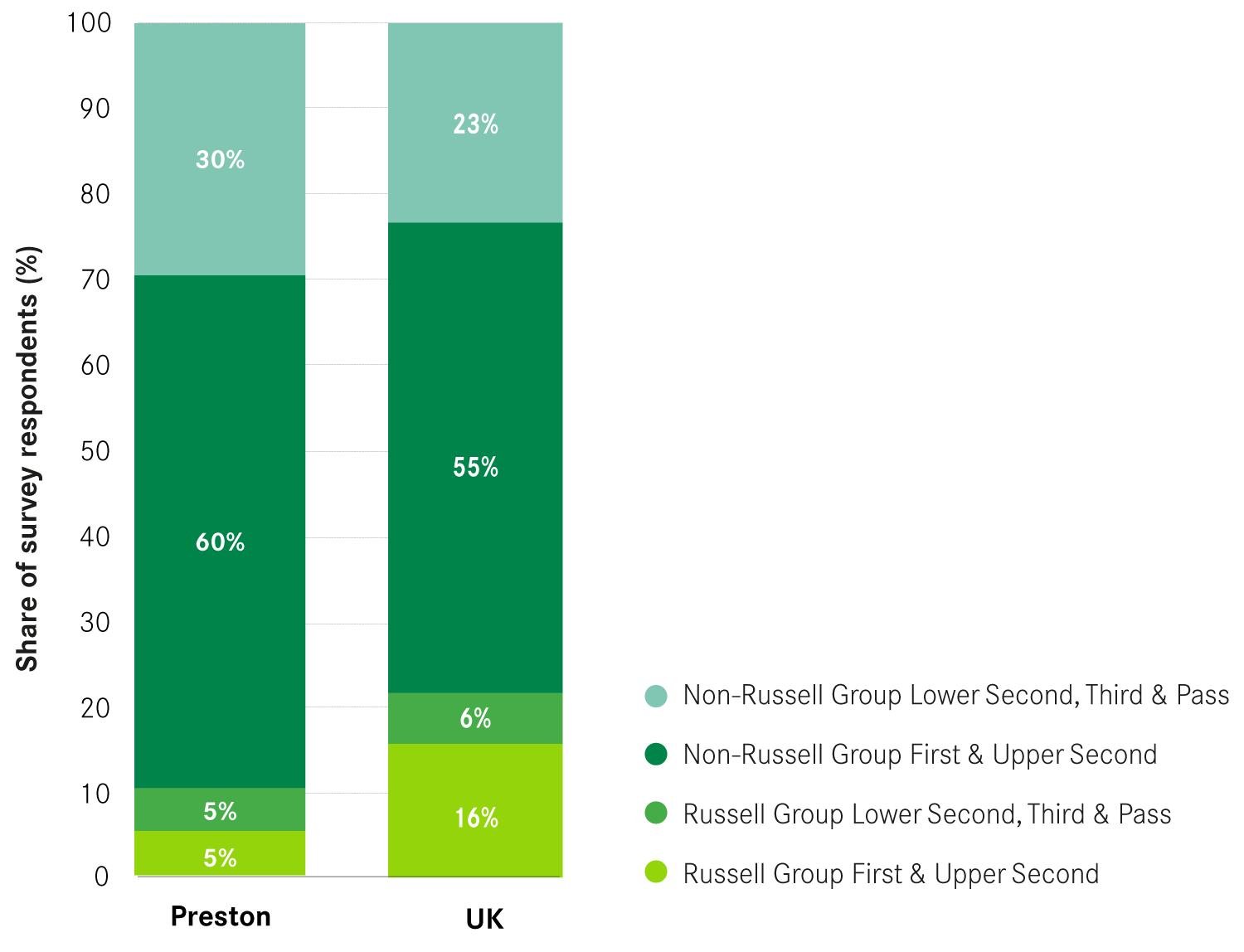

In terms of the class degree achieved, the composition of Preston’s graduate workforce is somewhat different from the one of the UK as a whole. Only 5 per cent of graduates working in Preston had a first or upper second class degree from a Russell Group University; for the UK as a whole the figure is 16 per cent. Meanwhile the city had a higher share of non-Russell Group with a first or upper second class degree.

Graduate wages in Preston are below the national average

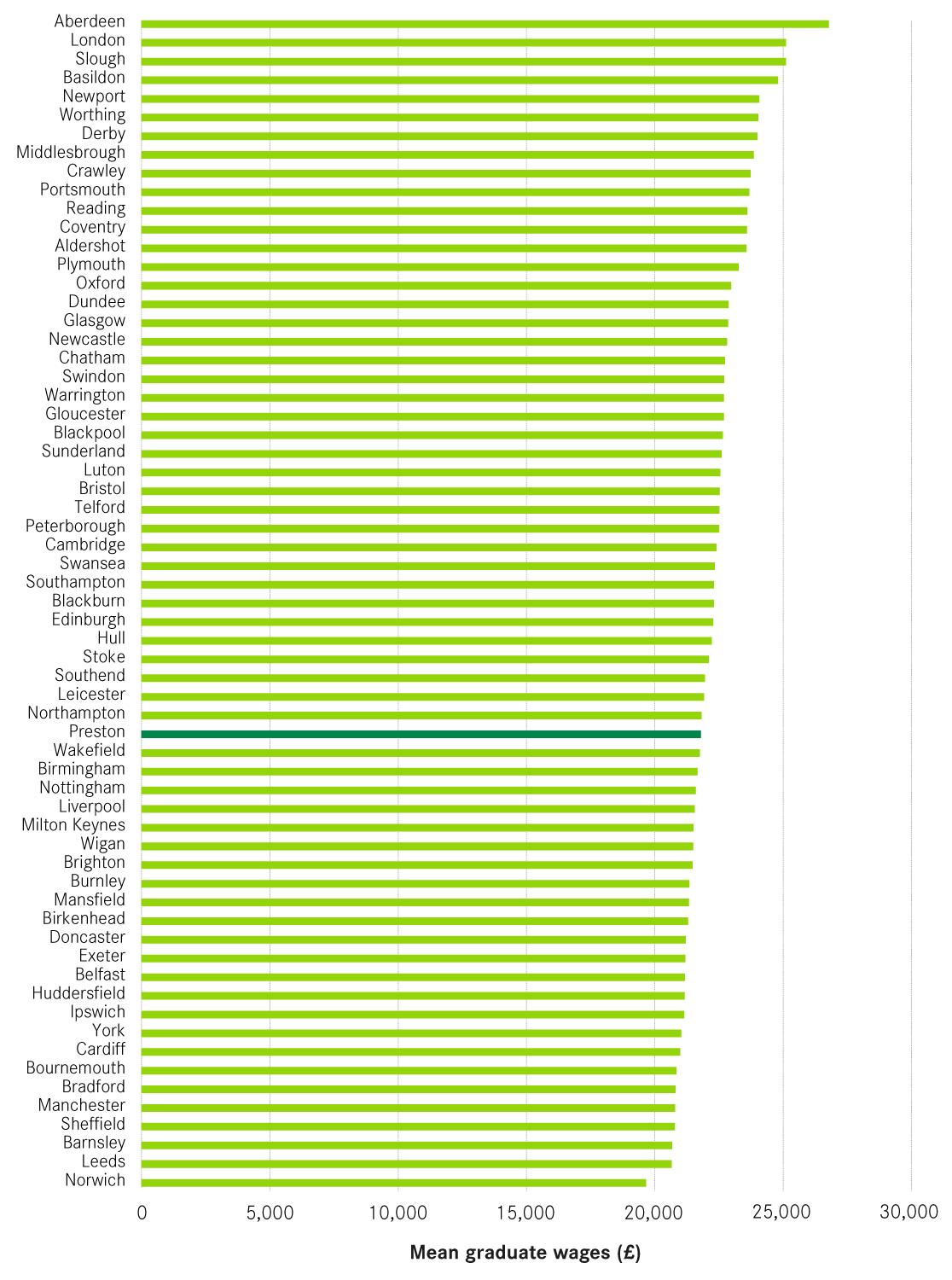

Graduates working in Preston earned on average £21,890 and this is the 39th highest graduate wage among UK cities as shown in Figure 18. However, analysis of UK graduates finds that graduates’ wages were not the main reason why graduates choose their employment location. Other factors such as the type of jobs available in that city and the opportunities for career progression were more important.

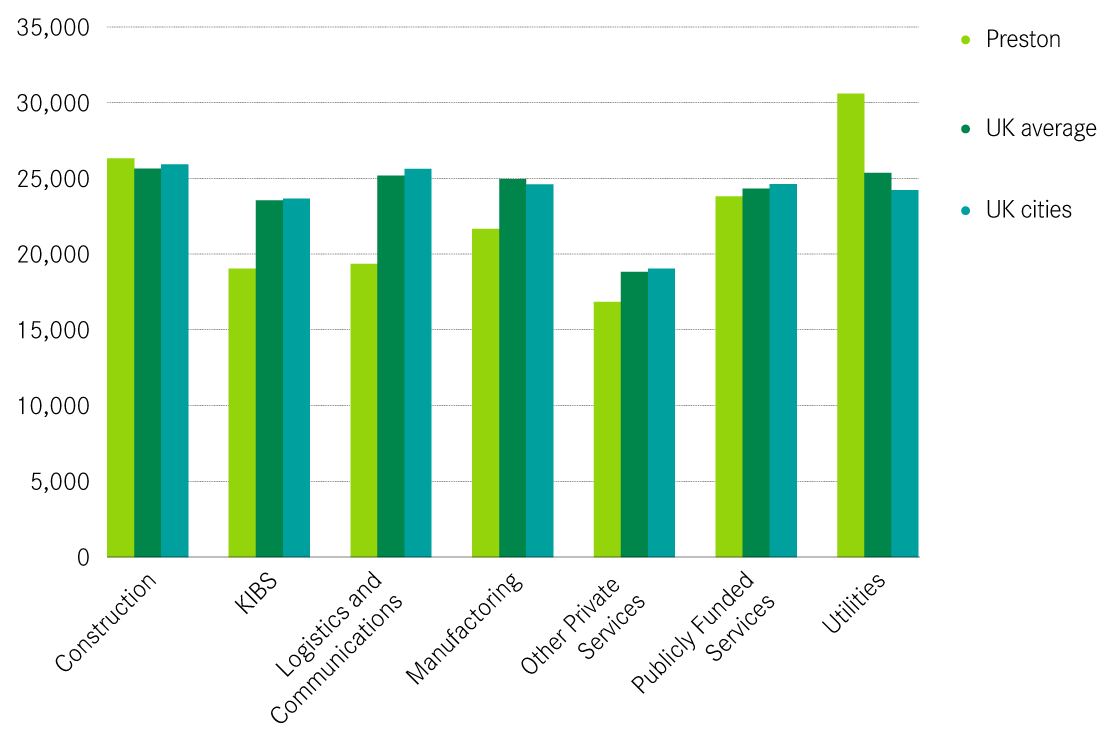

If we look at wages by sector, as shown in Figure 19, construction was the sector with the highest graduate wages. These are slightly higher than the national average graduate wage for this industry and the 14th highest among UK cities. However, graduate wages for those who worked in KIBS were substantially lower than the national average as well as the UK cities average.

The share of graduates in high-skilled jobs is below the UK average.

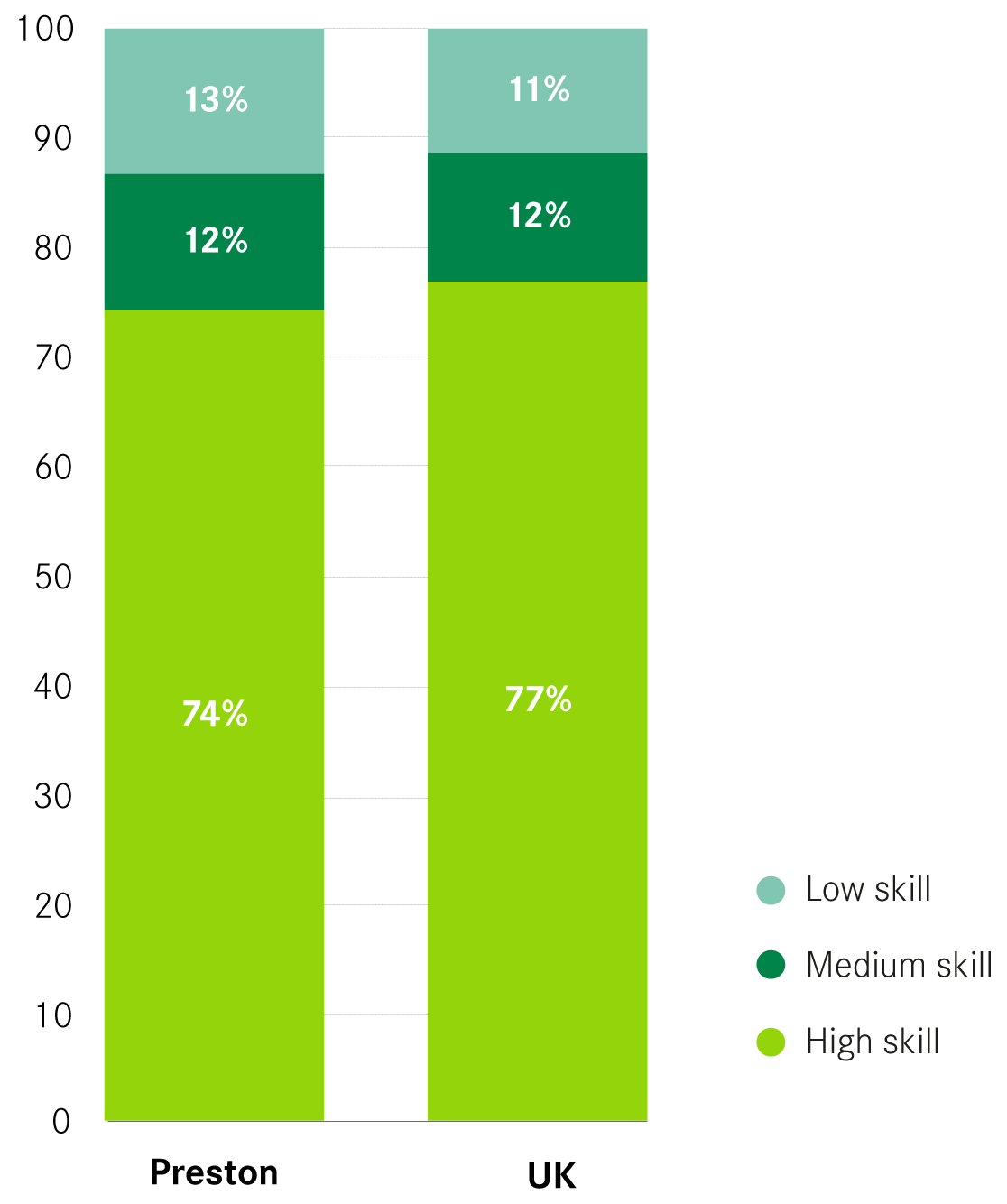

The type of jobs available to graduates in each location will be a major determinant of where they choose to work. Figure 20 shows that 74 per cent of new graduates in Preston were employed in high-skilled occupations but this is a lower proportion than for the UK as a whole. Slough, with 83 percent, had the highest share of graduates in high-skilled occupations. Preston’s share of new graduates in low-skilled jobs is higher than the UK average, and the 14th highest among UK cities. Oxford, with 6 per cent, had the lowest proportion of graduates in low-skilled jobs.

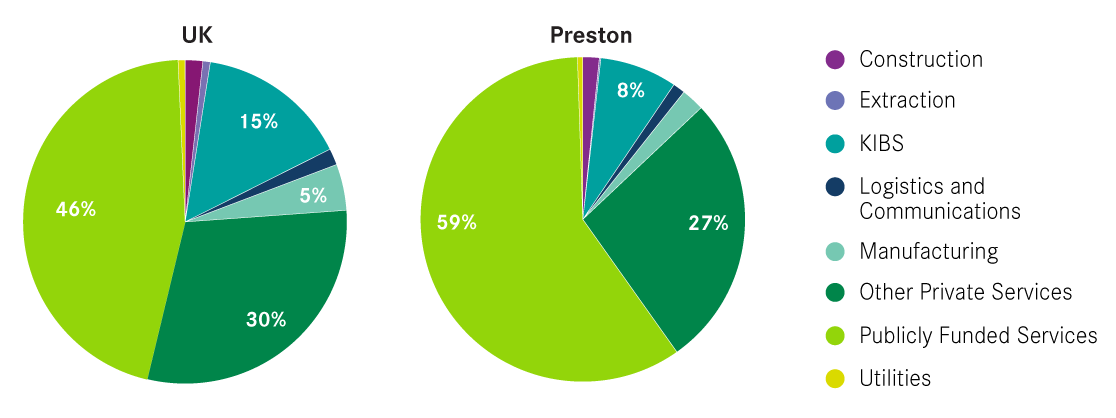

More than half of new graduates in Preston are employed in the publicly-funded services sector.

Figure 21 shows that 59 per cent of all graduates working in Preston were employed in publicly-funded jobs. This is considerably higher than the UK average and the 22nd highest among UK cities. At 8 per cent, the share working in private knowledge intensive business services (KIBS) was almost half the UK average and the 18th lowest among UK cities.

Looking at a finer industrial breakdown shows that in the publicly funded services, 28 per cent of all new graduates worked in health and 21 per cent in education.

Whereas the above analysis looks at the graduate workforce in Preston, the sectors employing new graduates from Preston outside of the city differs. Of those who studied in Preston but worked elsewhere 6 months later, 10 per cent worked in the KIBS sector, 48 per cent in the publicly funded services and 32 per cent in other private services. This suggests that one of the reasons why graduates move away is because certain sectors lack opportunities.

The type of graduate jobs available plays an important role in determining the size of the graduate workforce. The Great British Brain Drain found that graduate gains tend to be larger in cities with a smaller share of new graduates in publicly-funded jobs and a higher share in KIBS jobs.2 This suggests that in order to increase the size of the graduate workforce, Preston should promote growth in this sector.

How should policy encourage the growth of KIBS jobs?

High-skilled businesses require high-skilled workers. This means for a city to attract these types of businesses, they need to have a large pool of skilled workers to offer. There are two main things that policy can do to address this.

The first is to improve the skills of those people that have no or few formal qualifications. Educating someone to degree level, while a good thing in itself, is unlikely to have a great impact on Preston’s economy for the reasons outlined above. Instead, improving the skills of those with very poor qualification levels will make those individuals more productive, and because mobility of this group tends to be lower, have a subsequent impact on the stock of skills in the city.

The second is to better link those people with degree-level skills living around the city into the city itself. Of all the degree holders that live in the Lancashire LEP area, 71 percent live outside of the Preston PUA. Better linking this wider cohort into the city requires stronger transport connections with neighbouring areas, widening the pool of potential workers that businesses can choose from. The current development of new road schemes as part of the City Deal will improve access to Preston from other parts of Lancashire. Any further appropriate developments to further increase access into the city should also be considered upon the completion of these works.

Location is also important for high-skilled services businesses. As the work of Centre for Cities has shown, these jobs have increasingly preferred a city centre location.3 And as our previous work on Preston has demonstrated, the economic performance of its city centre has been weak in recent years.4 This means that reviewing the suitability of the commercial property available in the city centre, and reconfiguring existing stock and building new offices where appropriate should be done alongside required public realm improvements. Cities like Birmingham and Manchester that have managed to improve their city centres have also succeeded in attracting private sector jobs to their urban core.5

These steps should improve the attractiveness of Preston to KIBS businesses, which in turn would increase the number of graduate opportunities available in these businesses in the city.