01Introduction

Changes in culture and industry over the past two decades have put a greater value for firms firstly on knowledge, and secondly on ‘open innovation’ between companies, between industries and between institutions. This has strengthened the role of the university in city economies as a knowledge – and therefore value-generator.

In turn, there is an emergent consensus that collaborations between universities and high-growth firms are increasingly important for the national economy as innovation enables its growing firms to compete globally.

The UK is now a world leader in University-Business Collaborations

The UK has long had a thriving higher education sector; 10 of the global top 100 universities are in the UK including three of the top 10.1 However there has also been a persistent assumption that British universities have done badly compared with their international comparators (particularly Germany and the US) with regards to collaboration with businesses and universities.

Historically the evidence suggests that this may have once been true, but over the last five years the UK has jumped from 11th to 2nd in the global rankings for university – business collaboration.2 The Wilson Review 2012 reported that improvements over the last 10 years were largely due to a cultural change (from both firms and universities) towards open innovation and in particular the role of universities in providing high level skills and world class research.

This change in approach can also be attributed in part to the change of funding models that universities have undertaken over this period alongside wider government policies aimed to support collaborations. This shift has encouraged universities away from attempts to make professors ‘commercially-minded’, towards supporting the links that exist and improving the benefits of them.

UK cities are increasingly looking to universities as a hub to strengthen the links and attraction to – as well as productivity of – high-growth firms. Whilst there are many examples of cities doing this well, others struggle turning their ambition into reality.

This report is centred on case studies that – rather than showing best practice – highlight different ways of approaching the issue. Drawing the lessons from how cities, universities and businesses are delivering on their ambitions to drive productivity and innovation in their growing firms in different ways and at different scales. The paper sets the framework for these decisions and considers the ways in which cities can remove the barriers to high-growth firms collaborating with universities.

Key Questions and issues

Why cities?

Cities are where the vast majority of collaborations between firms and universities are happening. Cities are also best placed to establish and support these collaborations.

UK Universities are overwhelmingly in cities. Three quarters of UK Universities are based in cities, and over nine in 10 are within a 45 minute drive.3 Cities are home to 60 per cent of business births in the UK and 53 per cent of businesses. Cities are also most attractive for knowledge intensive jobs (73 per cent of KIBS jobs are in cities)4 and universities have been shown to add value to these sectors.5 With highly skilled labour forces, knowledge intensive jobs and the majority of universities located there, cities are well placed to bring together different skills sets, working relationships and financing risk profiles. It’s therefore cities where these relationships are formed and where the decisions about support should be made.

Why universities?

Universities have been actively pursuing different sources of income following the Browne report (2010) and the resulting cuts to HEFCE funding. But matching different skill sets and risk profiles can help both universities and businesses.

The increasing emphasis placed by universities on business collaboration6 has been partly attributed to changes in financial incentives. Primarily the shift in the approach of HEFCE to reflect discreet payments for knowledge exchange programmes and changes in Higher Education Innovation Funding.7 Alongside this, universities are increasingly under pressure to ensure they are working with businesses, in part to ensure their access to REF (Research Excellence Funding).

There has also been a wider cultural change towards open innovation – particularly in growing knowledge intensive industries, this has led to a higher demand for links with universities. Income from knowledge exchange between UK Higher Education Institutes and partners rose 45 per cent in terms of real value since 2003-04.6 Furthermore, for many sectors, commercial partnerships can improve both their research and teaching, attracting students increasingly conscious of career opportunities (also captured in the Key Information Set criteria).9

The Higher Education – Business Community Interaction (HE-BCI) survey showed that universities in the UK contributed £3.4 billion to the economy in 2011/12 through services to businesses – there is clearly significant value to be derived from these collaborations. Businesses that work with universities are usually motivated by the potential to innovate, develop networks and increase their market competitiveness.10 These relationships can range from contracting research, informal links or innovative research partnerships.

Box 1: Universities are key to their cities as direct employers and educators

Centre for Cities research found the largest direct impact from universities on the local economy is often the direct employment and money spent by its staff and students.11 Recent Universities UK research also found that the higher education sector is comparable in terms of direct employment to the legal services sector. Indirectly, the supply of highly skilled labour is the greatest driver of economic activity from a university.

Primarily, universities are teaching and research institutions. Throughout our research this has been re-iterated, policy makers looking to support links must recognise there is an opportunity cost to university staff and students’ time. Cities that are succeeding take unnecessary bureaucracy and administration away from professors and departments and break the barriers to collaboration that are identified by universities as well as their businesses.12

Why high-growth firms?

Public policy is increasingly targeting high-growth firms.

Many commentators, including NESTA, OECD, and The Work Foundation have called for a greater focus of Government funded business support on high-growth businesses. This is where policy can get ‘maximum impact’ rather than for example start-ups or university spin outs. Nascent start-up firms are unlikely to have to time or capacity to pursue innovative collaborations beyond their core business and are high risk when it comes to longer term innovation partnerships due to their failure rate. Whilst larger firms typically make decisions on a larger scale and independent of city level support for partnerships. This paper concentrates on growing firms rather than spin outs, the value of which is a source of much debate.13

Policy background – where have we been?

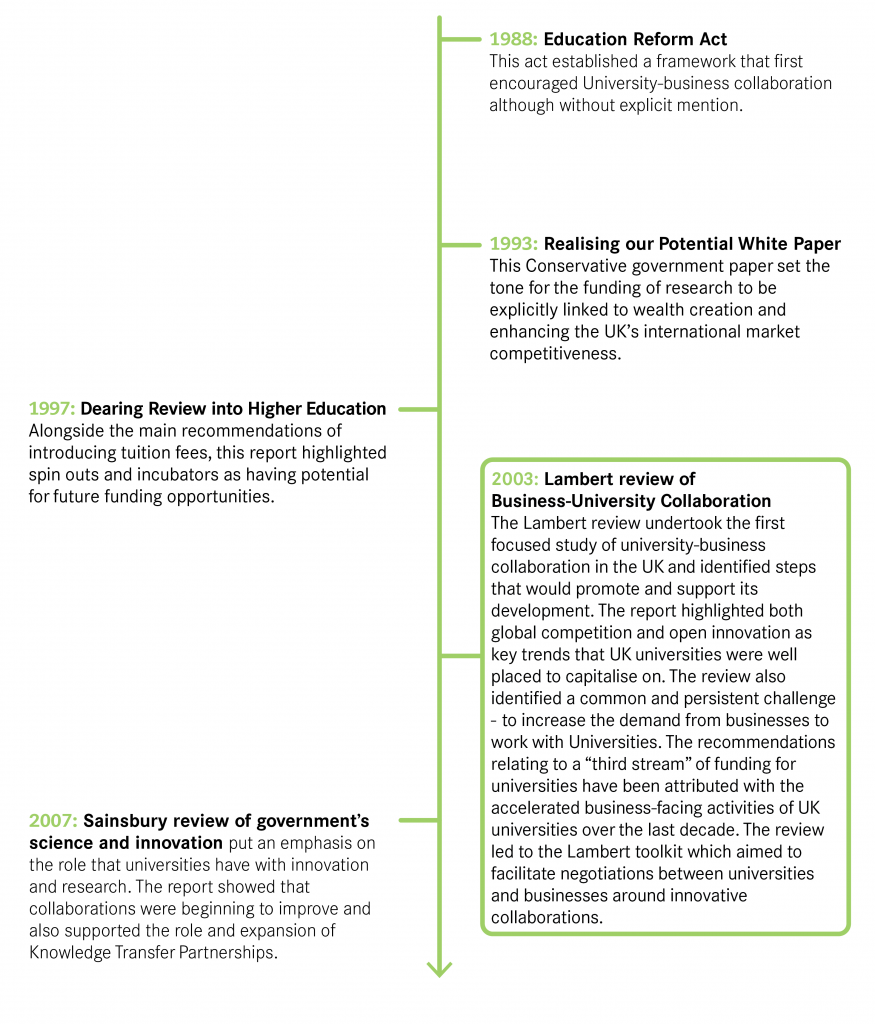

There is a significant recent history of policy in the UK aimed at getting universities to engage with businesses.14 This can be charted by the agenda setting reviews and acts over this period.

Policy context – where are we now?

With the broadly supportive BIS responses to the recent Wilson and Witty reviews, university and business collaboration appears to be an important and changing part of both the higher education and business innovation policy agenda.

Wilson Review of Business – University Collaboration, 2012

The Wilson review found university and business collaboration has improved hugely over the last 10 years in both the quantum and the quality of collaboration. It found that competition between universities for students, staff and research grants has led to more business relations, but collaboration between universities has also lead to successes.

The Government response was to provide The Key Information Set which gives prospective students information about different courses and institutions as well as their commercial activities.

The Wilson review also considered the specific needs of SMEs. It found that networking between universities and the business community is a critical component of an efficient innovation ecosystem, especially for highlighting opportunities in the SME sector to graduates.

The Government responded by creating the National Centre for Universities and Business (NCUB) which aims to strengthen collaboration between the UK’s higher education and business sectors. The NCUB attempts to maximise the support for growing fims and the value of innovative research and development from universities. The ongoing BIS Select committee is also evaluating the funding processes of collaboration and its role in local growth.15 Recent policy announcements regarding University Enterprise Zones and Catapult Centres are also discussed below.

Witty Review of Universities and Growth, 2013

The report supports the drive to ‘commercialise’ research outlined in the Government’s Industrial Strategy proposals. There is also support for greater collaboration between universities and SMEs, advocating “an enhanced third mission” for universities alongside research and education — to facilitate economic growth.

The review set out a key role for LEPs as well as cities in helping build networks and disseminate funding to support these collaborations.

The BIS response agreed that Local Enterprise Partnerships (LEPs) should put universities at the heart of their thinking and decision-making and should direct a large share of the £1 billion of European Structural and Investment Funds to universities.

It recommends that LEPs should collaborate beyond their own area with universities “whose cutting edge research generates economic activity through innovation” and should identify regional comparative advantages with the potential for economic growth.

The Government’s response is to create a new Advisory Hub for Smart Specialisation along the EU concept of identifying regions’ comparative advantages and promoting diversified growth in these industries.

The report’s headline proposal is for a £1 billion fund over the life of the next Parliament for ‘Arrow Projects,’ bringing together LEPs, universities and industrial and supply-chain partners to develop “new technologies through mobilising national clusters in fields offering significant international markets.”

The Government response was to “work with partners to realise The Arrow Projects”, which broadly follow the industrial strategies previously laid out and form a central part of the ‘sector not postcode’ approach advocated by the report.

University Enterprise Zones (UEZs)

The 2013 Budget announced a £15 million pilot programme for UEZs which aims to encourage universities role in local growth. The bidding was open to the eight core cities with the winning bids announced after the time of writing. The university enterprise zone is different to previous enterprise zones as they do not offer business rate discounts. However each UEZ will have support from UK Trade and Investment and a ‘clear offer’ from the relevant local planning authorities of simplified planning constraints where relevant.

UEZs offer ‘capital only’ spending which is expected to be added to by private funding and used for physical infrastructure investment. This model of university business collaboration may be helpful for some cities for example helping with funding for new incubator space (like Engine Shed in Bristol). However in limiting the fund to capital spending it excludes cities that may benefit from other expenditure (for example supporting existing networks). By limiting the pilot process to a single bid for each of the core cities, it might also have missed opportunities in the (albeit pilot phase) bidding process. The £5 million allocation for each site is to be spent over a 3-year period, which might also place an indicative limit on its use.

UEZs are designed to support high-growth firms in the government defined ‘industrial strategies’ or local growth initiatives. Whilst the focus on growing firms and comparative advantages is appropriate, there are risks. For example UEZs must ensure that they don’t become overly focused on certain sectors or firms (as shown with the Nokia Research Centre in Helsinki).

Although the University Enterprise Zones recognise the importance of place-specific policy and might be of use for some core city areas, the impact will remain limited by some of the bidding document’s parameters and re-visits some of the pitfalls of previous Enterprise Zones.16

Catapult Centres

Catapult Centres were established in 2012 with the aim to bring the UK’s businesses and scientists together on late-stage research and development in seven specific research areas located in physical centres. The Catapult model has been modelled in part on the Fraunhofer model (see later case study and comparison) and similarly to the Arrow Projects provide support for sectors rather than specific locales.

The aim is to commercialise ‘high potential’ ideas and products. It remains too early to properly evaluate their impact, the key to their success will be the buy-in from partners, as well as engaging high-growth firms and researchers beyond initial funding rounds.

Innovation vouchers

Innovation vouchers aim to enable small businesses to work with an external expert for the first time, gaining new knowledge to drive innovation and help businesses grow. This central aim has been welcomed by businesses and universities.17 To be eligible, firms must be working with an expert for the first time; it also must be a challenge that is in need of specific assistance.

The scheme benefits from being open to all SMEs (therefore not being too prescriptive) and a short and simple online application process. However there is a risk of balancing the burden of bureaucracy and allowing for ‘additionality’. Innovation vouchers must ensure that they are not regularly funding collaboration that would already be happening. Our conversations have also found that the value of the voucher (£5,000) is rarely enough to make an unviable piece of research viable.

What’s the role for cities in encouraging better collaboration between universities and high-growth firms?

Effective city level policies need to recognise that universities and high-growth firms are not homogenous groups.

Clearly universities have their own research and commercial business strengths. But a university as an institution also works differently to its departments and its staff who often operate almost independently of the organisation, especially in a commercial setting.17 High-growth firms also vary in their needs and expectations from collaborations. For some, there will be little benefit from collaborating at all, others will be intrinsically linked to departments or consult with professors to overcome discreet challenges. It is by using local knowledge, building networks and engaging key players that decision makers can find the right level of support for effective collaborations.

This means supporting their high-growth firms by removing the barriers they perceive to collaborate with universities, including those beyond their city boundaries. Cities need to adopt adaptable strategies for different sectors, different businesses and different relationships. The city’s role in these models can vary from being an agent of change (for example providing funding for Engine Shed in Bristol) to being a platform for delivering change (for example a centre of excellence in the Fraunhofer model).

Cities can ensure high-growth firms benefit from university collaborations in different ways by…

Supporting their long-term, large scale innovation systems through…

- Mapping and supporting industry and research strengths to enable businesses to work in close collaboration with a university or department, for example in the Fraunhofer model.

- Working with partners to build and form networks that benefit from the strengths of their universities and develop shared space for business and universities to co-locate. For example bio-tech and consultancy firms in Cambridge and its science parks.

Building scale to match business challenges and demand for innovation with universities’ research expertise through…

- Building innovation networks beyond their city boundaries around common interest groups, that deliver the scale of businesses and expertise to compete in global trade. For example Scottish food and drink producers brought together by Interface.

- Bringing universities and businesses together across city boundaries to access infrastructure otherwise beyond their reach. For example small businesses using the N8 High Performance Computer.

Identifying comparative advantages and removing the barriers to collaboration …

- Providing infrastructure funding and business support to improve firms’ productivity and create opportunities from a local academic strength. For example digital animation firms in Middlesbrough’s Digital City.

- Identifying funding opportunities that benefit locally successful industries, taking the long-term financial risk to expand support for a successful programme. For example Bristol’s Engine Shed which came from the SETSquared partnership.

There is no single blueprint that every city can or should implement. Cities that are making best use of university collaborations with high-growth firms are adopting flexible approaches that understand local conditions and remove barriers identified by their partners. And ensure that successful relationships are built upon and improved rather than stagnating or obstructing others.

Case Studies

The evidence suggests that by far the most prevalent prompt for successful collaboration is through individual relationships rather than through Technology Transfer programmes or university administration offices.19 Therefore the best approaches often rely on building the scale and networks of relationships that allow for these collaborations to happen, and reducing the barriers to future relationships rather than leaving city decision makers to choose and match firms with expertise or departments.

The value of these case studies is not as a definitive list of ‘best practice’ but is instead in analysing the different approaches and frameworks that cities have used to succeed.