02City monitor

There is considerable variation in the economic performance of cities and towns across the UK. The purpose of this chapter is to show the scale and nature of this variation by highlighting the performance of the 63 largest urban areas31 on 17 indicators covering:

- Population

- Productivity

- Employment

- Skills

- Wages

- Housing

- Business dynamics

- Digital connectivity

- Innovation

- Environment

For most indicators, the 10 strongest and 10 weakest performing places are presented.

Population

- In 2018, cities accounted for 9 per cent of land, but for 54 per cent of the UK population (36 million) and for 56 per cent of population growth between 2017 and 2018.

- The four biggest cities (London, Birmingham, Manchester and Glasgow) accounted for almost a quarter of the total UK population (24 per cent) and for 45 per cent of the total population living in cities.

- London alone was home to 15 per cent of the UK population and accounted for 23 per cent of all population growth in the UK between 2017 and 2018.

- Every city has experienced population growth compared to 10 years ago but, in eight cities, population declined compared to 2018. This is twice as many cities compared to 2017, when only four cities saw a decline.

Table 1: Population growth

Employment rate

- Overall, the UK employment rate continued to increase in 2019, and was up by 0.6 percentage points compared to 2018. The city average (73 per cent) was unchanged, and remained slightly lower than the national average (76 per cent).

- Thirty-four cities had employment rates below the national average. To bring these cities up to the current UK average, a further 513,600 residents in these places would need to find employment.

- Bradford, the UK city with the lowest employment rate in 2019 (66 per cent), would need 29,600 of its residents to find employment to reach the UK average. Birmingham remains the city with the highest deficit in absolute terms (-113,000) despite an increase in its employment rate (1.4 percentage points).

- Large cities tend to fare worse than smaller cities. Two of them – Birmingham and Liverpool – are among the cities with the lowest employment rate. Only Bristol features in the top 10 cities with the highest employment rate.

Table 2: Employment rate

|

Rank |

City |

Employment rate, Jul 2018-Jun 2019 (%) | Employment rate, Jul 2017-Jun 2018 (%) | Percentage point change |

| 10 cities with highest employment rate | ||||

| 1 | Oxford | 82.4 | 81.3 | 1.1 |

| 2 | Aldershot | 82.2 | 78.9 | 3.4 |

| 3 | Ipswich | 81.8 | 76.4 | 5.4 |

| 4 | Southend | 80.4 | 82.9 | -2.5 |

| 5 | Cambridge | 80.4 | 75.2 | 5.1 |

| 6 | Reading | 79.7 | 78.3 | 1.3 |

| 7 | Northampton | 79.5 | 76.5 | 3.0 |

| 8 | Preston | 79.4 | 82.8 | -3.4 |

| 9 | Bristol | 79.0 | 79.2 | -0.1 |

| 10 | Bournemouth | 78.9 | 76.5 | 2.4 |

| 10 cities with lowest employment rate | ||||

| 54 | Swansea | 69.9 | 67.7 | 2.2 |

| 55 | Luton | 69.8 | 69.7 | 0.1 |

| 56 | Sunderland | 69.7 | 71.0 | -1.3 |

| 57 | Liverpool | 68.6 | 68.4 | 0.2 |

| 58 | Blackburn | 68.4 | 64.2 | 4.2 |

| 59 | Burnley | 68.4 | 71.5 | -3.2 |

| 60 | Birmingham | 68.3 | 66.9 | 1.4 |

| 61 | Middlesbrough | 68.3 | 67.8 | 0.5 |

| 62 | Dundee | 66.8 | 65.1 | 1.7 |

| 63 | Bradford | 66.3 | 68.1 | -1.8 |

| United Kingdom | 75.5 | 74.9 | 0.6 | |

Unemployment benefit claimant count

- More than two-thirds (72 per cent) of those claiming unemployment benefits lived in cities in November 2019.

- The claimant count rate in cities is at 3.3 per cent, more than twice the average rate for elsewhere in the country and only 18 cities have a claimant count rate lower than the UK average of 2.6 per cent.

- None of the 10 cities with the highest claimant counts are in the North or Midlands, with Dundee being the only exception.

- Eight of the 10 cities with the lowest claimant counts are in the South, with York and Edinburgh being the exceptions.

Table 3: Unemployment benefit claimant count

|

Rank |

City |

Claimant count rate,

Nov 2019 (%) |

| 10 cities with the lowest claimant count rate | ||

| 1 | York | 1.3 |

| 2 | Aldershot | 1.3 |

| 3 | Exeter | 1.5 |

| 4 | Cambridge | 1.5 |

| 5 | Oxford | 1.9 |

| 6 | Edinburgh | 1.9 |

| 7 | Reading | 1.9 |

| 8 | Bristol | 2.2 |

| 9 | Portsmouth | 2.3 |

| 10 | Norwich | 2.4 |

| 10 cities with the highest claimant count rate | ||

| 54 | Newcastle | 4.5 |

| 55 | Liverpool | 4.6 |

| 56 | Dundee | 4.6 |

| 57 | Middlesbrough | 4.7 |

| 58 | Bradford | 4.8 |

| 59 | Blackburn | 4.8 |

| 60 | Sunderland | 4.9 |

| 61 | Blackpool | 5.0 |

| 62 | Hull | 5.3 |

| 63 | Birmingham | 5.5 |

| United Kingdom | 2.6 | |

Wages

- In 2019, the average weekly workplace wage in cities was £612, compared to the UK average of £571.

- Only 13 cities had wages above the UK average, with London’s average weekly workplace wage being 35 per cent above the national average.

- Derby maintains its position as the only English city not in the Greater South East in the top 10, while Southend maintains its position as the only city in the Greater South East to be in the bottom 10.

Table 4: Average workplace earnings

|

Rank |

City |

Wages, 2019 (av £ per week, 2019 prices) | Wages, 2018 (av £ per week, 2019 prices) | Real wages growth 2018-2019 (£ per week) |

| 10 cities with the highest weekly workplace earnings | ||||

| 1 | London | 768 | 768 | 0 |

| 2 | Slough | 731 | 660 | 71 |

| 3 | Aldershot | 707 | 662 | 45 |

| 4 | Reading | 678 | 684 | -6 |

| 5 | Derby | 668 | 638 | 29 |

| 6 | Cambridge | 656 | 671 | -15 |

| 7 | Milton Keynes | 651 | 623 | 29 |

| 8 | Aberdeen | 636 | 616 | 20 |

| 9 | Crawley | 617 | 655 | -38 |

| 10 | Oxford | 608 | 624 | -16 |

| 10 cities with the lowest weekly workplace earnings | ||||

| 54 | Preston | 489 | 514 | -25 |

| 55 | Leicester | 487 | 475 | 12 |

| 56 | Mansfield | 485 | 512 | -27 |

| 57 | Norwich | 484 | 478 | 6 |

| 58 | Stoke | 483 | 473 | 10 |

| 59 | Swansea | 478 | 478 | 0 |

| 60 | Wigan | 478 | 446 | 31 |

| 61 | Burnley | 467 | 492 | -25 |

| 62 | Huddersfield | 463 | 451 | 11 |

| 63 | Southend | 450 | 448 | 2 |

| United Kingdom | 571 | 566 | 5 | |

Business starts and closures

- Two out of three businesses (63 per cent) that started up in 2018 were located in cities. This has increased in recent years: in 2011, 58 per cent of business starts were in cities.

- Despite this, only 13 cities had a start-up rate higher than the UK average of 57 per 10,000 population.

- At the same time, 61 per cent of UK business closures occurred in cities in 2018.

- The three cities with the highest number of business closures – London, Manchester and Milton Keynes – were also among the top 10 cities for business start-ups.

- Liverpool, Southampton and Brighton had the highest churn rate – these cities saw the greatest difference between new businesses setting up and existing businesses closing.

Table 5: Business starts and closures per 10,000 population

|

Rank |

City |

Business start-ups per 10,000 population, 2018 | Business closures per 10,000 population, 2018 | Churn rate* |

| 10 cities with the highest start-up rate | ||||

| 1 | London | 105.0 | 84.9 | 3.0 |

| 2 | Brighton | 90.0 | 56.3 | 6.1 |

| 3 | Manchester | 82.1 | 76.7 | 1.1 |

| 4 | Milton Keynes | 81.0 | 60.9 | 3.6 |

| 5 | Northampton | 80.2 | 59.3 | 4.4 |

| 6 | Southampton | 80.0 | 52.9 | 6.4 |

| 7 | Luton | 74.7 | 56.3 | 4.6 |

| 8 | Liverpool | 73.8 | 49.3 | 7.0 |

| 9 | Slough | 72.8 | 56.0 | 3.5 |

| 10 | Reading | 67.2 | 57.7 | 1.8 |

| 10 cities with the lowest start-up rate | ||||

| 54 | Middlesbrough | 36.5 | 33.1 | 1.2 |

| 55 | Wakefield | 35.5 | 34.1 | 0.5 |

| 56 | Mansfield | 34.5 | 28.6 | 2.2 |

| 57 | Wigan | 34.5 | 30.7 | 1.3 |

| 58 | Dundee | 34.3 | 29.9 | 1.7 |

| 59 | Belfast | 33.4 | 29.3 | 1.2 |

| 60 | Stoke | 33.2 | 30.8 | 0.9 |

| 61 | Hull | 31.7 | 27.8 | 1.5 |

| 62 | Plymouth | 31.2 | 27.0 | 1.7 |

| 63 | Sunderland | 27.6 | 27.0 | 0.2 |

| United Kingdom | 57.3 | 50.5 | 1.5 | |

Business stock

- Cities were home to 56 per cent of all UK businesses in 2018.

- However, only 10 cities had a higher business stock per 10,000 population than the UK average (442).

- London alone accounted for 23 per cent of the total UK business stock and for 42 per cent of total cities’ business stock, far larger than Manchester and Birmingham (accounting for 4 per cent and 3 per cent of the total UK business stock respectively).

- London also ranked first for business stock per capita, with 677 businesses per 10,000 population.

Table 6: Business stock per 10,000 population

|

Rank |

City |

Business stock per 10,000 population, 2018 | Business stock per 10,000 population, 2017 | Change, 2017-18 (%) |

| 10 cities with the highest number of businesses | ||||

| 1 | London | 677 | 678 | -0.2 |

| 2 | Milton Keynes | 553 | 545 | 1.6 |

| 3 | Brighton | 551 | 526 | 4.6 |

| 4 | Reading | 539 | 541 | -0.4 |

| 5 | Warrington | 510 | 536 | -4.8 |

| 6 | Aldershot | 489 | 491 | -0.4 |

| 7 | Slough | 483 | 472 | 2.5 |

| 8 | Manchester | 474 | 463 | 2.4 |

| 9 | Northampton | 471 | 476 | -1.0 |

| 10 | Basildon | 465 | 464 | 0.1 |

| 10 cities with the lowest number of businesses | ||||

| 54 | Barnsley | 284 | 282 | 0.7 |

| 55 | Middlesbrough | 282 | 282 | -0.2 |

| 56 | Swansea | 282 | 265 | 6.2 |

| 57 | Stoke | 278 | 278 | -0.1 |

| 58 | Mansfield | 270 | 273 | -0.9 |

| 59 | Hull | 262 | 264 | -0.8 |

| 60 | Dundee | 254 | 252 | 1.0 |

| 61 | Plymouth | 247 | 250 | -1.0 |

| 62 | Sunderland | 229 | 234 | -1.9 |

| United Kingdom | 442 | 443 | 0.1 | |

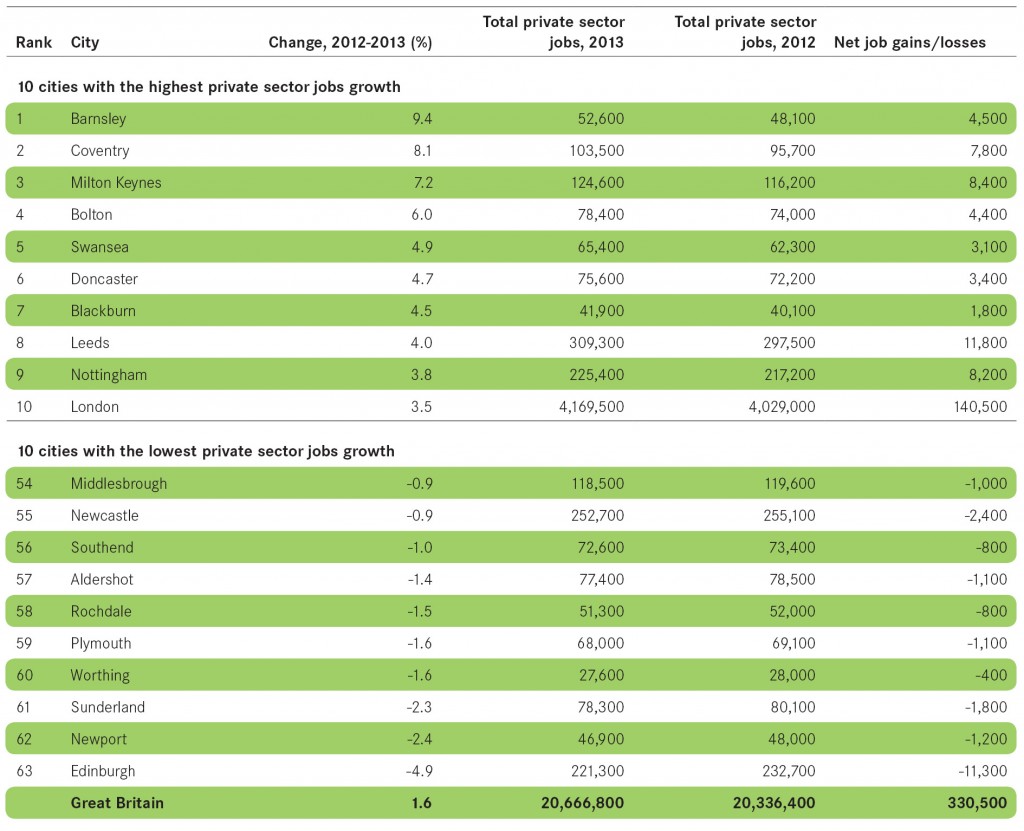

Private sector jobs growth

- Between 2017 and 2018, the number of private sector jobs increased slightly faster in cities (1.2 per cent) than the country as a whole (1.0 per cent).

- In 2018, 59 per cent of all private sector jobs were located in cities, and 70 per cent of the 190,500 jobs created between 2017 and 2018 were created in cities.

- Forty cities increased their number of private sector jobs compared to 2017, and 30 did so by more than the British average.

- Four of the cities with the highest private sector jobs growth in 2017 were amongst the cities with the lowest private sector jobs growth in 2018. These were Middlesbrough, Newcastle, Bradford and York.

Public and private sector jobs

- In 2018, the private to public sector employment ratio in Great Britain was 2.9.

- In general, the job market in cities tends to be more dominated by publicly-funded activities than the national average. Out of 62 cities, only 19 had private to public employment ratios above the British average.

- Crawley had the highest private to public sector ratio, with seven private- sector jobs for each public one. At the other end of the spectrum, Oxford had almost the same number of private and public sector employees, mainly the result of its universities.

Table 7: Ratio of private sector to publicly-funded jobs

|

Rank |

City |

Private to public ratio, 2018 | Private sector jobs, 2018 | Publicly-funded jobs, 2018* |

| 10 cities with the highest proportion of private sector jobs | ||||

| 1 | Crawley | 7.3 | 84,000 | 11,500 |

| 2 | Slough | 4.8 | 70,000 | 14,500 |

| 3 | Warrington | 4.4 | 111,000 | 25,500 |

| 4 | Swindon | 4.0 | 94,500 | 23,500 |

| 5 | Aldershot | 3.8 | 85,500 | 22,500 |

| 6 | London | 3.7 | 4,645,000 | 1,261,500 |

| 7 | Milton Keynes | 3.7 | 145,000 | 39,500 |

| 8 | Reading | 3.6 | 153,500 | 42,500 |

| 9 | Peterborough | 3.5 | 92,000 | 26,000 |

| 10 | Basildon | 3.4 | 67,000 | 20,000 |

| 10 cities with the lowest proportion of private sector jobs | ||||

| 53 | Liverpool | 2.0 | 212,500 | 107,500 |

| 54 | Gloucester | 1.9 | 42,500 | 22,000 |

| 55 | Plymouth | 1.9 | 72,500 | 38,500 |

| 56 | Exeter | 1.8 | 61,000 | 33,500 |

| 57 | Birkenhead | 1.8 | 66,500 | 37,500 |

| 58 | Swansea | 1.7 | 102,500 | 59,000 |

| 59 | Dundee | 1.6 | 47,000 | 30,000 |

| 60 | Cambridge | 1.5 | 65,500 | 43,000 |

| 61 | Worthing | 1.5 | 29,500 | 20,000 |

| 62 | Oxford | 1.1 | 63,500 | 59,000 |

| Great Britain | 2.9 | 22,952,000 | 7,862,500 | |

Innovation

- In total, there were about 7,800 patent applications in 2018. Of these, 48 per cent were in cities.

- The overall number of patent applications fell compared to the previous year. In 2018, there were on average 12 patent applications per 100,000 residents, an average of six patents fewer than in 2017.

- Cambridge continues to be the city with the highest number of published patent applications.

- The top 10 cities for patent applications accounted for 17 per cent of all applications in the country and for 35 per cent of all applications in cities.

Table 9: Patent applications published per 100,000 residents

|

Rank |

City |

UK patent applications published per 100,000 residents, 2018 |

| 10 cities with highest number of published patent applications | ||

| 1 | Cambridge | 148.1 |

| 2 | Coventry | 95.5 |

| 3 | Oxford | 64.5 |

| 4 | Derby | 61.0 |

| 5 | Aldershot | 39.0 |

| 6 | Aberdeen | 34.1 |

| 7 | Edinburgh | 31.6 |

| 8 | Gloucester | 24.0 |

| 9 | Bristol | 20.1 |

| 10 | Birkenhead | 19.9 |

| 10 cities with lowest number of published patent applications | ||

| 54 | Liverpool | 5.4 |

| 55 | Sunderland | 4.9 |

| 56 | Glasgow | 4.4 |

| 57 | Southend | 4.3 |

| 58 | Luton | 4.3 |

| 59 | Doncaster | 4.1 |

| 60 | Ipswich | 4.1 |

| 61 | Barnsley | 3.6 |

| 62 | Wakefield | 2.9 |

| 63 | Wigan | 2.6 |

| United Kingdom | 11.9 | |

Productivity

- In 2018, productivity, measured as GDP per worker, was higher on average in cities (£71,100) compared to the national average (£68,900). In addition to this, GDP per worker saw a greater average increase in cities, rising by 2.9 per cent compared to a 2.3 per cent national average.

- However, only 12 cities out of 62 had levels of productivity above the British average. With the exception of Edinburgh, all of them are in the Greater South East.

- In 16 cities, productivity per worker was at least 20 per cent lower than the national average. In Blackburn, it was almost 30 per cent lower than the national average.

Table 10: GDP per worker

| Rank | City | GDP per worker, 2018 (£) |

| 10 cities with the highest GDP per worker | ||

| 1 | Slough | 100,000 |

| 2 | London | 91,300 |

| 3 | Swindon | 86,800 |

| 4 | Milton Keynes | 84,800 |

| 5 | Reading | 83,800 |

| 6 | Worthing | 81,300 |

| 7 | Luton | 80,900 |

| 8 | Edinburgh | 75,100 |

| 9 | Ipswich | 75,100 |

| 10 | Basildon | 74,200 |

| 10 cities with the lowest GDP per worker | ||

| 53 | Newcastle | 53,500 |

| 54 | Huddersfield | 53,500 |

| 55 | Doncaster | 53,300 |

| 56 | Barnsley | 52,900 |

| 57 | Blackpool | 52,700 |

| 58 | Oxford | 52,200 |

| 59 | Dundee | 52,100 |

| 60 | Newport | 52,000 |

| 61 | Mansfield | 49,700 |

| 62 | Blackburn | 48,700 |

| Great Britain | 67,400 | |

High-level qualifications

- Cities are home to 58 per cent of the UK working-age population with a degree or equivalent qualification.

- However, the UK’s high-skilled population is concentrated in a few cities. The top 10 cities combined account for over 29 per cent of the UK’s high-skilled population (compared to 22 per cent of the working-age population).

- In 2018, 43 cities had a share of population with high-level qualifications lower than the UK average (39 per cent), less than in 2017, when 46 cities were below the national average.

- Scottish cities perform particularly well on this measure, and three out of four are now in the top 10 for share of population with high-level qualifications.

- Eight of the 10 cities with the lowest share of population with high-level qualifications do not have a university. Hull and Sunderland are in the bottom 10 despite having universities.

Table 11: Residents with high-level qualifications

|

Rank |

City |

Working age population with NVQ4 & above, 2018 (%) |

| 10 cities with the highest percentage of people with high qualifications | ||

| 1 | Oxford | 63.2 |

| 2 | Cambridge | 61.4 |

| 3 | Edinburgh | 58.8 |

| 4 | Reading | 53.8 |

| 5 | London | 52.1 |

| 6 | Aberdeen | 48.9 |

| 7 | York | 47.9 |

| 8 | Brighton | 47.2 |

| 9 | Cardiff | 46.8 |

| 10 | Glasgow | 46.7 |

| 10 cities with the lowest percentage of people with high qualifications | ||

| 54 | Southend | 26.9 |

| 55 | Burnley | 26.2 |

| 56 | Barnsley | 25.8 |

| 57 | Wakefield | 25.4 |

| 58 | Peterborough | 25.1 |

| 59 | Sunderland | 25.0 |

| 60 | Hull | 24.2 |

| 61 | Basildon | 23.0 |

| 62 | Doncaster | 22.6 |

| 63 | Mansfield | 20.3 |

| United Kingdom | 39.2 | |

No formal qualifications

- Cities were also over-represented for people with no qualifications, although the share of people with no qualifications living in cities has slightly decreased compared to last year, from 59 to 58 per cent.

- Despite accounting only for 10 per cent of the UK’s overall working-age population, the 10 cities with the highest share of population with no qualifications account for 15 per cent of all the national total.

- Some cities have very polarised skills profiles: Glasgow had the 10th highest share of population with high qualifications but also the ninth highest proportion of population with no qualifications. Similarly, Dundee ranked 12th in terms of high qualifications but also had a high share of population with no formal qualifications (11 per cent).

Table 12: Residents with no formal qualifications

|

Rank |

City |

Percentage working age population with no formal qualifications, 2018 (%) |

| 10 cities with the lowest percentage of people with no formal qualifications | ||

| 1 | Bristol | 4.1 |

| 2 | Exeter | 4.3 |

| 3 | Gloucester | 4.9 |

| 4 | Southampton | 4.9 |

| 5 | Bournemouth | 5.1 |

| 6 | Plymouth | 5.2 |

| 7 | Crawley | 5.2 |

| 8 | Norwich | 5.3 |

| 9 | Reading | 5.4 |

| 10 | York | 5.5 |

| 10 cities with the highest percentage of people with no formal qualifications | ||

| 52 | Mansfield | 11.8 |

| 53 | Glasgow | 11.9 |

| 54 | Blackburn | 12.4 |

| 55 | Middlesbrough | 12.5 |

| 56 | Luton | 13.2 |

| 57 | Birmingham | 13.3 |

| 58 | Bradford | 13.8 |

| 59 | Leicester | 14.6 |

| 60 | Belfast | 15.9 |

| 61 | Burnley | 19.6 |

| United Kingdom | 8.0 | |

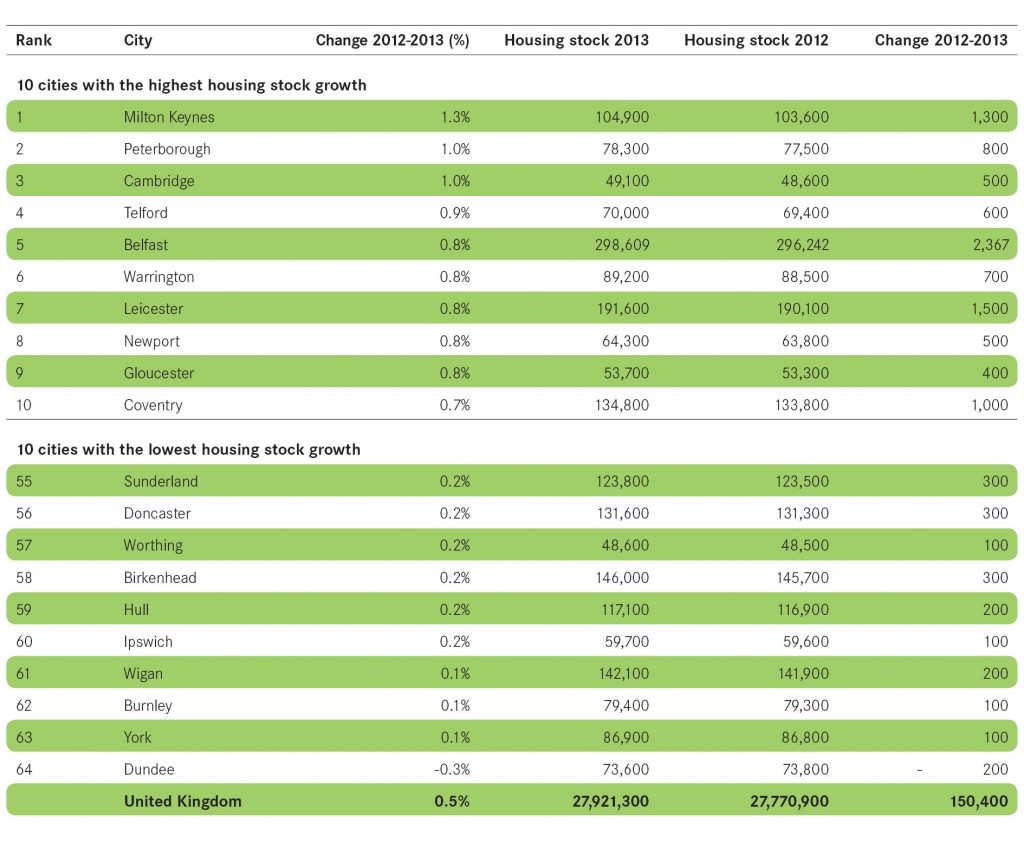

Housing stock growth

- In 2018, cities accounted for 52 per cent of the UK’s housing stock, but only for 49 per cent of new dwellings between 2017 and 2018.

- Housing stock growth exceeded the UK average in 20 cities only.

- For the third year, Cambridge is the city with the highest growth in housing stock and the city now has 16 per cent more homes than it did in 2008.

- In absolute terms, London is the city that built the most (36,700) new houses. However, this represented a housing stock growth of 0.9 per cent, ranking London only 22nd nationally.

House prices

- House prices in Great Britain increased on average by 0.5 per cent compared to 2018, with 33 cities seeing an increase.

- In 2019, house prices in London (£592,900) – the most expensive city – were almost twice the national average (£281,000), while house prices in Burnley (£106,800) – the least expensive city – were less than half the British average.

- The most expensive cities are not necessarily those building the most. Basildon, Brighton and Oxford are among the top 10 most expensive cities, but have some of the lowest housing stock growth in the country. In contrast, Cambridge, Reading and Slough are also among the most expensive places, but they lead the table for house building.

Table 14: House price growth

Housing affordability

- In 2019, on average, house prices in Britain were 4 times the annual salary of residents. This is slightly more affordable than the previous year, where the affordability ratio was 9.8.

- In total, only 15 out of 62 cities were less affordable than the British average.

- Only 18 cities have become more affordable over the last decade. However, all of them were already among the most affordable places 10 years ago.

Table 15: Housing affordability ratio

Digital connectivity

- The share of UK premises that had access to ‘ultrafast’ broadband (>100 Mbps) increased from 56 per cent in 2018 to 59 per cent in 2019.

- In 54 out of 63 cities, the proportion of properties with access to ultrafast speeds exceeded the UK average.

- Milton Keynes and Aberdeen experienced the largest growth in properties with access to ultrafast broadband (23 and 21 per centage point increases respectively).

- While there is variation in the coverage of ultrafast broadband (>100 Mps), the next level down in speed, ‘superfast’ broadband (>30 Mbps), is more consistently available, with all cities having at least 90 per cent of their properties covered by ‘superfast’ broadband.

Table 16: Premises achieving ultrafast broadband speeds

| Rank | City | Properties achieving ultrafast broadband, 2019 (%) |

| 10 cities with the highest ultrafast broadband penetration rate | ||

| 1 | Hull | 98.7 |

| 2 | Luton | 95.4 |

| 3 | Worthing | 94.9 |

| 4 | Belfast | 94.4 |

| 5 | Brighton | 93.6 |

| 6 | Cambridge | 93.5 |

| 7 | Dundee | 93.3 |

| 8 | Portsmouth | 93.1 |

| 9 | Plymouth | 92.2 |

| 10 | Ipswich | 91.7 |

| 10 cities with the lowest ultrafast broadband penetration rate | ||

| 54 | Huddersfield | 63.2 |

| 55 | Sunderland | 58.2 |

| 56 | Newport | 58.1 |

| 57 | Milton Keynes | 55.2 |

| 58 | Sheffield | 53.3 |

| 59 | Southend | 49.4 |

| 60 | Barnsley | 49.3 |

| 61 | Wakefield | 44.7 |

| 62 | Doncaster | 44.6 |

| 63 | Aberdeen | 23.3 |

| United Kingdom | 58.8 | |

CO2 emissions

- In 2017, cities accounted for 54 per cent of the UK population but for only 45 per cent of the UK’s total CO2 emissions.

- Average UK emissions per capita in 2017 totalled 5.3 tonnes (down from 5.5 tonnes in 2016), but the city average was lower at 4.5 tonnes.

- Swansea and Middlesbrough are significant outliers, emitting far more than the national average. However, Middlesbrough has seen a fall in its emissions (down 8 per cent compared to 2016), while emissions in Swansea increased by 3 per cent compared to 2016.