00The year to re-establish the urban voice

Brexit has completely dominated politics over the last 12 months. This can’t go on if we are to improve the economic opportunities available to people up and down the country.

2018 will not go down as a good year for domestic policy in the UK. Politics has been dominated by Brexit, leaving little parliamentary and civil service time and brain power, and very few newspaper column inches devoted to improving the poor economic performance of certain parts of the country.

The irony is that the focus on Brexit has drowned out any policy that would help improve the economies of those places that voted to leave. The Brexit vote, and the geography of it, sent out a clear message. Sadly in the aftermath, those listening have not used it to improve the lives of those who made the call but instead used it to trigger political jostling and in-fighting in Westminster.

This paralysis has left cities in a difficult position. The very centralised nature of the UK, even after recent moves towards greater devolution, leaves cities with limited tools to get on and improve their economies when central government is absent. The contrast of this to the USA is particularly stark. While American cities have got on with the job of tackling climate change or improving their economies in spite of the goings on in the White House, the lack of freedoms and flexibilities means that such actions aren’t as feasible here.

This is compounded by the effect that the paralysis has had on decisions that have an impact on the ability of cities to plan. The devolution agenda has all but stalled since 2016. The social care green paper has been delayed a number of times. And we still have no clarity on what the Shared Prosperity Fund – the fund that will replace EU monies after Brexit – will look like.

Added to this, our recent survey of city leaders revealed that 84 per cent of them did not believe their needs were represented on the national scale, while fewer than a third said they had good relationships with either civil servants or national ministers.1 No doubt the recent merry-go-round of ministers in cabinet has done little to help this.

The result is that cities are left in limbo. They have some control over policies, but much more limited than their international counterparts. Most feel like they don’t have a voice in national government. And they have little clarity on what future funding looks like.

In what little room there has been for political debate on domestic issues, much of this has been framed in terms of ‘left behind’ places. In recent months left behind has become synonymous with towns, with sections of both the left and the right of the political spectrum suggesting that policy has been too focused in recent years on cities to the detriment of towns.

Any discussion and debate about the geography of the economy is very welcome. Too much discussion is grounded in the concept of the national economy only, when the reality is that the national economy is a catch-all term for many hundreds of economies across the country. But for this discussion to be productive it must take place in the context of how and why the economy concentrates in specific places if it is to help improve the economic opportunity available to people up and down the country.

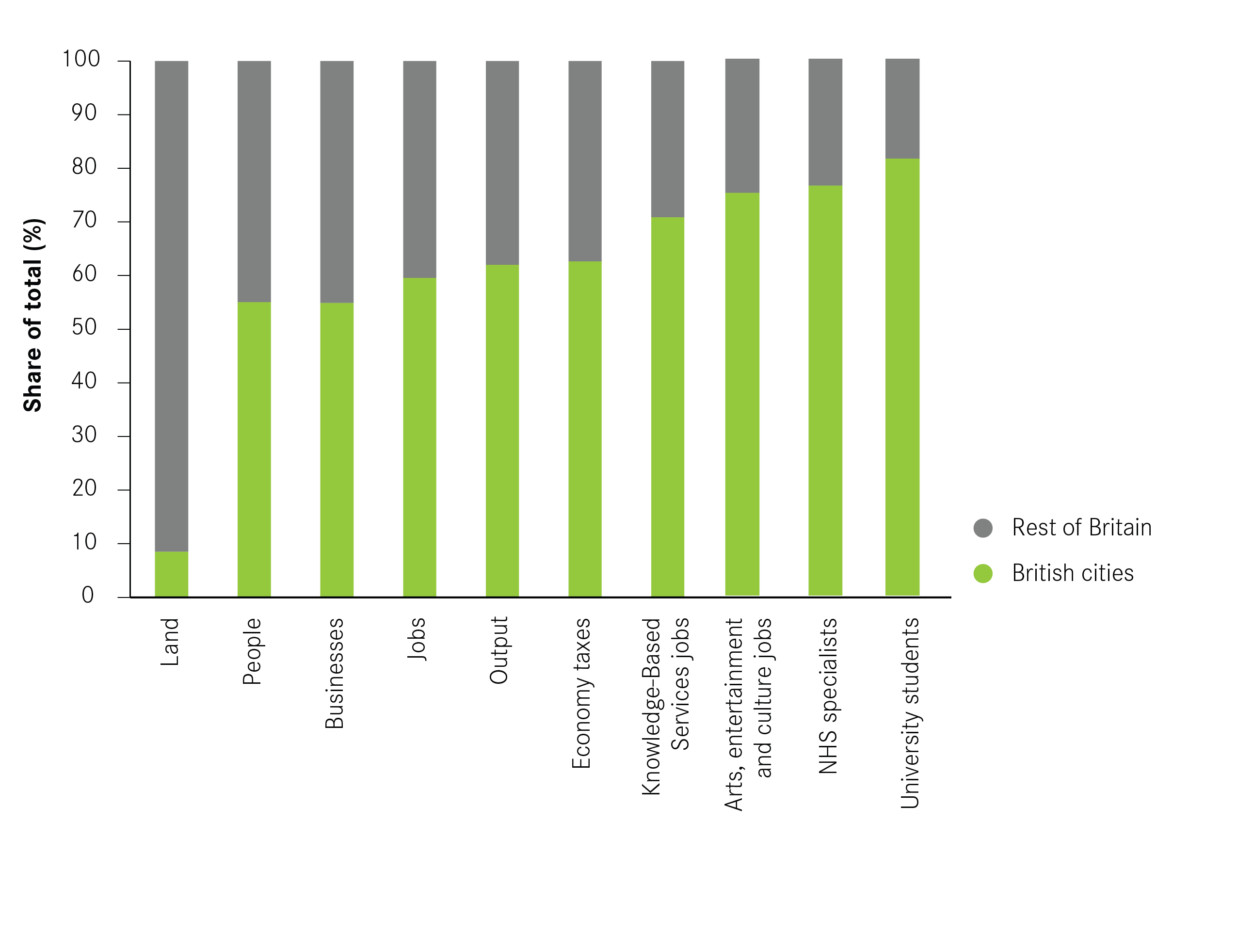

Cities account for a large part of the economy. Despite covering just 9 per cent of land, British cities account for 54 per cent of the population, 63 per cent of economic output and 71 per cent of knowledge services jobs. This concentration of the UK economy in specific places occurs because of the benefits that cities provide – namely access to lots of workers and proximity to other businesses.

And their role goes beyond direct economic links. Because of their scale, they are able to both support a greater number of specialisms and provide a wider range of services. For example, in terms of specialisms in healthcare and education, 76 per cent of NHS consultants practised in English and Welsh cities in 2018, and 81 per cent of university students studied in British cities in 2013/14 to 2014/15, benefiting residents beyond city boundaries.

Meanwhile, because of the size and density of markets that they provide, cities were home to three-quarters of all employment in creative arts and entertainment activities in 2017, the activities of which are enjoyed by city dwellers and non-city dwellers alike.

What is crucial within these figures though is that, as Cities Outlook has long shown and contrary to some current opinion, not all cities perform well. Despite their scale, many of the biggest cities punch below their weight. As the Data Monitor chapter shows, cities such as Manchester, Birmingham, Liverpool and Sheffield lag the national average on productivity and a range of other indicators, when they should be leading it.

This is a huge problem for these cities. But it is also bad for the surrounding areas of these cities too. Centre for Cities’ research in 2018 showed that on average, employment outcomes for people living in towns located close to successful cities had better outcomes than those located close to poorly performing cities.2 As shown in Figure 2, those towns close to highly productive cities tend to have fewer residents either unemployed or claiming long-term benefits.

This occurs for two reasons. The most obvious is through commuting links. In total 22 per cent of working people living outside of cities worked in one in 2011, showing that cities play an important role in providing work (and particularly high-skilled work) for those living beyond their borders. Clearly weaker cities are less able to provide these opportunities

The second reason is that cities also influence the ability of surrounding towns to attract in business investment in their own right. Those towns close to successful cities tended to have a higher share of high-skilled businesses located in them, than those close to less successful ones.

To ignore these links, and to ignore the differing roles that different parts of Britain – be they cities, towns or more rural areas – play in the national economy is to misunderstand an important part of how the economy functions. To mistakenly divert policy attention from cities would not only be bad for the city – it would be bad for the surrounding towns too. And crucially, this ultimately would be bad for the national economy.

In or out of the EU, for the UK economy to be more prosperous it needs its cities to make a larger contribution than they currently do. Policies such as city deals and devolution to city regions between 2010 and 2016 were welcome progress. The lull since cannot be allowed to persist – there needs to be a renewed focus on improving the economies of underperforming cities in particular when attention is given to domestic policy once more.

The all-encompassing coverage of Brexit has even diverted attention away from one of the most contentious domestic policies of recent times – public sector austerity. But with the Spending Review looming this year, 2019 cannot be a vacuum for domestic policy in the way that 2018 has been. The next chapter looks at how austerity has played out across cities, and what this means for both the forthcoming Spending Review and Fair Funding Review.

Box 1: Defining cities

The analysis undertaken in Cities Outlook compares Primary Urban Areas (PUAs) – a measure of the built-up areas of a city, rather than individual

local authority districts or combined authorities. A PUA is the city-level definition first used in the Department for Communities and Local Government’s State of the Cities report. The definition was created by Newcastle University and updated in 2016 to reflect changes from the 2011 Census.

The PUA provides a consistent measure to compare concentrations of economic activity across the UK. This makes PUAs distinct from city region or combined authority geographies. You can find the full definitions table and a methodological note on the recent PUA update.