011. Cities Outlook 2015

The year for cities

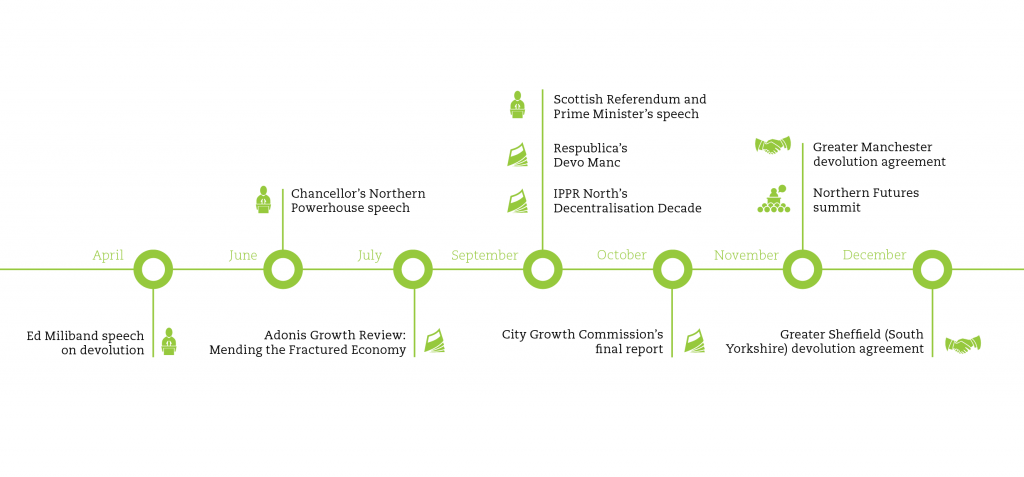

As the General Election looms, 2014 saw each of the three main political parties engage in a ‘race to the top’ on cities policy and devolution. The Chancellor’s commitment to build a ‘Northern Powerhouse’ – illustrated by the recent devolution deal with Greater Manchester – Labour’s pledge to boost decentralised funding to the tune of £30 billion, and the Liberal Democrats’ proposals for ‘devolution on demand’, all indicate that whoever wins in May 2015, the political and economic centralisation that has set the UK apart from the majority of its western peers may be about to change.

Alongside the moves from all major political parties to sign up to the idea of more devolution to UK cities and regions, there has also been a flurry of research looking at city growth and devolution, including IPPR North’s Decentralisation Decade1 and the RSA’s City Growth Commission.2

Cities and devolution have risen up the agenda over the last 12 months in response to three issues: politics, the economy and public finances.

Politically, much of the recent impetus has been driven by the fallout from the Scottish Independence Referendum. Even before the first vote had been cast, Westminster had made a series of promises to Scotland around greater devolution in the event of a ‘no’ vote. This unsurprisingly raised questions about what might follow in terms of devolution to and within England.

And it was most telling that, in his speech in the immediate aftermath of the referendum result, David Cameron committed to looking at “how to empower our great cities”3 in response to the West Lothian question.

Economically, there has been a growing recognition that cities matter to the future performance and shape of the national economy. This recognition was reflected by George Osborne setting out his vision of a ‘Northern Powerhouse’ and Nick Clegg launching ‘Northern Futures’.

From a public finance perspective, there is an increasing realisation that future reductions in public sector expenditure will be impossible to deliver without changing the way public services are designed and delivered, and this requires more to be done at the local level.

The response to these developments was the deal struck between the Chancellor and Greater Manchester to devolve significant powers and funding down to the city-region. In exchange for Greater Manchester creating a directly elected mayor to work in partnership with the combined authority, a series of London-style powers will be devolved, including powers over transport, planning, housing, police and skills. This announcement marked a significant moment for the devolution agenda and will result in a big shift in power from the centre to the city, with the hope of more to come.

In the last few weeks of 2014 a further devolution deal, albeit not as comprehensive, was struck between central government and Greater Sheffield.

The imperative now is to turn these deals into action. Too often in the past, good policy announcements have fallen at the hurdle of bureaucratic detail. With the backing of the Chancellor and the Deputy Prime Minister this looks less likely, but sustaining the momentum will be vital to ensuring these deals deliver the economic prosperity and public service reform they promise and the country needs.

Growing the economy and reducing the deficit

The last 12 months have seen the national economic recovery gather pace. Seven years on from the start of the recession, the UK economy is now 2.7 per cent larger than it was at its pre-recessionary peak and there are now 1.3 million more people in employment.4

As has been well documented, the recovery in employment has been much stronger than the recovery in output. This has meant that wages have been squeezed.

This has had two implications. Firstly, it has put a squeeze on living standards: wages, when accounting for prices, are still 12.6 per cent lower now than they were at the start of 2008.5 Secondly, it has put a further squeeze on public finances. Poor wage growth has meant that tax revenues have not increased as quickly as had been hoped.5

Regardless of which party wins the election in 2015, reducing the deficit poses further challenges for national government and for cities, but it also presents opportunities. Given the scale of the challenge, significant spending cuts and efficiency savings will be required, and this will only be feasible if there is a big change in the way that the state operates.

Devolving power to cities can help in two ways. Firstly, it can reduce the level of duplication in the system by better coordinating the different parts of the public sector that operate within a city. Secondly, it can allow cities to tailor policy and prioritise resources to more effectively address the challenges that they face.

But spending cuts and efficiency savings are unlikely to be enough. Cities not only have the potential to help reduce the deficit, they are also a means to achieve growth.

Covering just 9 per cent of land, cities account for 54 per cent of population, 60 per cent of jobs and 63 per cent of national output. And they are also more efficient, producing 19 per cent more output per worker than non-city areas and 27 per cent fewer carbon dioxide emissions.

In the year ahead the political conversation needs to be focused on how to support growth as well as on how to reduce the deficit, and both should have cities at their heart.

This year’s Outlook

The announcements made in late 2014 mark the latest staging point in what has been a 10-year conversation about cities and devolution.

Over this period the national economy has grown strongly, declined sharply and grown again, and the three main political parties have been in power. During this time all of them have explicitly attempted to boost growth in the regions, introducing a range of policies to help them support economic development outside London and the South East.

With the next election now only months away, and with each of the major parties pledging to support, empower and invest in UK cities should they win, the next chapter reflects on the performance of city economies over the last 10 years. It looks at the approach of policy during this period, and what this means for the future direction of cities policy.

Box 1 The use of Primary Urban Areas (PUAs)

The analysis undertaken in Cities Outlook compares cities’ Primary Urban Areas (PUAs) – a measure of the built-up areas of a city, rather than individual local authority districts.

A PUA is the city-level definition used in the Department for Communities and Local Government’s State of the Cities Report. It is useful as a consistent measure to compare cities across the country and we have used it since the first edition of Cities Outlook in 2008.

It is worth noting that, as is the case with almost every definition of geographic units, PUAs are imperfect and fit some areas better than others. Hull and Cambridge PUAs, for example, are slightly under-bounded. Some cities with substantial populations, such as Colchester, never made it into the PUA definition. And Manchester PUA is smaller than Greater Manchester, which also includes Rochdale, Bolton and Wigan PUAs.

PUA data only exists for English cities; for Welsh and Scottish cities we have used local authority data with the exception of tightly-bounded Glasgow, where we have defined the city as an aggregate of five Local Authorities: Glasgow City, West Dunbartonshire, East Dunbartonshire, East Renfrewshire and Renfrewshire. Belfast is defined as the aggregate of Belfast City, Carrickfergus, Castlereagh, Lisburn, Newtownabbey and North Down.