05How have political choices deepened wealth inequality across cities?

Although policies such as social housing and housing benefit mitigate the costs of housing shortages to low-income households across cities, other government policies contribute to, and deepen, inequality. These policies do not currently take into account the role of urban economies and shortages in shaping housing wealth, and, as such, struggle to achieve the competing objectives of both inexpensive housing costs and growing housing wealth for homeowners.

The planning system creates housing shortages

The housing shortages shown above are ultimately caused by how the English and Welsh planning systems ration land for development in and around cities.14 Measures such as the green belt, conservation areas, sightlines and height limits in cities, and the control of development through the planning permission system all decouple the supply of housing from local demand and its price signals, as evidenced earlier in Figure 4 and Figure 5.

The result is predictable in that the point of these policies is to reduce development, but the effect is to make the future supply of housing unpredictable and unresponsive to demand for new housing. Requiring every development to receive an explicit ‘yes’ from the local authority through planning permission means supply is capped at the rate at which the local authority

grants permissions.

The objective of the planning system should be to provide public goods and reduce negative externalities, not to reduce development. Enhancing urban mobility as cities grow, connecting new homes and employment spaces with existing infrastructure, and identifying changing demand for public services are all some of the crucial responsibilities planning has within local economies. These can all be achieved under a planning system in which the supply of housing is more responsive to local demand.

When controls on development have been reduced, supply has been driven by demand. The 2013 introduction of Permitted Development Rights (PDR) to allow offices to be converted into housing without local authority planning permission saw housing supply increase in expensive cities.

From 2015 to 2017, 48 per cent of all new housing in Crawley was delivered through PDR office conversions, as was 35 per cent in Basildon and 34 per cent in Slough. In contrast, in much more affordable cities like Wigan, Liverpool, Blackburn, and Hull, zero homes were supplied through PDR.15

Relaxing the requirements for planning permission allowed new supply in PDR to be driven by local demand, which ensured new homes were concentrated in the cities where they were needed most. But because PDR conversions are limited to a narrow set of circumstances, supply remains decoupled from demand for every other kind of development. Aspects of PDR, including its use of office stock, the size and quality of the new homes permitted, have been controversial.15 These issues with PDR relate to the building regulations linked to this specific policy. Existing building regulations could be retained even as the planning system’s rationing of land use is reformed.

The combination of severe rationing of new supply with private home ownership and free-flowing capital is costly. State controls on private development means we have all of the volatility of capitalism without its productive potential. In cities with successful economies, due to controls on new supply, planning policy gives large increases in housing wealth to homeowners.

Policy supports homeowners, not home ownership

Another factor shaping housing wealth is the strong preference in the UK for home ownership over private renting, increasing demand for housing as an asset and therefore for housing wealth. Some reasons for this are perhaps cultural, but increasing home ownership is a widely-shared political objective. A number of government policies, therefore, privilege home ownership as a way to consume housing.

These include flagship policies such as Right to Buy and Help to Buy. Others that have received less attention include the stamp duty exemption for first time buyers; the exemption for capital gains tax on domiciled properties; and council tax valuations remaining at 1991 levels in England are all ways in which home ownership is subsidised by the state. These policies have been justified by successive governments partly because home ownership is seen as a pathway

to wealth.

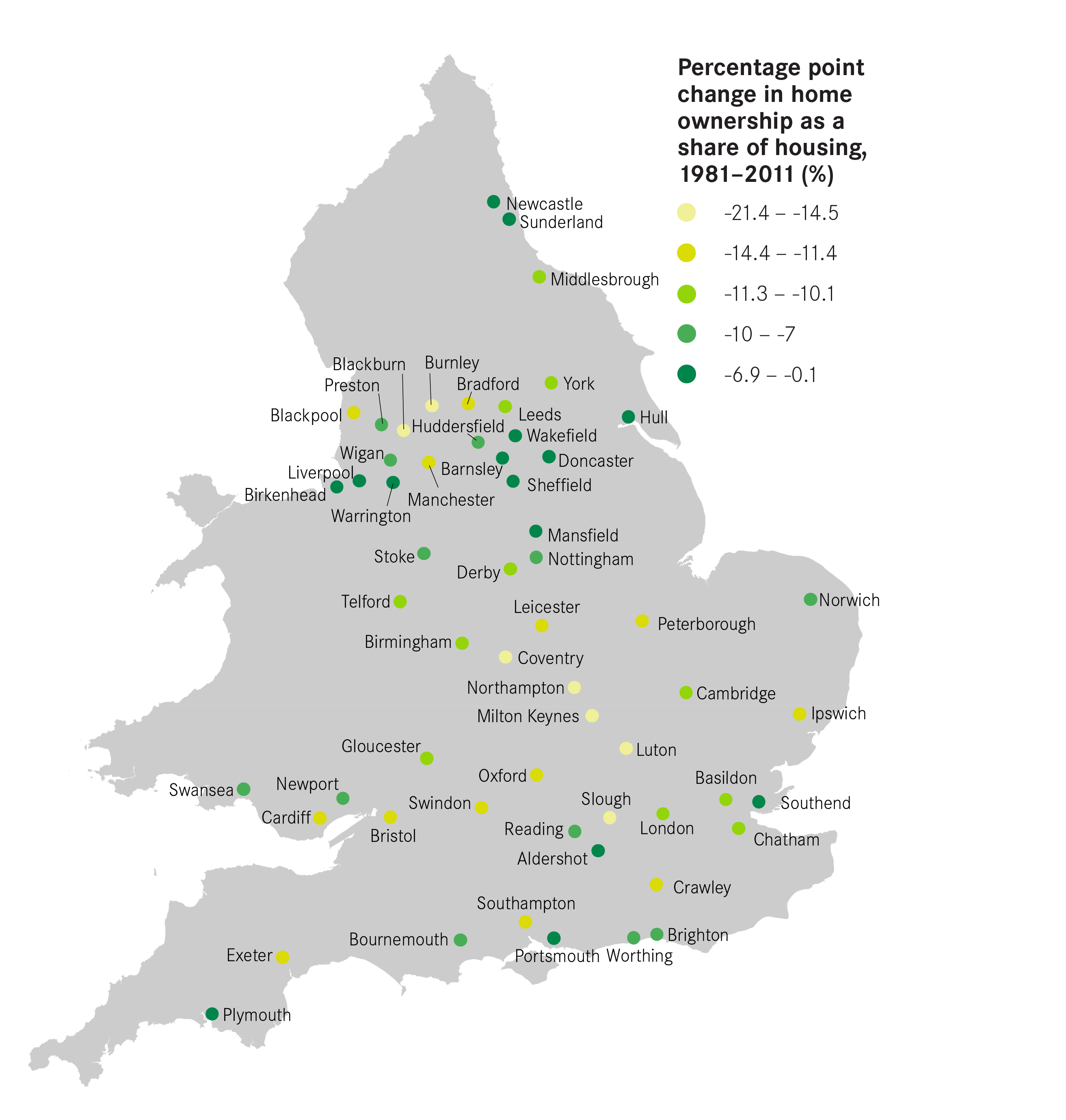

Not only does housing wealth accumulate in ways that sharpen inequality, these subsidies for homeowners have also failed to increase home ownership. Despite the introduction of these policies since the Thatcher government, home ownership as a share of private housing has fallen in every city in England and Wales since 1981, as Figure 10 shows. Similar patterns have also been observed in the US.17

Falling home ownership is not necessarily a bad thing. Households will always want varying amounts of flexibility and control when deciding whether to rent or buy but falling home ownership means Government policies to support home ownership are not achieving their objective.

These policies have struggled to increase home ownership because they do not address the primary barrier to housing affordability – a shortage of housing in cities with high wages. Rather than supporting home ownership, these policies mostly increase housing wealth by further inflating demand.

Policy should aim to treat private renting and home ownership neutrally. Policy support for private renters appears to be improving – the Government has abolished tenant fees and announced that Section 21 ‘no-fault’ evictions will be repealed. This should be matched with reform to the existing range of subsidies for homeowners to reduce inequality in housing wealth.

Homeowners use the planning system to block new homes and make inequality worse

An important feature of the planning system is the power it grants existing residents to influence housing supply through consultations into local plans and individual developments. Since the Skeffington Report in 1969, the planning system has increasingly tried to build support for new homes by providing more opportunities for public comment on services, infrastructure and design. These reforms, most recently in the Localism Act, have tried to build legitimacy for the planning system and reduce local opposition to new homes.

Unfortunately, these reforms have made wealth inequality worse by separating the supply of new homes from demand and contributing to housing shortages. By having consultations at every stage of the process, from the local plan through to the granting of individual permissions, the planning system gives existing homeowners the ability to protect their housing equity by campaigning against new homes.

When successful, these Nimby campaigns to reduce local housing supply increase the wealth of existing homes. Campaigners put pressure on local politicians and planners to build as little housing nearby as possible. By preventing new homes in areas of high demand, the value of their existing homes rises due to their scarcity. Local and national media then frequently report on these campaigns to reduce the supply of new homes without considering their impact on inequality.18

Sometimes the objections to new homes from Nimby campaigns stress issues such as congestion, public services, and the character of the local neighbourhood. But wealth inequality grows regardless of the stated aims of activists. While there may be issues with infrastructure and services that are associated with new supply, they are usually surmountable and can be resolved with good urban and transport planning.

The core problem is that although the planning system goes to great lengths to incorporate the views of existing residents, who generally want housing supply to fall, the interests of future residents and renters are under-represented in the planning process. British homeowners are more likely to oppose new homes in their neighbourhood, and evidence from the US suggests those who attend planning meetings are more likely to be homeowners and have unrepresentative , minority objections towards new supply.19 Importantly, this is not just a selection problem and would not be solved by “juries” of local residents.20

Rather, the issue is that allowing considerable and continuous input from existing residents disconnects housing supply from demand by ratcheting down the number of new homes that are built. For the planning system to represent the interests of people who do not currently reside in a community but who would if more homes were built, existing homeowners’ power to depress the supply of new homes at the local level must be reduced.

This would require a greater role for national government in representing the interests of future residents of places within the planning system. The input of current residents clearly has a place in the planning system but it should be in the creation of the initial plan, rather than with every single development that is proposed.

Higher rates of ‘affordable housing’ cannot address wealth inequality because their objective is not to slow growth in housing wealth

The political debate on housing and redistribution focuses frequently on how to redistribute new supply, whether through social- or cross-subsidised ‘affordable’ housing. The reality is that new supply is currently a very small amount of all homes. All of the housing added in cities from 2013 to 2018 amounts to just 4.4 per cent of 2018’s urban stock. It is not plausible to achieve significant reductions in wealth inequality across all of society by redistributing a fraction of a fraction of existing stock alone.

Furthermore, the objective of social housing and affordable housing is to make housing cheaper for the people who live in them, not to address housing wealth inequality as a whole. Both policy ideas would encounter problems if they tried to build sufficent numbers of new homes to address local housing shortages and cause growth in housing wealth to slow.

Cross-subsidy from private development for affordable housing requires private developers to make a profit for the subsidy to exist. If enough affordable housing was built such that development was no longer profitable, private developers would no longer build and create the subsidy. Similar issues face social housing, and it is not clear that the Government could build so much housing that the value of its own newly-built assets falls.

The priority for any agenda to mitigate wealth inequality should be ending local housing shortages. The central political choice of housing redistribution is not how to make a small fraction of new supply cheaper, but how to reduce controls on development in high-demand cities to make all housing cheaper.

Monetary policy choices are not responsible for housing wealth inequality, but housing shortages increase structural risk in finance

Cyclically cheaper credit has always increased demand for housing and increased house prices. The structural problem the UK and other countries with urban housing shortages face is that historically cheap finance has been unable to increase the supply of housing in cities where demand is high because of the rationing of land through the planning system.

This exacerbates housing bubbles in the short term.21 It also means that the ability of temporary investment bubbles in real estate to permanently increase the amount of housing and in the long run reduce house price growth in expensive cities is limited.22

This reinforces patterns of wealth inequality across the country and disrupts the financial system and the wider economy. For example, homeowners in expensive cities like London use borrowing to maximise their exposure to risk to try to capture as much of the equity gain from shortages as possible, regardless of when they buy in the real estate business cycle.23 Evidence also suggests that, during downturns in weaker local economies, inequality in housing equity reduces the positive impact of a reduction in interest rates by a central bank.24

Housing shortages in cities means policy has traded away cyclical risk in real estate for structural risk. Rather than having cyclical and local booms and busts in real estate, where risk falls upon developers and house buyers, the inability of cheaper credit to increase local supply when demand is high encourages aggressive approaches to risk by households and widens wealth divides across the country. In the event of a severe property downturn, highly-leveraged households lose out, but prices would not correct fully across cities because not enough housing will have been built in the cities with high wages and the greatest prices increases. This is exactly what was seen in London and other high demand cities after the house price crash of 2007 – as Figure 6 showed, house prices in the capital are way above their

pre-recession peak.

Financial regulation and monetary policy cannot be subordinate to housing policy, especially as financial conditions are increasingly determined by globalised financial flows. To be blunt, the US Federal Reserve is not going to effectively set global monetary policy to correct for the failures of UK housing policy. Instead, to reduce volatility and inequality, housing supply has to be responsive to these global conditions.

Crucially, this means that work to reform finance and reduce systemic risk will not be complete unless it considers how residential lending should link with economic geography. Reducing volatility in the financial system and reducing wealth inequality requires the planning system to be able to supply new housing in cities with high demand for housing.

In addition, it is possible that any solution to the housing shortage would require a change in macroeconomic policy to support a shift towards saving in other assets that do not give returns based on the performance of the local labour market.25

Some commentators and policymakers have suggested that monetary policy should be charged with controlling house price growth.26 But this is too blunt an instrument, as it uses policy designed to stabilise the national economy to try to change local outcomes. Today’s rises are much more shaped by local shortages across economic geography, and more or less expensive credit would not address the inequalities outlined in this report.