This report examines whether intra-urban public transport plays a role in the underperformance of big British cities and sets out the implications that transport has for the levelling up agenda.

Planning reform is needed to reconnect new housing to public transport infrastructure

What is the purpose of the planning system? Most people if you asked them, would probably say something along the lines of providing plentiful good homes and commercial spaces, protecting valuable nature sites, and joining up new development to infrastructure.

Yet despite the need for new housing with good transport access, and the poor public transport accessibility of British cities, existing public transport does not help provide as many new homes as it could. Since 2011, 47 per cent of all suburban neighbourhoods located near rail, tram, and tube stations have built less than one new house every year.

This is not due to a lack of stations or track, but rather how the current planning system rations out new homes in a highly politicised process far away from objections. Too often new homes are blocked in the locations with the best public transport. Instead, many are located on the outskirts of urban areas, forcing residents to depend on cars for urban mobility, even in cities with good public transport infrastructure.

Solving this depends on planning reform at both a national and a local level. If planning is to serve the public good instead of just blocking change, then it will need to change so that more urban land around stations is developed and can be used by the public.

Of course, different cities have different amounts of public transport. Cities with more stations will in theory find it easier to build homes near public transport, simply because they have more options. But if their share of new homes in walking distance of stations is lower than the share of existing stations, then they are dispersing new housing away from public transport rather than concentrating development near infrastructure that already exists.

Figure 1 plots this for each city from 2011-19, and it unsurprisingly shows that cities that have more public transport in walking distance of their neighbourhoods do build more homes near public transport – compare London to Oxford.

Source: Energy Performance Certificate Domestic Register 2020; TravelTime 2021. Suburban neighbourhoods (LSOAs) within a 10-minute walk of all railway stations (i.e. 50 per cent of the LSOA overlaps the 10-minute area) were identified using the same TravelTime data as in Centre for Cities’ Measuring Up report. Housing supply by neighbourhood identified using the same EPC data as the Sleepy Suburbs report. © OpenStreetMap contributors.

And on average, there does seem to be a gentle focus on putting homes in reach of public transport. In the average city, 15 per cent of all existing homes were in neighbourhoods near stations, and 17 per cent of all new homes were too. There were 31 cities above the dividing line, including Exeter, London, and Birmingham, which managed to concentrate a greater share of new homes in walking distance to stations than the existing stock.

But this was not the case everywhere. There are 27 cities below the line, such as Worthing, Bristol and Newcastle that have actually dispersed a smaller share of new housing close to public transport than the housing they already had in 2011. Adjusting for the amount of infrastructure they already had, it is becoming harder for their residents to use public transport.

This failure to connect new housing to stations is concerning when British urban areas have poor public transport accessibility compared to those in Western Europe of a similar size. For example, while 67 per cent of the residents of large Western European cities can reach their city centre in 30 minutes by public transport, only 40 per cent can do so in large British cities. This gap won’t close so long as large cities like Bristol, Newcastle, and Worthing are dispersing new homes far away from public transport.

Of course, different cities do have different amounts of public transport infrastructure, and this affects their ability to provide new homes near stations. Also, plenty of new homes not near stations will be connected to existing or new bus routes. However, neither of these reasons explains why cities struggle to concentrate new housing supply around the train, tram, and tube stations they do have.

The reason is large swathes of the suburbs in British cities are ‘dormant’ and make a minimal or no contribution to new housing supply, as development is blocked even in areas where it would be desirable. In contrast, the lion’s share of new homes are concentrated in certain ‘intensive’ locations, usually in city centres or in car-dependent estates on the outskirts of cities.

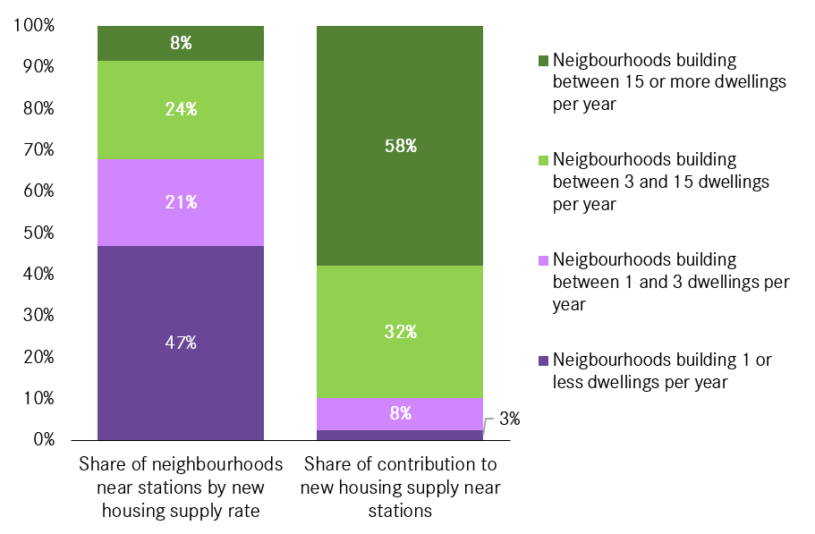

Yet, even though the planning system locates new homes in certain locations, it does not actually manage to concentrate them near public transport stations. Figure 2 shows that development of land near stations is lopsided – 8 per cent of neighbourhoods near stations are ‘intensive’ and build 15 or more homes a year, contributing 58 per cent of the total increase in housing supply near stations. However, 47 per cent of neighbourhoods near stations are ‘dormant’ and add less than 1 new house every year (dark purple). These neighbourhoods contributed just 3 per cent of the total increase in housing supply near stations.

Source: Energy Performance Certificate Domestic Register 2020; TravelTime 2021. The ‘intensive’ threshold has been decreased from 25 or more homes per year in Centre for Cities’ earlier report Sleepy Suburbs to 15 per year in this blog post as many cities have very few or zero neighbourhoods near stations that are building at that higher rate. © OpenStreetMap contributors

In other words, almost half of all suburban neighbourhoods near existing railway, tram, and tube stations make a minimal or no contribution to new housing supply.

This trend was observed across all cities in England and Wales. Even cities that build a large proportion of new housing near stations only build on a small proportion of the land near stations. For example, in London, where 70 per cent of new houses are within a 10-minute walk of a station, 42 per cent of the actual neighbourhoods near stations are ‘dormant’, adding one new home or less per year.

The reliance on intensive neighbourhoods, where lots of new homes are concentrated in specific neighbourhoods to meet housing targets, has an additional consequence. Large numbers of homes in some cities are being built nowhere near stations. In cities like Milton Keynes, Swindon, Peterborough, and Telford, which are all in the top ten cities for housing supply growth since 2011, less than 10 per cent of all new homes are near stations.

This is not necessarily their fault – it would be hard for Peterborough to do much more when it only has one active railway station, for instance. But Milton Keynes has six railways stations, and is building 95 per cent of its homes out of walking distance of any of them. As recent research from RTPI and Transport for New Homes also shows, England’s planning system is at the national level often concentrating the country’s new housing on the outskirts of cities and forcing their residents to depend on cars for urban mobility.

In principle, the planning system should ensure that urban land and infrastructure is used more effectively over time. For this to happen, new housing should be concentrated near public transport stations, and urban land near stations should be denser than land further way.

However, this does not happen in British cities. The planning system’s poor performance is not the fault of individual planners, councillors, or local authorities, but it is an inevitable outcome of the English planning system’s internationally unusual degree of case-by-case decision-making. This does not just ration and reduce the amount of new housing that is built, but it also politicises the planning process and concentrates development in tolerable rather than sensible locations.

A more ‘rules-based’ flexible zoning system – where builders can instead build if they follow the rules – would not only increase the overall supply of new homes. By depoliticising individual planning decisions, local supply would be reconnected to local demand, including within cities. Planning would instead concentrate new homes on the most valuable urban land, such as that near public transport stations, rather than on the outskirts of the city far away from objectors.

Building more homes near stations and improving public transport accessibility therefore requires planning reform. At the national level, Government should continue the planning reform process and shift away from the current ‘discretionary’ system towards a rules-based flexible zoning system.

Ahead of any national reforms though, local authorities should allocate land around train stations for development in their local plan process. Some cities like Bristol are attempting to change, and have recently adopted supplementary planning policy documents to achieve this. But even cities like London that have been doing so for over a decade have room to be more ambitious. Land around stations in the green belt should also be released for new homes, due to their excellent transport infrastructure.

Around stations in built-up areas, local authorities should also consider using Local Development Orders (LDOs) rather than a standard site allocation to introduce a more rules-based planning approach.

The types of buildings near stations will change if we do this. There will be a gradual shift away from low-rise, terraced and semi-detached dwellings. Most stations will have more mid-rise buildings of four-six storeys in walking distance, with a few of the busiest stations seeing some even a bit higher.

At present, the planning system too often fails to connect new homes to public transport. Fixing this depends on building a new urban form and a new process of planning. But in return, we would have better planned cities, and planning that would serve the public good. Less congested, more affordable, and more environmentally friendly cities are in reach – we only have to decide we want them.

This report examines whether intra-urban public transport plays a role in the underperformance of big British cities and sets out the implications that transport has for the levelling up agenda.

This report uses new data to examine which neighbourhoods within cities are building the most and the least new homes and explores what this means for policy making.

Ten case studies comparing the public transport networks and urban form of UK and Western European cities

Major cities across the North are lagging behind their European counterparts in providing access to quality public transport networks, costing the Northern economy more than £16bn in lost productivity.

Leave a comment

Jonathan Hall

The Energy Performance Certificate Domestic Register 2020 is a useful data source for identifying new builds, thank you for bringing this to my attention. However I’ve noticed through an analysis of the Register on local data, concerning a local area I know, conversions of existing buildings (eg redundant office buildings) into flats/apartments etc have been classified as ‘new dwellings’. I would have thought these type of conversions would be in urban areas/city centres etc, rather that new greenfield sites in the suburbs/edge of towns etc. Which might affect the results of the study?