In response to a consultation last year, the Government has proposed a change of the rules that cover the formation of combined authorities (CAs), including a relaxation of certain requirements. Previously prohibited, councils will now be able to form CAs with other councils that are not direct geographic neighbours, or to form doughnut shaped CAs around authorities who do not wish to join.

But while change is needed in the way councils can come together to form CAs, these new flexibilities will do nothing to resolve the main issues that councils face in doing so.

Combined authorities provide joined-up strategic leadership across councils at the scale of the real economy. They provide a practical and pragmatic solution for enabling authorities to work together to deliver on the transport, infrastructure, housing and skills policy that are crucial for local people, jobs and businesses. For this reason, it is difficult to see how combined authorities that allow satellite councils, or ‘doughnut holes’ could effectively deliver these services and strategic leadership. Picture Greater Manchester combined authority attempting to design and deliver transport policy without Manchester City Council as a full and willing member at its centre, for example. Or consider the difficulties in formal statutory housing policies relating to Leeds City Region, as well as the city of York but not the districts of Selby and Harrogate (part of North Yorkshire County Council), being part of the arrangement as well.

(Map source: wikipedia)

(Map source: wikipedia)

The more pressing issue is that many authorities within a functional economic area cannot join together to form a combined authority because of rules on the eligibility of authorities in the two-tier system of local government – the Government has not proposed to change these.

Many cities would benefit from forming combined authorities with councils with whom they share strong economic links, including district councils that cannot join without the entire county of which they form part of joining as well. In most cases the real economic geography of an area does not match the administrative boundaries in place, and this is especially prevalent in, though not excluded to, small and medium sized cities.

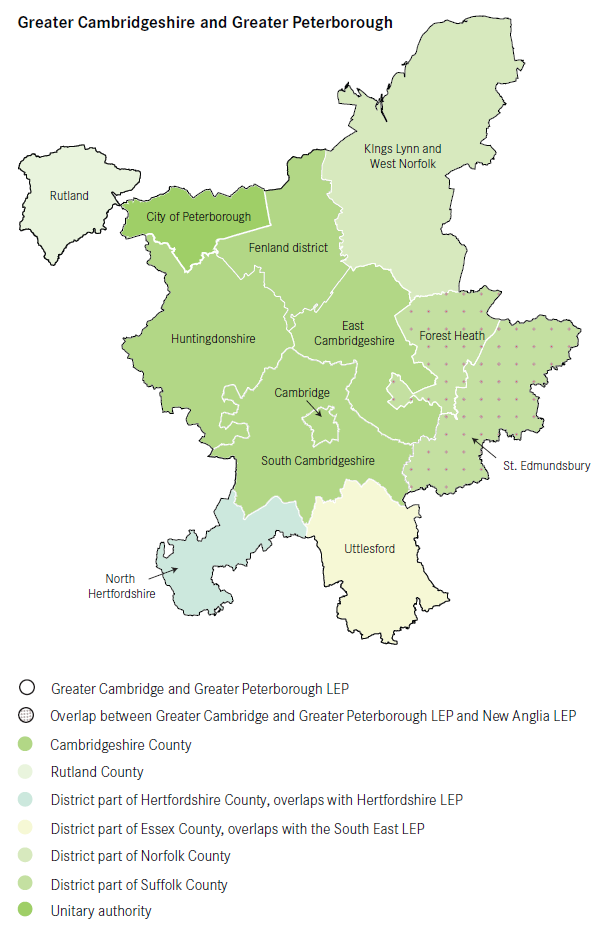

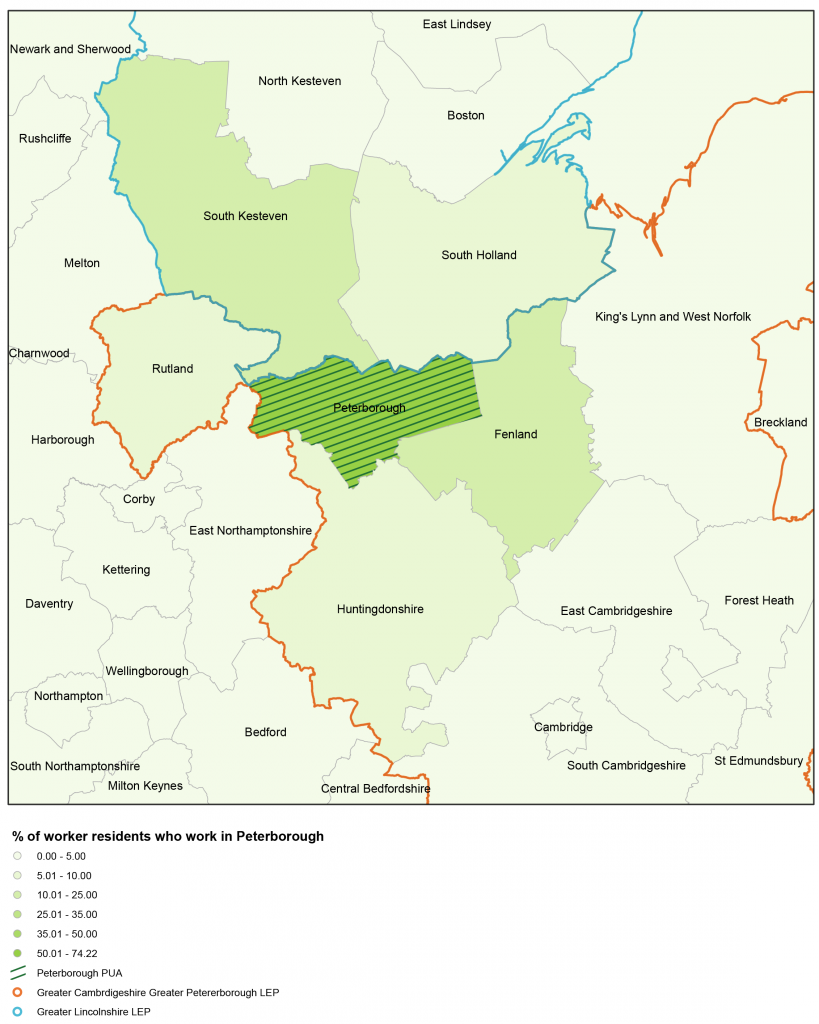

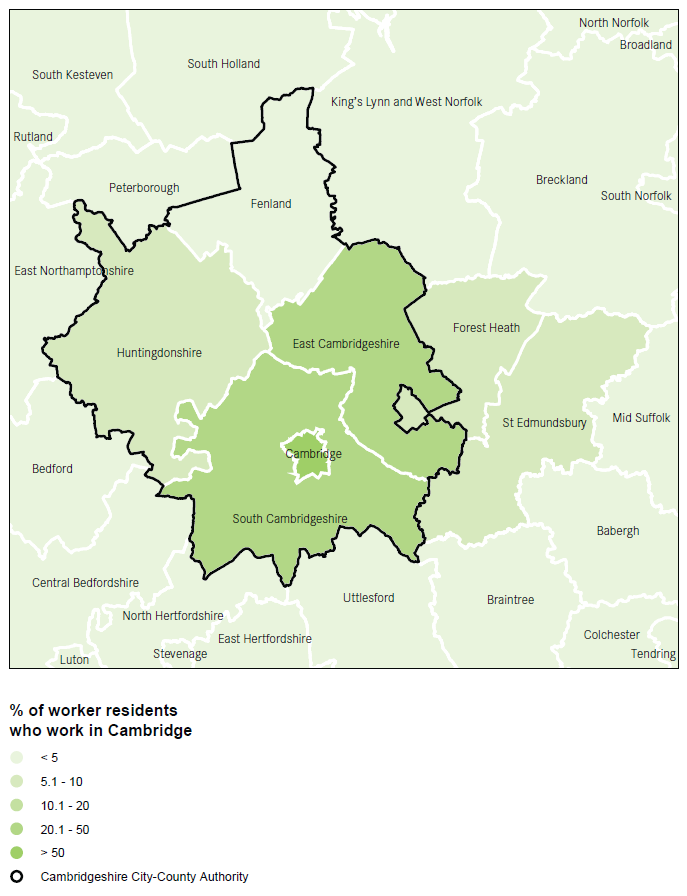

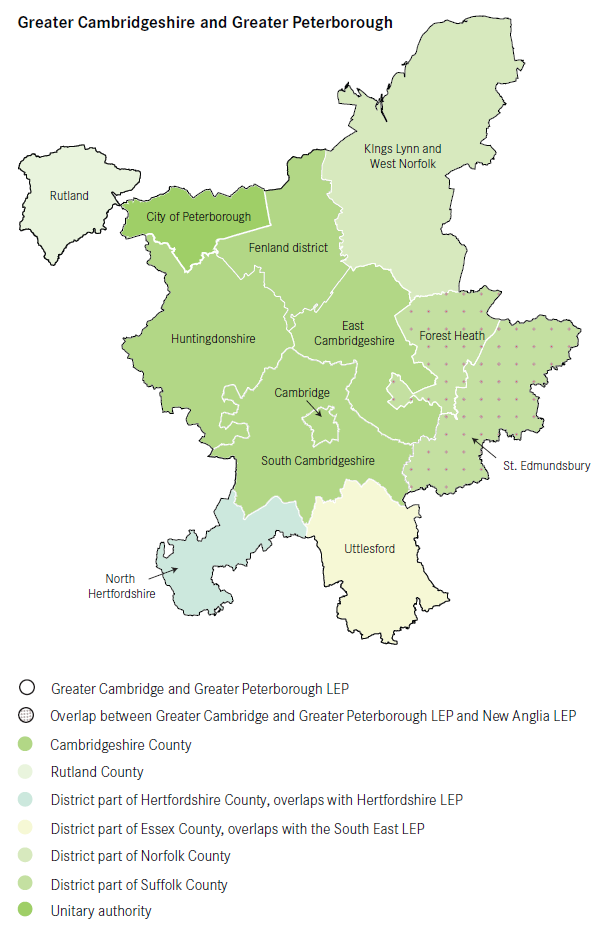

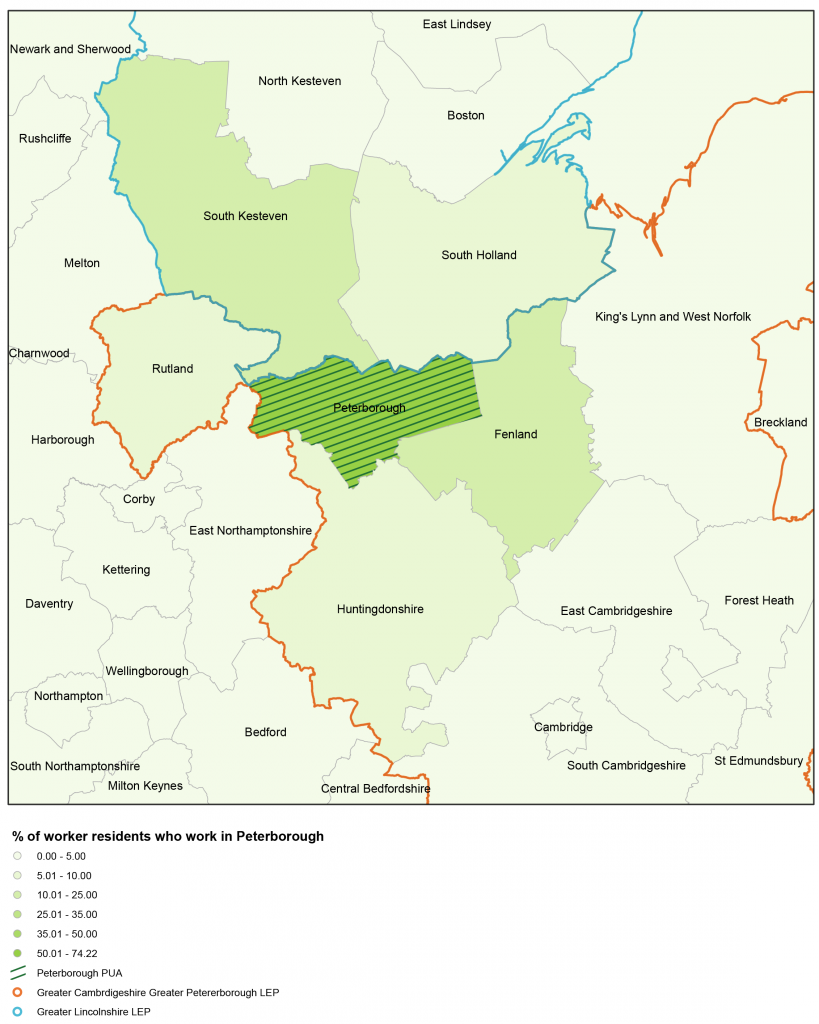

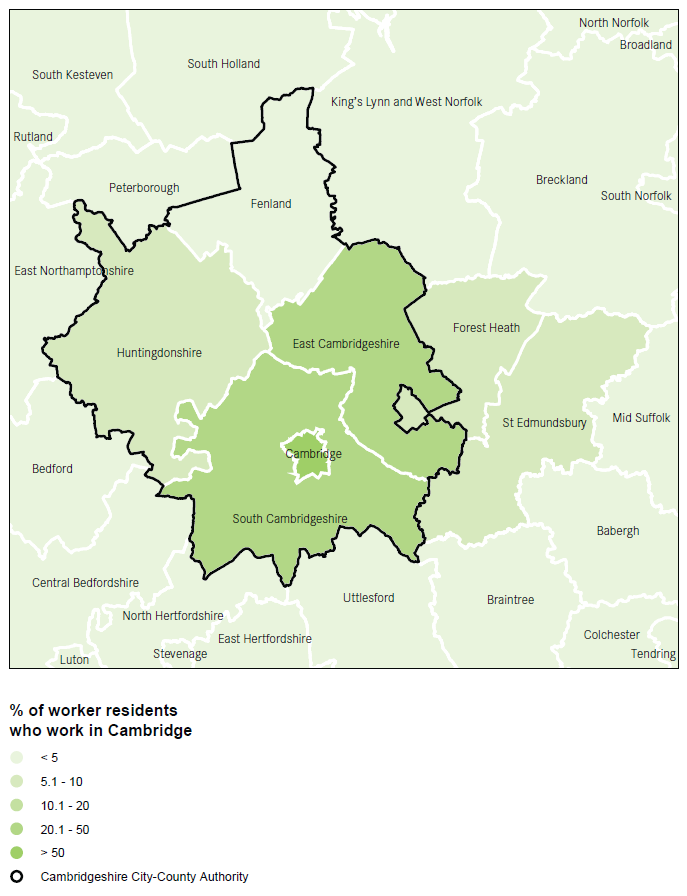

The map above shows the cities of Cambridge and Peterborough, and the districts and counties that surround them. The maps below illustrate commuting patterns into the cities of Cambridge and Peterborough. Peterborough visibly has strong economic ties with Fenland and Huntingdonshire districts of Cambridgeshire County Council (as well as in Lincolnshire and Rutland), while Cambridge has especially strong ties with South and East Cambridgeshire district councils. The change in the rules will do little to help Cambridge or Peterborough support economic growth through combined authorities at the scale at which their economies operate.

Similar issues come up in Brighton, where commuting patterns show strong ties between the unitary Brighton authority and neighbouring authorities, including with district councils in both West and East Sussex. Here again, the proposed changes do not improve the ability for district councils with strong economic ties to other metropolitan, unitary or county authorities to work together on strategic transport, housing and skills issues that matter most to the economy.

Evidently, the administrative make-up of England and the economic geographies of cities across the country are very complex, and there is no single or simple solution. But supporting areas that share strong economic ties to work together on the strategic planning, housing and transport issues that matter so much to unlocking economic growth is vital, regardless of their designation under the current complicated two-tier system of government. And looking ahead, if more combined authorities are successfully created, this raises questions about the future of the current configuration of local government, particularly the two-tier element, and whether it is fit for the task of supporting economic growth.

Leave a comment

Derek Whyte

It is true that one of the challenges for councils on economic issues is always to distinguish their interests as institutions from the economic interests of the wider functional economic area to which they belong. That is why discussions about coordination on economic affairs turn rapidly to discussions about governance.

Some of this can be blinkered navel gazing of very little interest to businesses and residents of the area, outside the local government bubble. But some of it has deeper resonance. Combined Authorities are in essence a governance mechanism which allows for the pooling of sovereignty by individual councils for the greater good – and the proposed legislative changes are designed to ensure that a small number of refuseniks cannot upset the apple cart where a majority of authorities are keen to co-operate using that mechanism.

You point to some of the obvious problems which could arise under this approach. The obvious alternative would be to have a mechanism which ensured that a (say two thirds) majority of councils within any proposed CA area would be binding on the minority. This is in effect how the issue of precepts was decided within London, in respect of London-wide bodies, following the abolition of the GLC. Then, a budget was set for each London-wide body by majority vote of the 33 London Boroughs and the City of London. Assuming that passed the two thirds majority then it became binding on all the others to pay (pro rata to population).

Over the course of these arrangements a minority of boroughs did propose moving to a smorgasbord arrangement – with each only paying for whatever services it wished to purchase – but this was not considered operationally realistic by the majority of councils, irrespective of political control.

Of course, there are two main differences there – the area of Greater London was clearly defined from the outset (unlike CA areas which are to be self defined); and the scope of the compulsion was limited to precepting in a limited number of areas . Outside of those circumstances, it becomes more difficult to propose use of that model in the face of democratic opposition by one or more councils. Probably best then to leave the issue to elightened self interest and the verdict of the voters if attitudes struck by one or more councils are felt to be perverse.

The other relevant point is that the changes proposed by government also open to door to councils in an area adjacent to a CA, but not contiguous to them, to ask to join the CA. One could envisage circumstances where, if there was a lack of agreement between councils, or tiers, within one area, for a council or councils in that area, to ask to join up with a neighbouring CA which might better serve their interests, even where functional economic linkages might be weak. It may be interesting to see how/whether/where that may happen.