Centre for Cities’ new report, Cities Outlook 1901, explores how cities are shaped by their past. It shows how cities and why cities have taken different paths over the course of the 20th century. The story of Birmingham provides some interesting lessons for current and future policy.

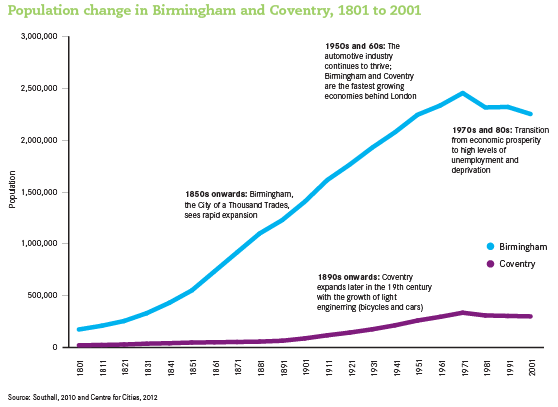

If you lived in Birmingham back in 1901, the chances are life would have been pretty good. It was the fourth largest city in the country at the time (behind London, Manchester and Liverpool) and a magnet for people looking for economic opportunity. The ‘City of a Thousand Trades’ was a workshop full of small, highly skilled firms producing a huge range of products. As a result, levels of enterprise were high and unemployment was low. At this point 12 percent of employment in the city was in vehicle manufacture.

Then came the 1930s. The cheap Pound, availability of credit and rearmament led to the rapid expansion of manufacturing in the city – predominantly in the automotive industry. With organisational and technological change also came the expansion of unskilled and semi-skilled labour in the city.

While the city saw huge numbers of new jobs created over the first half of the 20th century (unlike other manufacturing centres), it also become increasingly specialised in the automotive industry. The high cost of wages and rent in the city, coupled with the impacts of the 1945 Distribution of Industry Act to redistribute jobs, made it increasingly difficult for new industry to locate in the city. By 1951, 72% of the manufacturing workforce were employed in the automotive industry.

The 1970s recession forced the collapse of the automotive industry. As a result, Birmingham, which had followed a very different path from other manufacturing centres in the decades following 1901, saw a striking transition from high employment and high wages to high unemployment and deprivation. The city has since seen modest jobs growth, driven primarily by the public sector.

The story of Birmingham is not a critique of the automotive sector. The West Midlands today is still home to valuable jobs and innovation in the industry. What is does tell us, however, is that over reliance on a single industry makes a city economy more vulnerable to changes in the wider global economy. It also highlights the potential adverse effects of policy.

Cities should constantly be considering how they can make the most of niche strengths but also how they can encourage greater industrial diversity. For many cities the focus will need to be on the fundamental drivers of growth: skills and infrastructure. Cities need to work with local providers to ensure education and training responds to the needs of the modern economy and target investment in infrastructure to ensure cities are both better connected and attractive to workers and businesses.

Leave a comment

Be the first to add a comment.