The Government has today launched StartUp Loans, a scheme designed to encourage young people to start up their own business. But while the scheme targets an important issue, lessons from previous policies suggest that in its current format it is likely to have limited success.

The scheme will make loans of an average size of £2,500 to people aged between 18 and 24 and will run for three years. There will be a selection process, so that not all people that apply will be approved for the loan. But every applicant will get access to mentoring, including those that aren’t successful.

Any ideas on how to boost enterprise rates should be encouraged – our forthcoming work on enterprise across UK cities will show that the entrepreneur has a very important role to play in city economies. But there are two problems with the StartUp Loan approach.

Firstly, earlier work by the Centre has shown that previous enterprise initiatives have had a poor success rate. There have been a raft of enterprise policies, ranging from the 1980’s Enterprise Allowance Scheme, which encouraged the unemployed to start their own businesses, to a multitude of enterprise policies aimed at deprived areas under New Labour. But, despite this, business start-up rates have remained stubbornly stable across cities.

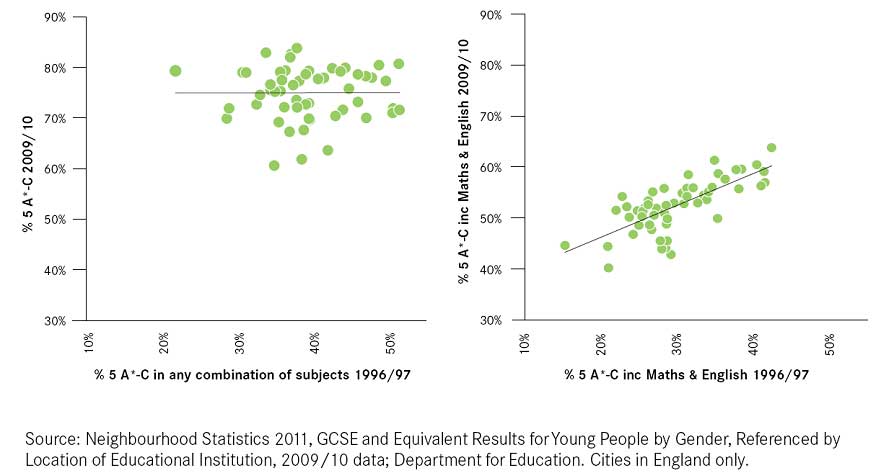

Secondly, this approach does little to address the problem that skills plays in youth unemployment. Our recent report Learning Curve showed that cities that had more young people with Maths and English GCSEs are much less likely to have high rates of youth unemployement (although interestingly general GCSE attainment has little bearing on youth unemployment, see below). The question is, if lack of numeracy and literacy skills is a key driver of youth unemployment, is encouraging enterprise the right policy fix to tackle worklessness amongst 16 to 24 year olds?

If access to capital is a problem for businesses then it is useful for government to step in. And the mentoring scheme, which appears to be in part inspired by Dragon’s Den, could offer a more tailored approach than Business Link provided in the past.

But if access to cash and lack of experience are real problems, they are likely to affect more than just young people. For example, older entrepreneurs are often falling over themselves to secure the mentoring services of the Dragons on the BBC2 show, despite the large equity stakes they give away for it. For this reason the scheme would benefit from applying to a much wider age range – although it could continue to focus the offer of mentoring to unsuccessful bids on young people rather than the wider population.

In general, however, young people usually benefit from some experience of the working world before venturing on their own enterprise. The majority of people in the UK tend to be in their thirties when they set up a business (see Figure 9 of this BIS report). This is likely to be more about the experience that older people have gained rather than any bias against young entrepreneurs. Planting the seed of enterprise in young people’s minds is unlikely to flourish tomorrow. But it could shape longer term ambitions. So instead of StartUp Loans, how about a scheme that allows a much larger group of young people to shadow local entrepreneurs instead? Encouraging young people who may not have thought of entrepreneurship before, and equipping them with the information about how to set up and run a business, could reap dividends in the longer term for UK plc.

Leave a comment

Be the first to add a comment.