Meaningful economic rebalancing will be impossible if the Government doesn't match its ambitious homebuilding targets with an ambitious new planning system.

Stamp duty holidays may be justified whilst the pandemic continues, but they are not a longterm option. What does the future hold for the holiday and local taxation for cities in the post-Covid world?

Last July the Chancellor brought in a stamp duty holiday for up to the first £500,000 of any sale in an attempt to get the housing market moving. As March’s budget approaches, the Covid crisis continues and calls are being made to extend the holiday.

How has this holiday played out across the country? And what is the future of stamp duty and local taxation for cities?

Home sales have recovered somewhat from their April 2020 low, and this has happened across England as Figure 1 shows. While it’s impossible to say at this stage what contribution the stamp duty holiday has made, it is plausible that it was responsible for some of the increase.

Figure 1: Housing sales by month across England, 2020 (February = 100)

Source: Land Registry Price Paid data, 2021

But in monetary terms, this policy has very much benefited homeowners in the Greater South East.

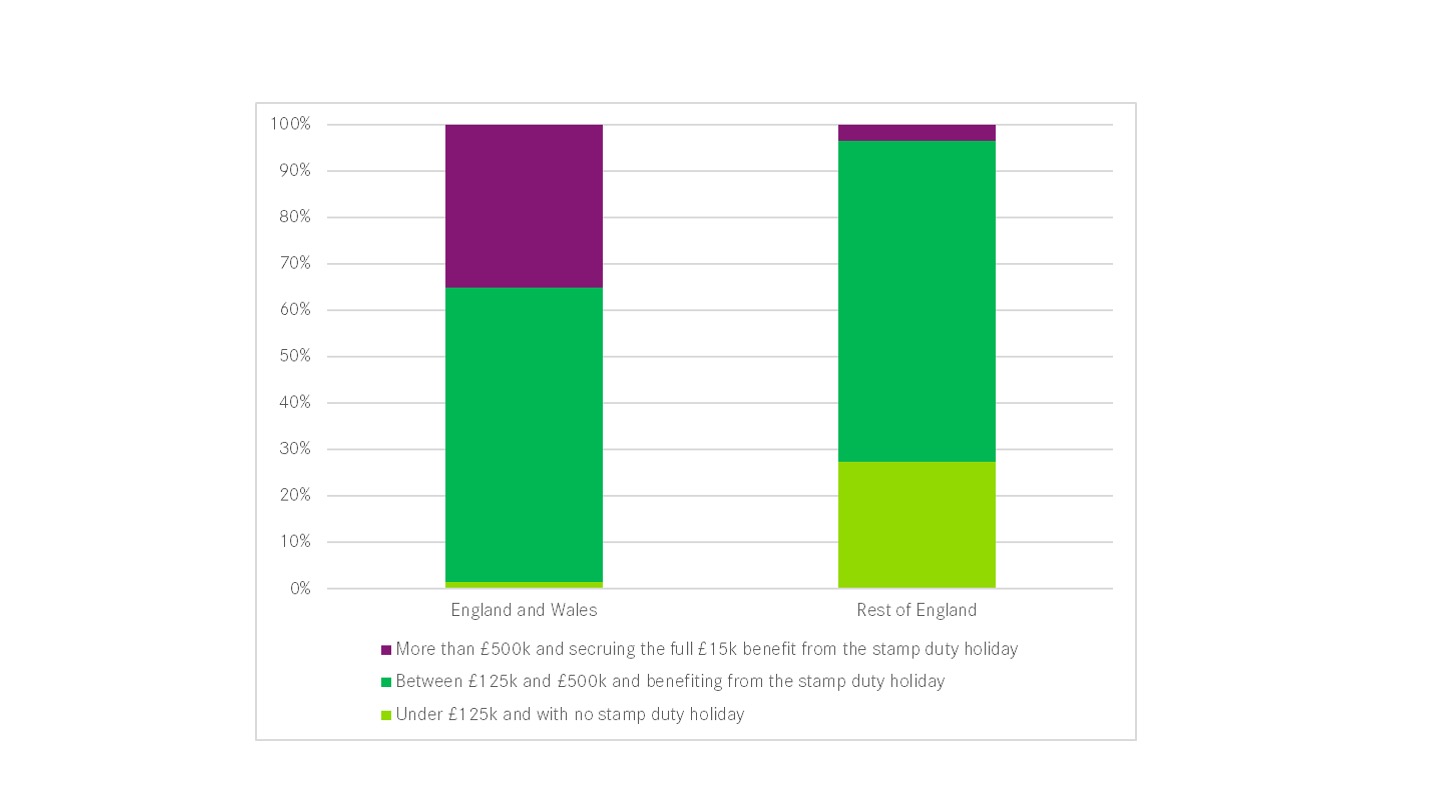

Houses in England can be grouped into three types by the current stamp duty holiday. Those which sell for between £125,000 and £500,000 have had stamp duty reduced to zero. Houses which sell for £500,000 or more have continued to pay stamp duty, but enjoy the maximum stamp duty reduction of £15,000. Houses which sell for less than £125,000 have continued to pay no stamp duty.

The majority of houses sold in cities in England since July last year fall into the first group – 67 per cent were between £125,000 and £500,000 and so received some benefit from the holiday. 17 per cent were cheaper than £125,000 and saw no benefit from the holiday, and 16 per cent of all those sold were above £500,000 and so captured the full £15,000 discount.

But this national picture hides the geography of the stamp duty holiday. While again roughly two thirds were in that first group in cities in both the Greater South East (the South East, London, and East of England) and the rest of England, this was not true for the other two groups.

35 per cent of homes sold in the urban Greater South East since July were worth more than £500,000 and enjoyed the full holiday, and only 2 per cent saw no discount. This relationship was though reversed in cities elsewhere in England, as Figure 2 shows. 27 per cent of homes sold in cities in the rest of England from July onwards saw no benefit from the stamp duty holiday, and only 4 per cent saw the maximum £15,000 discount.

Figure 2: Homes sold since July in English cities

Source: Land Registry Price Paid data, 2021

This becomes particularly striking in certain individual cities. While 38 per cent of homes (127) sold in Oxford after July captured the full-fat £15,000 holiday for homes above £500,000, only one was sold below the £125,000 threshold. In Hull, 57 per cent (472) of housing transactions saw no benefit (because they were below the £125,000 threshold), and only one fortunate homeowner in Hull enjoyed the complete £15,000 holiday.

This can be seen when looking at average sale prices too. The map in Figure 3 shows that there is a clear geography to where the discounts were granted across the country. While the average sale in London, Cambridge, and Oxford got the maximum £15,000 benefit, as average prices were above £500,000, the average sale in Burnley and Hull realised no benefit stamp duty due to being below £125,000. In Sunderland, the average sale received a benefit of £21.

Figure 3: Average stamp duty discount across cities in England, 2020

Source: Land Registry Price Paid data, 2021

This means that homebuyers in the Greater South East as a whole (including urban and non-urban areas) saved £1.48 billion in tax – 66 per cent of the total cost of the policy to date.

This opens up thorny questions for stamp duty in the short and long term, as although the Chancellor is thinking about extending the holiday, some voices such as the Daily Telegraph are calling for it to be scrapped.

The holiday is currently due to expire on the 31st of March, which is imminent given how long it takes to complete house purchases. If the third lockdown continues to or beyond that date, it is possible that the housing market will see transactions fall again. The Government may therefore decide to extend the stamp duty holiday if it wishes to avoid this outcome. But it will mean a continued skewing of relief to the Greater South East.

The longer term problem is trickier. Although stamp duty is an inefficient tax that discourages people from living where they want, it is progressive. Abolishing stamp duty outright would therefore not only open up an annual £12 billion hole in Government finances, but it would also give disproportionate benefits to better-off homeowners in already prosperous parts of the country.

Continuing with business-as-usual with stamp duty once the pandemic is over is of course one option for the Government. But for policymakers keen on major reform, there are other possibilities. One option would be to replace stamp duty with a capital gains tax on homeowners’ dwellings. This would also be progressive, be much more efficient than stamp duty, and give a permanent tax break to homeowners in cities with low capital gain, mostly outside the Greater South East.

The other option is to use stamp duty reform as a lever to fix another tax problem – the regressive design of council tax and the local government funding crisis. Abolishing stamp duty and shifting towards a new annual property tax, with valuations updated every year, would be a path towards greater fiscal devolution and more self-reliant and responsible local government in England, alongside fairer taxation.

Regardless, while stamp duty holidays may be justified so long as the pandemic continues, endless holidays are not an option. Stamp duty’s problems can only be solved by its replacement – whatever that may be.

Meaningful economic rebalancing will be impossible if the Government doesn't match its ambitious homebuilding targets with an ambitious new planning system.

Ivan Tennant on how building new homes in the suburbs can help solve the housing crisis.

This report uses new data to examine which neighbourhoods within cities are building the most and the least new homes and explores what this means for policy making.

Ending the planning system’s rationing of homes is essential to end England’s systemic shortage of housing.

Leave a comment

Be the first to add a comment.