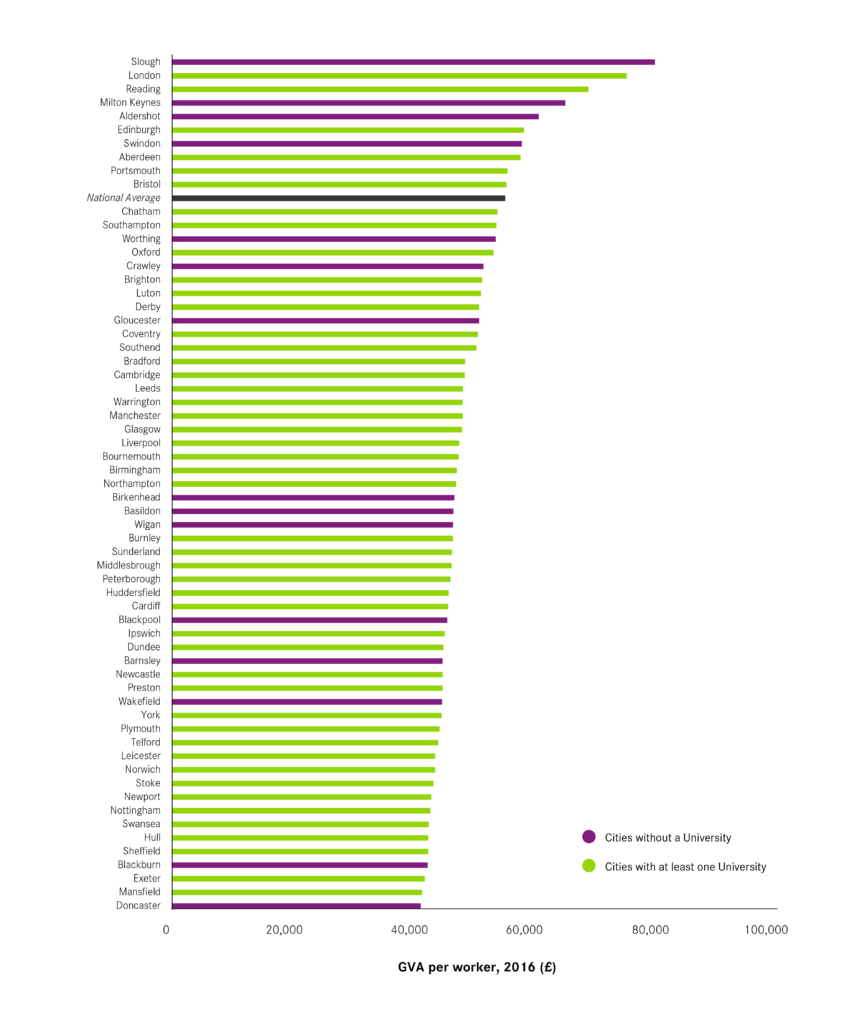

Similarly, there are weak economies both with and without universities. Doncaster and Blackburn might claim a reason for their low productivity per worker is a lack of universities in their cities, but the truth is that Hull, Sheffield and Swansea do have universities, and are among the least productive city economies.

While one might argue that having a university would make Milton Keynes even more successful (and they are indeed planning to open a university) and that not having a university would make the situation worse for Hull and Sheffield, looking at the reasons put forward as to why a university would have a positive impact on the economy does not provide a compelling case for the argument.

One popular line of thought is that having a university increases the number of graduates available in an economy. But, despite Crawley and Slough not having a university, both cities have no problem in attracting in fresh graduates. Meanwhile, cities such as Sunderland and Bradford really struggle to retain recent graduates from their local universities. And as discussed in our recent graduate retention blog, this is mainly the result of the availability of long-term job opportunities in a local area.

Another argument is that universities can support economic growth by working with existing local businesses and attracting new ones. Our previous research shows that while this is true, the impact is very small. Spin-outs from universities do tend to have higher turnovers than the general business base, but they make up a tiny proportion of the business base of cities: for example, between 2004/05 and 2007/08 they accounted for just 0.1 per cent of all business start-ups in Manchester. In Oxford – the city with the highest number of spin-outs relative to all business start-ups – the figure was just 1.3 per cent.

While universities do undoubtedly bring benefits to the local economy in which they are based – particularly in terms of student spend – in the grand scheme of things they do not by themselves have the power to turn a city with a declining economy into a thriving place. Instead, what is needed is a concerted effort on multiple fronts to make cities a better place for businesses to locate and for individuals to live. In terms of skills specifically, cities without a university should focus on improving the skills of those that have very few or no qualifications, especially in Maths and English, before chasing a new university campus.

Leave a comment

Be the first to add a comment.