Bottom of the class: which cities have no high-quality secondary schools?

Access to quality education is hugely uneven across the country. Tackling this problem should be a top priority for leaders.

Access to quality education is hugely uneven across the country. Tackling this problem should be a top priority for leaders.

The Government has today announced £70 million investment for initiatives aimed at improving education in disadvantaged areas, and unveiled further plans for its ‘Opportunity Areas’ initiative, which is aimed at increasing social mobility through education.

This intervention is timely, for as a recent study by the Education Policy Institute (EPI) shows, access to quality education varies hugely across the country – and these disparities are getting bigger. If you happen to live in Slough or Reading, the chances are you will be able to send your kids to a high-performing secondary school. But if you live in Barnsley or Middlesbrough the odds are not in your favour.

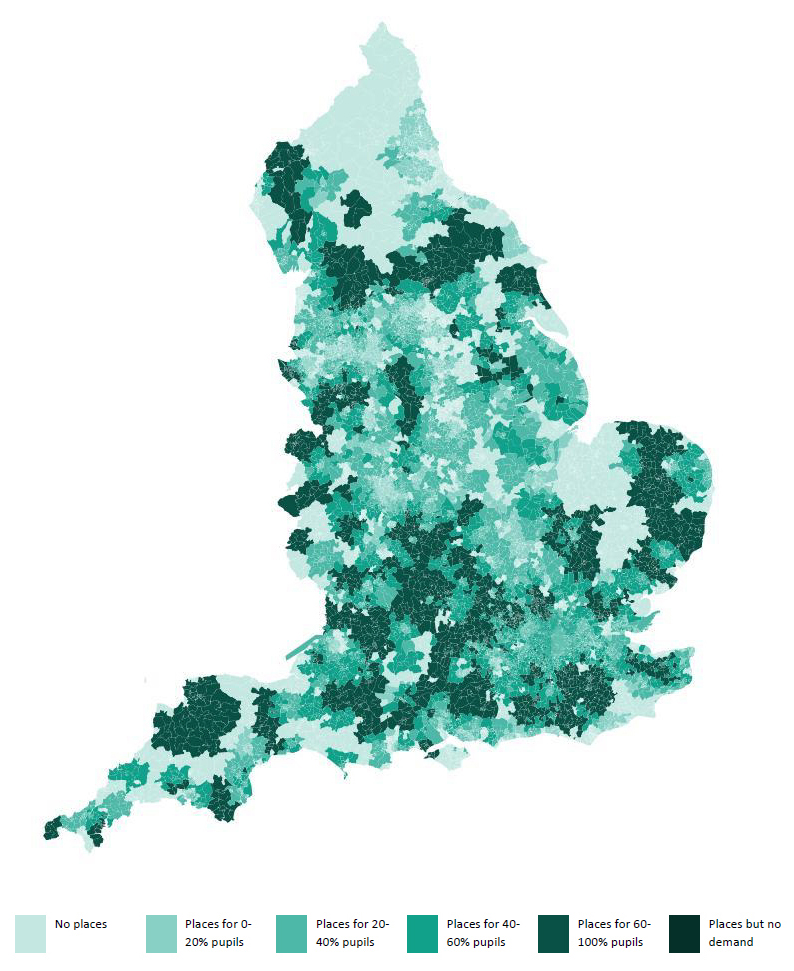

The EPI study shows that not only is access to high performing schools unevenly spread out across England, it has also become more geographically unequal over time. As the map below illustrates, cities mostly concentrated in the south have a better offer of high quality secondary schools than places further north, with some parts of the country – such as Barnsley, Middlesbrough, Blackpool and Wakefield, just to name a few – having barely any high-performing secondary schools. Furthermore, while in most southern cities access has improved over time, places further north – and in particular in the North East – have seen a decline in the quality of secondary education, meaning the gap is widening across the country.

It is striking to see how those very same cities with almost no high performing schools also have weaker economies. Productivity in places like Barnsley and Middlesbrough is 1.5 times lower than that in Slough and Reading, and this is similarly true for workplace earnings. For every Knowledge Intensive Business Services (KIBS) job in Barnsley, there are three KIBS jobs in Reading. And Reading has more than twice as many people with high-level qualifications than Barnsley.

Combining these figures with findings from EPI paints a bleak picture. Not only are pupils in Barnsley and Middlesbrough leaving school less prepared for the world of work, but they are also entering a weaker labour market with much less opportunities than in cities such as Reading and Slough. In turn, these weaker labour markets – supplied with an under-performing workforce – will struggle to attract higher-skilled business investment.

These two factors create a vicious cycle which undoubtedly condemns already weaker places to an even gloomier future, and contrast with the brighter opportunities for places and people living further south where the economy is stronger and the quality of education is higher.

The Government’s main initiative to address these issues has been the Opportunity Areas programme, which it launched in 2016, and which it announced further plans for today. The initiative is focusing local and national resources on increasing social mobility through education in 12 opportunity areas. These areas – which include Blackpool, Bradford and Derby – were selected from a list of 32 areas identified as poorly performing in terms of social mobility and school performance and are now in the process of setting up their action plans to tackle the issue.

It is hard to anticipate the outcome of this initiative, but it is welcome to see that one of the Government’s key objectives for the project is to collect evidence and identify ‘what works’. The Government has commissioned the Education Endowment Foundation (EEF) to evaluate the impact of opportunities areas by designating an EEF Research School in each area. This will provide insights on the lessons learnt from the initiative, which will then be applicable more widely to schools and other education institutes across the country.

The Government’s commitment to prioritise certain areas and evaluate the impact of a policy is commendable, and isn’t done frequently enough across other policy areas. But it does also mean that cities such as Barnsley and Middlesbrough – which are not included in the scheme, but where educational outcomes need to be addressed – will continue to offer poor access to good schools without any policy intervention. This is bad news for both those cities and the pupils living in them.

In the absence of more tailored support, places should nevertheless start acting now to find solutions to one of their biggest economic problems. The Government’s recent ‘Unlocking talent, fulfilling potential’ strategy (published in December last year) offers two ways forward: through forming stronger relationships between schools and businesses and other community groups, and better evaluation of policy. In addition, the cities should identify the root causes behind their poor secondary-school performance – for example, whether they are related to poor teaching quality, or low aspirations. They should then design interventions aimed at tackling these issues. Two examples of this would be paying a premium for teachers, as Stoke has done, or by better engaging students with the subjects they are studying, as done by the West London Zone.

Improving school performance is a crucial part of making an economy more attractive to business investment, and yet it is almost always overshadowed by more marginal interventions, such as graduate attraction and retention policies or capital of culture bids. This means that it needs to be a top priority for both national policy-makers and local leaders if they are to improve the fortunes of struggling places.

Leave a comment

Be the first to add a comment.