03How can cities make transport work for them?

Local regulation of bus services for all transport authorities

Challenge: Buses are the main means of public transport in all cities, but local government cannot ensure that bus companies meet local economic, social and environmental needs.

Since the privatisation of buses in 1985, much of bus service quality, routes and pricing has been in the hands of private companies. This means that, while private sector competition is good in many cases, it also creates challenges for bus services, which must meet a wide range of needs of local people and communities.

Ensuring quality of bus services is difficult in cities. People are most likely to use buses if they provide a safe, clean and prompt service, and cities need more people across a wider range of incomes to use buses if they are going to continue to thrive in cities. Local government can use Quality Contract Schemes (QCSs) to ensure private bus companies meet certain quality standards, but they are incredibly difficult to implement and are yet to be used.24 In Tyne and Wear, Nexus is going through a difficult process to implement a QCS which began in December 2011 and is yet to be finished.25

Private bus companies are not incentivised to provide services that meet wider economic and social needs. Subsidies account for around 45 per cent of all bus operators’ revenues.26 The Bus Services Operator Grant (BSOG) funds bus companies on the basis of the miles they travel rather than the number of riders or rider-miles, the true measure of success. The companies receive a bonus for electronic ticketing or having tracking systems for real-time information, which are both good aims. But they have failed to ensure take up in many cities that need them.

Because local government cannot set fares, they cannot ensure affordability or that profits are reinvested into quality bus services. Bus operators are largely free to set fares.27 According to the local bus fares index, fares across the whole of England increased by 270 per cent between 1986/87 and 2011. In London, where fares are regulated, the increase over the same period was 203 per cent.28

Because cities cannot regulate buses or fares, Oyster-style smart ticketing often cannot deliver the same simplicity and ease for users. Oyster-style integrated ticketing offers the best service for residents, workers and businesses, and it can increase bus ridership, passenger satisfaction, boarding speeds and bus revenue.29 Despite its benefits, lack of regulation of buses has led to minimal uptake of Oyster-style integrated ticketing outside of London. Merseytravel, serving Liverpool and surrounding areas, has taken years to implement its integrated ticketing system, the Walrus card, due to the complexities of working across the different systems of bus providers. Integrated ticketing could become a norm if more cities had the power to regulate buses. The benefits of regulation clearly outweigh the costs of competition.

Delivering change: Whitehall should give cities the power to directly regulate bus services to ensure quality buses and the roll of out Oyster-style cards

Government should give transport authorities London-style powers over buses. London’s regulation of bus services provides an overall more efficient service. Single management of the bus system and bus subsidy means that TfL can ensure quality of buses and bus services. Services and fares are specified by TfL and passenger revenues are kept for reinvestment in services – private operators are involved, potentially retaining some market incentives, but they bid for contracts on TfL’s terms.30 TfL also specifies destination displays, capacities and layouts for its buses and has acted to ensure all London buses keep the city’s distinctive red colour.31

Box 3: Regulation for better bus services in Helsinki

Cities with more control over their bus services have been able to ensure better quality services. The provision of public transport in the Helsinki city region falls under Helsinki Region Transport (HSL) with almost 300 bus routes across the city region. Buses were the most popular mode of transport in 2012 (over half of total journeys), and over 80 percent of passengers reported being satisfied with the service.32

HSL joins together seven regional municipalities, and its responsibilities include coordinating the transport strategy across the region, setting fare prices and procuring bus and other public transport services through competitive tenders. These powers have enabled HSL to:

- Coordinate and set timetables

- Integrate the planning of bus services with other modes of transport

- Introduce a unified ticketing system

- Align bus services with the region’s plans to cut carbon emissions – HSL is encouraging operators to reduce emissions by offering financial bonuses, and 45 per cent of the buses operating in the city region are low emission vehicles.

Regulation of bus contracts enabled TfL to implement the widely used Oyster card for payment. Usage of smart ticketing in the form of Oyster cards, travelcards and contactless payment has become so normalised that only 1 per cent of payments are now made with cash, down from 20 per cent in 2003. This has prompted a decision to scrap cash fares on buses altogether in 2014, which will save £24 million a year.33

Box 4: Benefits of Smart Ticketing

Booz & Co, with the Passenger Transport Executive Group (Pteg), identified a number of benefits of integrated smart tickets that extend beyond transport. These included:

- People shifting from other modes of transport to buses, relieving congestion on those modes

- Social benefits, such as saving people time and improved transport satisfaction

- Wider contribution to city life and identity

- Gathering data on passenger behaviour, which can improve capacity and network planning.

Delivering change: In the meantime, cities should improve bus services, quality, fares and smart ticketing through their other powers over parking, planning and procurement.

Nottingham has provided better buses and services by working with bus companies and using other powers at their disposal. Working within the current system, Nottingham leads the way for local government in ensuring quality bus services by using related powers.

The key lesson cities can take from Nottingham is that they can flex their existing powers to improve bus services within the current system. Establishing a system that leverages powers over bus stops, timetables and routes, Nottingham has improved bus quality and services.

Nottingham uses its strengths as a city to make buses work for workers and residents. The City Council recognises that buses are a means to meet a wide range of needs, In turn, they have:

- Ensured that buses support students in both route and cost,

- Made sure most bus routes pass through the city centre,

- Used buses to reduce congestion,

- Used discounted ticketing to make buses affordable and attractive options for transport,

- Leveraged planning measures to focus developments in the city centre or on major bus routes.

Nottingham established a Statutory Quality Partnership Scheme (SQPS) which can regulate access standards, bus stop usage in the city centre and CO2 emissions. Though the process of establishing such a scheme is challenging, it provides tangible benefits for bus users and the wider city transport system. Only bus services that meet the quality specifications of the SQPS can use the bus stops in the city centre. This system works because the City Council can demonstrate that the public benefits of the SQPS outweigh any restriction on competition.

Through controls over bus stops, the City Council gives priority bus parking to members of the SQPS. In exchange, members of the scheme must meet specified standards for green buses and timetables, for example. Members of the scheme also benefit from the City Council managing the bus slot booking system, real-time arrival displays at bus stops and even marshals to help reduce pedestrian disruption to bus timetables.34

Some cities have ticketing schemes that work across operators, but the introduction of an Oyster-style travelcard in Nottingham has been especially successful. The Kangaroo ticketing scheme works alongside individual bus operator ticketing systems to provide easy ticketing for bus, trains, trams and cycling in Greater Nottingham. The Kangaroo card was set up as a voluntary scheme, but it is now effectively statutory as a part of the SQPS and is operated on behalf of the Council. One reason the card has worked so well is because the main bus operators work with the same ticket supplier, making negotiations and implementation easier.

However, without statutory regulatory power like TfL holds, cities have an uphill battle to make buses work for them. Despite its accomplishments, Nottingham City Council faces many of the same challenges as other cities. Each bus operator has their own smart ticket, and the Kangaroo tickets are subject to a fare premium from operators who require a fee in exchange for passengers’ ability to use the card on any bus. This adds additional costs, compared to the regulated smart ticketing system in London.

Long-term funding settlements

Government offers annual funding settlements to local government for transport, which makes funding transport projects riskier, more difficult and more expensive.

Annual funding makes it very difficult for transport to attract other investment. New housing or business parks are often paid for through a mix of funds, both private and public, which need certainty that local government has the resources at its disposal. Without a long-term commitment of funds, local government is constrained in its ability to offer that certainty to private investors. And when councils accumulate capital reserves for these projects, they are often criticised by the Government for building up funds during austerity.

Annual settlements hold back planning for transport projects. Up to 40 per cent of capital projects’ costs are in the planning and design stages which have to be absorbed by the council if a project does not come forward. This presents a huge risk for local government schemes, as councils facing overall budget cuts will be less likely to pay up-front costs for planning projects. In turn, a lack of viable and certain transport investment has wider impacts on the ability of planning departments to bring forward housing developments, schools, and so forth.

Transport funding uncertainty has held back councils from unlocking major strategic sites. For example:

- The Aire Valley Regeneration Project, Leeds: Until it was designated an Enterprise Zone, lack of funding certainty for transport held back the redevelopment of a former industrial area south east of Leeds city centre. To ensure accessibility, the project requires new transport links including the Skelton Grange Bridge, £55 million worth of public transport improvements, new footbridges and cycle paths and the East Leeds Link Road (ELLR).35

- Birmingham, West Midlands: Birmingham’s Local Transport Implementation Plan lays out a strategy for developments across the region. But these plans were stunted due to funding uncertainty around the timing of the 2010 Spending review and from several government funding programmes including the Local Sustainable Transport Fund.36

- Barking Riverside, London: The construction of 10,800 homes requires either an extension of the London Overground or the Docklands Light Railway. Only 1,000 houses have since been built since 2007 as a result of the lack of transport infrastructure. Currently, bus journeys to Dagenham town centre can take 30 to 45 minutes, while an Overground extension could reduce travel times to as little as six minutes.37

To help boost the economy, government wants shovel-ready schemes, but these are very difficult to develop without funding certainty and revenue funding to plan for these projects in the long-term. Local leaders have criticised central government’s recent focus on short-term projects, as this means LEPs must prove projects are deliverable within a year to receive funding, but without the funding certainty to plan for these projects. This is to the detriment of longer-term projects that will strengthen local economies in the long run.38

Box 5: Long-term funding for projects can support the transportation industry

Funding for transport services needs more certainty. Long-term funding for local transport services like bus services, road maintenance and cycling can benefit from long-term settlements as the strategies and programmes for delivering these services spans many years. Recent cuts in bus services are having a negative impact on cities,39 and longer-term settlements would give cities better ways to manage cuts from central government. Also, for cities planning to link in to the future High Speed 2 network, longer-term funding is needed to make sure that bus, road and cycle services meet the needs of the rail passengers.40

Delivering change: Government should offer minimum five-year capital funding settlements for local government

Government can learn lessons from other cities about the strategy for, and benefits of, long-term transport funding settlements for cities. The funding arrangements between the French Government and cities, especially Paris, demonstrate how funding certainty opens up investment in transport that unlocks growth and creates jobs across the city.

Box 6: Central government support for local transport in France

In France, the central government supports local transport investment with longer-term funding settlements. Every city with 100,000 or more people must have a ten-year transport plan. There is significant national investment in five-year allocations with ten-year strategies. Compare this to the UK where cities are good at the strategies and visions but cannot secure funding to realise them. The long-term funding settlement provided more certainty for other investors including institutions and for taxpayers who part-funded the work. Increased certainty reduces costs in the planning stages and can often reduce the interest payments.

Paris recently received a long-term funding settlement for major rail investment. In March 2013, the French Government committed over £20 billion in long-term funding for the construction of the New Grand Paris transportation project. By 2030, New Grand Paris is expected to add 205 km of new metro lines to the region (mainly on the outskirts of the city), open 72 new metro stations and upgrade existing metro routes. It is expected to increase transport capacity, bring down the average commute per user from 24 to 17 minutes and create 15,000 new jobs per year.41

Some progress is being made in the UK, as government has made a recent move to five-year indicative funding settlements, but more can be done. Through the City Deals process, four LEPs will receive ten-year funding settlements for major transport schemes. Building on this approach, the Treasury needs to work with the Department for Communities and Local Government (DCLG), the Department for Business, Innovation & Skills (BIS), DfT, the Highways Agency and Network Rail to develop a longer-term funding package for local projects that makes the most of larger national priority projects. Otherwise, cities will not be able to make the enabling transport investment to make the most of the Northern Hub or HS2.

Local funding for local transport

Challenge: Cities cannot sufficiently raise revenues for local transport projects residents and businesses need.

Councils are overly dependent on central government funding sources for local transport projects. Central government control of funding also limits local authorities’ ability to raise money for transport projects, reduces transport investment and limits what councils can do.

Overly-centralised funding for transport is also more risky. Because central government is the major funder of local transport projects, they also carry most of the risk on the project. If a project falls through or costs rise, the burden largely falls on Whitehall. Because the risk is higher, central government is likely to fund fewer schemes or provides less funding for each project it supports. Risk is also higher for central government because they know less about the local economy and transport system. Because Whitehall cannot have the same relationships and local knowledge that councils do, they regard local schemes to be riskier than a council would, increasing cost and decreasing investment.

The limited financial tools cities have are not practical in many places. For example, business rates supplements are not viable in many cities outside London, as business rates have been burdensome for many firms. The same can be said for the Community Infrastructure Levy (CIL).

Local funding for local projects means people pay for the transport that they benefit from. Some element of central funding is usually necessary for transport projects. Any major transport scheme will have local, city-wide, regional and some national benefits, and funding for projects should reflect this. Because the vast majority of benefits from new transport go to local residents and businesses through reduced congestion, alternative modes of travel, fewer emissions or access to new homes or jobs, local residents and businesses should pay a higher proportion of the investment.

Local taxes and fees for transport projects align the costs, risks and benefits of investment with the businesses and residents in the area.

As Box 7 shows there are a range of local taxes, fees and charges for funding local transport projects that have been implemented by cities in the UK and abroad to bring in more transport investment that meets the needs of local people and businesses. These examples can be adapted to the particular transport investment requirements and needs or strengths of a city’s economy.

Box 7: Local taxes, fees and charges to fund transport projects

Tax Increment Finance (TIF)

TIF involves reinvesting a proportion of future business rates from an area into infrastructure today, making it possible to unlock regeneration projects without the need for additional taxation.42 However, TIF has not been used in England outside of Enterprise Zones due to complications in the business rates tax system.

TIF is being used in the London’s Northern Line Extension to the Enterprise Zone in Nine Elms.43 The development project will include 16,000 homes, office and retail space, and could create up to 25,000 jobs by 2026.44 Scottish cities can negotiate TIF schemes with the Scottish Government. Falkirk has a £67 million TIF scheme which is currently in construction. Through improvements to the M9 motorway links and Grangemouth flood defences, it is estimated that the scheme will unlock over £400 million in private investment and create almost 6,000 jobs.45

Milton Keynes’ Urban Development Area tariff

In 2007, Milton Keynes applied an Urban Development Area tariff, which is a fixed amount payable by owners of land located in areas where new developments are most likely to take place. The tariff aims to support new infrastructure needed for those areas including roads, health facilities and schools. It is estimated the tariff will raise almost 20 per cent of the city’s £1.6 billion infrastructure costs for the decade ahead.46

Paris’s employer tax

The regional transport authority mainly relies on the employer transport tax to fund transport investment.47 This approach levies a public transport tax on employers whereby a sum is collected from employees’ salaries, depending on the location of the business. The tax is targeted, with higher rates in more affluent areas, and excludes start-up firms and small shops. In 2012, almost 40 per cent of the region’s £6.7 billion public transport budget came from the transport tax.48

Denver’s local sales tax

Due to its ability to raise local taxes, Denver Metropolitan region is undertaking a £2.5 billion train extension project called Fastracks. The project is mainly funded by a voter-approved 0.4 per cent sales tax increase passed in 2004. Fastracks will add six new lines with 57 stations, improve existing lines and add 18 miles of new suburb-to-suburb routes.

Durham’s congestion charging

In Durham, congestion charging has decreased traffic, increased bus usage and improved safety. The charges have generated enough income to subsidise an enhanced bus service that goes to and from the charging area and to support a Shopmobility scheme that increases mobility for the disabled.49

Nottingham’s Workplace Parking Levy

The Workplace Parking Levy is a congestion charging scheme where a charge is placed on employers who provide parking. Employers must licence their workplace parking and pay the charge if they provide more than 11 parking spaces. In addition to discouraging car use, the scheme also boosts funding for local transport. The money raised helps fund Nottingham’s tram system, railway station and Link bus network.

Delivering change: Local government should set fares and fees as well as democratically voted, hypothecated tolls and taxes that support investment in their transport systems. This aligns the costs of investment with those who benefit.

When cities are able to levy local taxes or set fees to invest in local transport projects, it benefits the wider transport system and the economy. Taxes and fees, when responsive to local transport needs, can raise money to make projects viable and align the costs of transport with those who benefit from it.

Single management of transport systems: helping people commute across the city region

Challenge: Funding for transport investment and services is too fractured, holding back investment and reducing quality.

Under the current system, transport planning and funding do not align with how people use transport services. If the way that local and central government think about, plan for and invest in transport doesn’t match how people use it, the transport system will not serve people or the economy the best it can. This is for two mains reasons.

First, transport planning covers the wrong geography.

Sometimes the scale is too small. Outside the Integrated Transport Authorities (ITAs) that exist in the former metropolitan county areas, coordination of transport strategy largely falls to unitary authorities and county councils. This means the way government pays for and plans roads, buses and rail very often doesn’t reflect how people actually use it, unless local authorities proactively work together to increase coordination.

In other instances, boundaries may be too splintered and complicated. For example, in Birmingham, three LEPs work with the West Midlands Passenger Transport Executive (Centro). This creates incentives for councils and LEPs to compete for funding and avoid sharing information, rather than encouraging them to collaborate and coordinate. Priorities are set by the LEPs for Centro to deliver, leaving Centro to weigh up and balance resources in developing schemes across each of the LEP areas to attract funding.

National transport projects tend not to coordinate with local transport systems. Highways Agency and Network Rail are national transport bodies managing large-scale and long-distance transport, but they lack incentives and capacity to coordinate those major road and rail projects with cities.

Second, funding pots for transport are fractured and uncoordinated. Funding for transport is split by different modes, geographies and timelines, which makes it harder to coordinate investment across cities.50

Local authorities, LEPs, the Highways Agency, Network Rail and private bus companies share control over city transport systems, but their funding and the strategies used to allocate it are not coordinated effectively. A non-exhaustive list of other DfT funds includes a funding settlement with TfL, funds for pothole repairs in England, local capital block funding, Better Bus Areas, Pinch Point Funding, Local Sustainable Transport Fund, Green Bus Fund, Emergency Funding, Private Finance Initiative, Exceptional Maintenance, the Community Infrastructure Fund, Concessionary fares, Bus Funding and Cycling and Walking funds.51

It is not the existence of different funding streams that is the challenge, per se, but the complexity and complications for coordinating them into one transport system for a city region. The fixed funding and management boundaries between these different streams prevent flexible decision-making and coordination across the different areas they are each earmarked for, which will often be interrelated in practice.

Delivering change: More cities need ITAs, and ITAs should be bolstered with more powers

ITAs are cross-boundary bodies with responsibility and control for the transport investment and management process. ITAs overcome many of the geographic coverage and funding problems for transport because they:

- Cover a city region geography, coordinating across local authorities

- Bring together investment and strategies for various modes of transport

- Provide a high-level body to coordinate with Highways Agency and Network Rail

- This is not about creating a new body or institution; rather it is about bringing together existing organisations and funding to use them in a more strategic way.

Birmingham and the other West Midlands authorities are planning to establish a new Integrated Transport Authority (ITA) which will aim to improve coordination in the city region and increase cooperation between the three local LEPs. The new ITA will consist of the leaders of the seven local councils and will be mainly responsible for developing a coherent overall strategy across the city region coordinating project delivery with Centro (the Passenger Transport Executive) and local authorities. In addition to coordinating strategies across the three LEPs, the new ITA will coordinate all modes of transport and bring the LEPs into the decision-making process, particularly around strategy setting.52

The GMCA coordinates transport at the city region level. Greater Manchester Combined Authority (GMCA) was the first combined authority established in the UK. The combined authority incorporated the powers of the ITA with the regional governance body. GMCA, Transport for Greater Manchester (TfGM), which acts on behalf of GMCA, and the ten local authorities in Greater Manchester are governed by a clear division of roles that enables GMCA and TfGM to manage strategic transport matters for the city region.53 It operates as a city region authority but draws its resources from the ten councils, and 64 per cent of TfGM revenue funds come from a levy on the ten authorities. It also controls the Metrolink system farebox, which GMCA has used to support prudential borrowing that underpins half of the current £1.5 billion Greater Manchester Transport Fund (GMTF). Importantly, GMTF prioritises projects based on its ability to secure wider economic, environmental and social returns than are captured by traditional transport appraisal.

Greater Manchester has developed good relationships with other transport bodies. GMCA and TfGM have worked effectively with Network Rail at an operational level on projects such as the Northern Hub and are now looking to build on this with regard to HS2. The Greater Manchester partners have also benefited from a long-standing stake in Manchester Airport, which has enabled planners to join up the airport with other transport modes within city region transport strategies. Some early steps have been taken to coordinate highways activities in Greater Manchester, including GMCA providing the urban traffic control signals function for the Highways Agency and ten highways authorities through GM Urban Traffic Control, which runs the second largest traffic signal network outside of London.54 However, GMCA leaders feel more still needs to be done at city level. This is highlighted in the Greater Manchester Growth and Reform Plan (SEP) submission to the Local Growth Fund, which proposes highways, rail and bus market reform policies alongside a forward investment programme.

Greater Manchester’s success provides a strong rationale both for local authorities to pass powers upwards to a combined authority or ITA and for central government to grant transport funding and coordination powers to ITAs.

Integrating transport into the wider growth agenda

Challenge: Disjointed transport systems that don’t operate in a way that responds to people’s day-to-day needs.

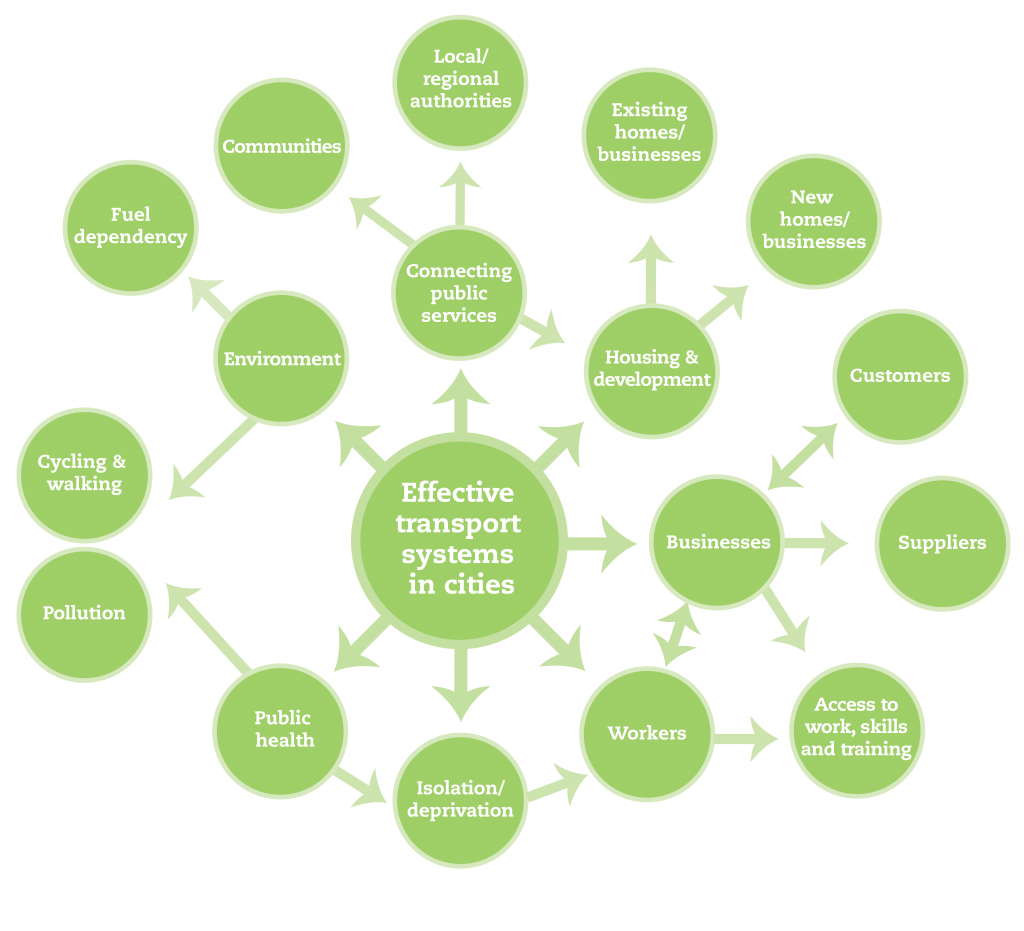

Both central and local government tend to treat transport and infrastructure in its own silo. But investment in transport, or lack thereof, has an impact on the wider economy. Car dependency has changed the way cities are planned — with many developments being organised around roads — which has an effect on how people get to or are able to find jobs. One small part of transport, the use of cars, thus has wide ranging impacts across the local economy. Figure 3 below demonstrates the wide reach that transport has in local economies.

Figure 3: The knock-on effects of cuts to transport spending across different government departments and the impacts on growth

LEPs lack a means to gauge the costs, benefits and growth generation from transport projects as opposed to the benefits of other types of investment. When they take control of major transport investment in the Single Local Growth Fund (SLGF) from 2015/16, LEPs will have a responsibility for deciding the trade-offs between transport, housing, schools and other big investments in the area.

Concerns have been raised that the DfT is contributing at least £200 million of funding to this pot, but the economic and social value of transport may be overlooked by individual LEPs. The Eddington study noted that traditional cost-benefit analysis (CBA) does not take adequate account of all the benefits of transport projects, such as reduced congestion and any potential environmental benefits.55

Delivering change: Coordinating transport policy and funding across government functions using combined authorities and joint teams at the local and national levels.

Transport strategy and funding should take into account the wider impacts on housing, regeneration and jobs. Building on the coordination discussed in Section 3.4, the West Midlands and Manchester have not only linked-up their different modes of transport, but they also link transport with other policy areas.

Many examples exist within the current system where councils have joined up transport with their other objectives to make them work for each other.

Connecting transport and jobs

Through the Workwise Programme in Birmingham, Centro has helped 14,000 Jobcentre Plus customers overcome transport barriers and get back to work. Funded by the Government’s Local Sustainable Transport Fund, Workwise offers long-term unemployed people unlimited day passes to attend interviews or training and up to eight weeks of free travel passes once they start work.56 Additional support includes advice on journey planning, information on sustainable modes of travel and a cycling option whereby jobseekers are offered a free recycled bicycle, safety accessories and other complementary support.

The Nottingham ‘Jobseeker Citycard’ scheme has helped cardholders find jobs by making travel to interviews, Jobcentre appointments and work easier. Jobseeker Citycards allow holders who are either job-seeking or in the first four weeks of a new job to access:

- Half-priced day travel tickets

- Subsidised bike hire

- Access to personalised travel information.

Connecting transport with environmental and health objectives

In Bristol, cycling is used more widely than in other UK cities – over six per cent cycle.57 One reason for this is that cycling is part of a broader programme to reduce congestion, reduce pollution and improve health, tackling multiple challenges through a targeted, cross-cutting approach. Bristol is the Green Capital of Europe 2015 and became Britain’s first designated ‘Cycling City’ in 2008.58 Bristol City Council has noted the health benefits of cycling and advised that infrastructure, behavioural change and ‘bikeability’ (cycle training) were key for promoting cycling.59

Connecting transport to housing can bring forward more homes

London’s Metropolitan Railway (today the Metropolitan Line of the London Underground) gave rise to what was known as ‘Metroland’ when it was first built in the early 20th century, a set of growing suburbs in the north-west of the city that grew along the route. These suburbs grew out of the need for more housing for the capital’s booming population and normalised commuting into central London. Housing estates were developed in the early 1900s at Wembley Park and at Cecil Park in Pinner on land next to the railway lines, in order to boost the usage of the line.

Integrating transport into economic development

The Greater Manchester Combined Authority shows how better coordination frees the city from the narrow constraints of traditional transport appraisals and enables better integration of transport within local growth priorities. Manchester has opened up new investment opportunities – beyond what national transport appraisals would offer – that meet the needs of their local economy.

Local government and LEPs need a cross-cutting measure to compare and prioritise investments. The Single Local Growth Fund is a major new responsibility for LEPs, who will now have to prioritise transport projects in conjunction with other big schemes in housing, schools and energy, for example. Past investment patterns have been criticised for either being arbitrary or too heavily based on narrow cost-benefit analyses (CBA), which focus on economic efficiency and can exclude broader goals, such as encouraging economic growth.

Delivering change: LEPs can use a cross-cutting strategy for investing in transport in the Single Local Growth Fund.

The forecasting, modelling and appraisal frameworks for transport investment should be independently reviewed so as to take account of the wider economic impacts and links between transport, land use and economic development.

In the meantime, Multi-criteria analysis (MCA) is one option for LEPs, because it allows decision-makers to rank projects against multiple objectives and reflect local priorities.60 MCA can help account for the impact of transport infrastructure on “(1) costs; (2) convenience; (3) environmental aspects; (4) strategic factors; (5) political factors and national prestige; (6) alignment with policy goals and objectives; and (7) income distribution considerations”.60 MCA is not new to the UK, as it has been used by UK government agencies to guide investment in highways, for example, taking into account considerations such the cost of construction, travel time saved, reductions in accidents and social and environmental effects.62

Figure 8: Weighing the benefits of transport within other economic priorities

In Canada, cities such as Calgary have developed a data-led qualitative and strategic model to consider the overall impact of transport projects on economic competitiveness. This has helped city leaders decide whether they should invest in social infrastructure (housing, community centres) or ‘hard’ infrastructure such as roads.63 Accordingly, LEPs and combined authorities could use this approach for a more structured, coordinated and holistic approach to decision-making.